- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Microplastic Pollutants

About this book

Microplastic Pollutants introduces the reader to the growing problem of microplastic pollution in the aquatic environment and is the first ever book dedicated exclusively to the subject of microplastics. Importantly, this timely full-colour illustrated multidisciplinary book highlights the very recent realization that microplastics may transport toxic chemicals into food chains around the world.

Microplastic pollutants is currently an important topic in both industry and academia, as well as among legislative bodies, and research in this area is gaining considerable attention from both the worldwide media and scientific community on a rapidly increasing scale.

Ultimately, this book provides an excellent source of reference and information on microplastics for scientists, engineers, students, industry, policy makers and citizens alike.

- A detailed chronological history of plastic materials from their creation until the present day

- Extensive review and discussion of the existing literature on the interactions of microplastics with chemical pollutants and their effects on aquatic life

- Explanation and provision of the techniques used for the detection, separation and identification of microplastics

- Detailed multidisciplinary information on the way in which plastic materials and microplastics behave in the aquatic environment

- The provision of extensive multidisciplinary reference data relating to plastic materials and microplastics

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Microplastic Pollutants by Christopher Blair Crawford,Brian Quinn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Environmental Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The emergence of plastics

Abstract

The first chapter of this book introduces the reader to the world of plastics and explains the way in which these materials rapidly began to change our world. With considerable detail, the early history of plastics is discussed in chronological order from the humble beginnings of the first semi-synthetic polymer to the mass production of plastics at the end of the Second World War. As an era characterised by considerable innovation, as well as, bitter rivalry and patent disputes, a historical account is given of the plastic pioneers who lead the way in the development of these remarkably versatile materials which, ultimately, became a fundamental part of our modern society.

Keywords

Bakelite; Casein; Celluloid; Cellulose; Cellulose nitrate; Development; Dispute; Early history; Fibres; First World War; Fluoropolymer; History; Innovation; Invention; Lacquer; Manufacture; Monomer; Natural rubber; Neoprene; Nitrocellulose; Nylon; Parkesine; Past; Patent; Perspex; Plastic; Poly; Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMA); Polyacrylonitrile (PAN); Polyamide (PA); Polychloroprene (CR); Polyester; Polyethylene terephthalate (PET); Polymer; Polymerization; Polyoxymethylene (POM); Polystyrene; Polytetrafluorethylene (PTFE); Polyurethane (PU); Polyvinyl chloride (PVC); Production; Rubber; Second World War; Vulcanization; Vulcanized

Introduction

Since the dawn of the modern human race, and throughout our 200,000-year history, never before has the world seen materials like plastics. Indeed, plastics are such a new phenomenon in this world, that to date, practically no biological organism in the environment has sufficiently evolved to readily consume them. For this reason, plastics represent an unprecedented turning-point, not only in our own evolutionary history, but in the evolutionary history of the Earth. These remarkable, versatile and yet ubiquitous substances have fundamentally changed how we live and revolutionised the modern world. Unfortunately, these same substances which have allowed us to make great leaps and technological advancements may ultimately lead to significant environmental problems in the near future. Unless we are able to develop new technologies, processes or approaches to deal with the persistence of plastics in the environment, we will continue to observe increasing accumulations of these somewhat everlasting substances. But what about biodegradable plastics, you might ask? Indeed, fairly recent advancements have resulted in the creation of plastics produced from natural substances, such as soybeans and corn starch, which can be biologically broken down. However, most plastics in use today are simply not biodegradable and are in fact, highly resistant to degradation. Indeed, the billions of tonnes of plastics already released into the environment, since the origin of their creation, remain with us to the present day in one form or another and may take thousands of years to completely degrade.

Remarkably, the persistence of plastic and its effects on the aquatic environment were demonstrated in 2005, when a single piece of white plastic was found among numerous other pieces of plastic recovered from the stomach of a Laysan Albatross chick carcass. It is likely that the bird died due to starvation from consistently ingesting plastic, which has no nutritional content and can cause intestinal blockages. Examination of the piece of white plastic revealed that it was imprinted with a serial number. Cross-checking and verification of that number revealed that, astonishingly, the plastic had originated from an American Navy seaplane which was shot down thousands of miles away near Japan in 1944 during the Second World War. Subsequent computational modelling and simulations revealed that the piece of plastic had undergone a 60-year odyssey within the North Pacific subtropical oceanic gyre. Bounded by the gyre are two distinct swirling vortices of plastic garbage. One vortex is situated off the coast of Japan and is termed the Western Garbage Patch. The other vortex is situated off the coast of America and is termed the Eastern Garbage Patch. Together, these two patches form the Great Pacific garbage patch, a colossal swirling area of significant plastic accumulation (see Chapter 3). Amazingly, it was calculated that the piece of plastic from the seaplane had spent approximately 10 years travelling around the Western Garbage Patch. Eventually it escaped from this vortex and was carried thousands of miles by the North Pacific Gyre to the Eastern Garbage Patch. It then spent the next 50 years circling around this region, until it was eventually eaten by a Laysan Albatross chick in 2005. The carcass of that bird was then discovered by researchers at Midway Atoll, a Hawaiian Island in the middle of the North Pacific Ocean. Importantly, since the plastic was still intact, had it not have been collected by the researchers then it would have been freely available to be consumed again by another organism, after which this deadly cycle of plastic ingestion could potentially be repeated for thousands of years.

Thus, although plastics could quite rightly be considered as one of our greatest ever achievements, and the pinnacle of technological innovation, unfortunately plastics are also increasingly becoming recognised as representing one of the greatest environmental challenges that our species has ever known. In the face of their groundbreaking versatility and contemporary marvel, plastic litter has profoundly negative consequences. In this book, we shall explore in great detail, the way in which plastics behave in the environment and their effects upon the natural world. However, before we do so, it is important to examine the remarkable history of the development of these materials in order that we can appreciate precisely what plastics are and how this diverse class of unique materials gradually became intertwined within our modern lives to form a fundamental part of our contemporary society.

What are plastics?

The term ‘plastic’ first appeared in the 1630s in which it was used to describe a substance that could be moulded or shaped. The term derives from the Ancient Greek term plastikos, which refers to something that is suitable for moulding, and the Latin term plasticus which pertains to moulding or shaping. The modern use of the term plastic was first coined by Leo Hendrick baekeland in 1909 and today, plastic is a generic term used to describe a vast array of materials. But what do we mean when we talk about plastics, and what exactly are these strange and yet familiar substances?

As an integral part of our daily lives, we tend to use the word plastic on a regular basis without paying much attention to what plastics actually are. From plastic bags and writing pens to pipes and electrical equipment, different types of plastic are everywhere. However, they all have something in common; all plastic substances are composed of large chain-like molecules, termed macromolecules. These large molecules are composed of many recurring smaller molecules connected together in a sequence. We term a substance with this kind of molecular arrangement as a ‘polymer’. The existence of macromolecules, and their characterisation as polymers, was first demonstrated by German chemist Hermann Staudinger in the 1920s. Thereafter, he formed the first polymer journal in 1940 and received the Noble Prize in Chemistry in 1953. Parenthetically, the word polymer is a combination of the Ancient Greek words poly (meaning many) and meres (meaning parts). Each individual molecule in a polymer chain is considered to be a single unit and we call each of these a ‘monomer’. In this case, the prefix ‘mono’ is used to mean single. Thus, monomers are small molecules that have the ability to bond together to form long chains. We can visualise these large chains by thinking about a polymer as being akin to a pearl necklace. If we can imagine the entire necklace to be the polymer, then each individual pearl would be considered as a monomer (Fig. 1.1).

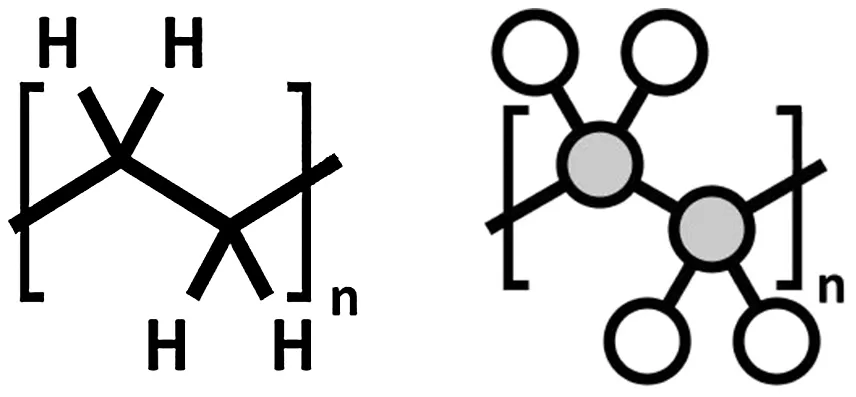

The process of connecting monomers together to form a polymer is called ‘polymerisation’. In Fig. 1.2, we have the monomer ethylene. When ethylene is polymerised, it forms the common plastic polyethylene (Fig. 1.3). These large molecular chains can then be moulded and shaped to form solid objects. In Fig. 1.4, we can see that a polyethylene bag is actually composed of an amorphous mass of tangled branched polymer chains. Each of these chains is, in turn, composed of many repeating ethylene monomers.

Figure 1.1 Small molecules (monomers) connect together in a repeating sequence (polymerise) to form a large chain-like molecule (polymer).

Figure 1.2 Ethylene (monomer).

Figure 1.3 Polyethylene (polymer).

Figure 1.4 A polyethylene bag is composed of a mass of large polymer chains, which are in turn composed of many repeating ethylene monomers.

Thus, all plastics are polymers, and polymers are simply long chains of many repeating monomers. Typically, in commercial plastics, there will be between 10,000 and 100,000,000 monomers per chain, depending on the type of plastic. Often, each monomer of a polymer is the same as the next monomer in the sequence and this is termed as a ‘homopolymer’. However, some polymers are composed of different alternating monomers, and this is termed as a ‘copolymer’. In other cases, polymers can be composed of branched chains in a variety of architectures, thus exhibiting a deviation from a simple linear polymer chain. Furthermore, two polymers can be mixed together to form a plastic blend that simultaneously displays the characteristics of each individual polymer, thereby providing the benefits of both. Alternatively, mixing of two polymers may form a blend with enhanced properties, in comparison to each individual polymer. Accordingly, we shall explore the properties and characteristics of plastics in more detail within Chapter 4. The vast majority of polymers in today’s world are the synthetic plastics created by humans. However, there are also many natural polymers in existence. For example, our DNA is a polysaccharide, composed of many repeating sugar units (monosaccharides). Similarly, our hair is a polypeptide protein filament which is composed of long chains of amino acids, connected together by peptide bonds. Thus, it is important to note that although all plastics are polymers, not all polymers are plastics.

The advent of plastics

The exact point at which plastic entered our world has no fixed point in time and rather, we should think of the generic term ‘plastic’ as referring to a large assortment of different polymers created as a result of our attempts to improve upon the raw materials provided by nature. Consequently, the advent of plastics is quite indistinct, and indeed, one could contend that the start of our path to a plastic society first began with the creation of rubber balls by the Mesoamericans around 1600 BC or perhaps with the introduction of natural rubber by French explorer Charles Marie de La Condamine in 1736. Incidentally, while on an expedition in South America, tensions within the expedition group resulted in La Condamine breaking off from the others and travelling alone to Ecuador. Along the way, he stumbled across the Pará rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis) in 1736. Later that year, La Condamine brought samples of this natural rubber back to France where he subsequently studied the substance and presented a scientific paper purporting the beneficial properties of natural rubber in 1751.

Alternatively, perhaps the Grandfathers of plastic are British manufacturing engineer Thomas Hancock, who patented the vulcanization of natural rubber in 1843 in the United Kingdom, and American chemist Charles Goodyear, who patented vulcanization of natural rubber in the United States 8 weeks later in 1844. Considerable controversy ensues as to who was the true inventor of the vulcanization process, and indeed a lengthy and bitter court battle ensued when Goodyear attempted to patent the vulcanization process in the United Kingdom. Ultimately, to Goodyear’s dismay, the judge ruled in favour of Hancock. Nonetheless, both men are considered as rubber pioneers who made significant contributions to the development of vulcanized rubber. In the case of Hancock, the process was discovered after many years of experimenting with natural rubber and sulphur. In the case of Goodyear, the process was discovered as a result of many years spent trying to improve the characteristics of natural rubber. Goodyear recognised that natural rubber had an inherent problem due to its unstable thermal characteristics. In the heat, natural rubber has a tendency to melt and become sticky, producing a particularly pungent odour in the process. Conversely, in the cold the substance becomes hard and brittle. In his attempts to address this problem, Goodyear became obsessed with trying to improve the properties of natural rubber. He subsequently mixed the substance with all manner of things, including turpentine, witch-hazel and even cream cheese. Often struggling with debt from overspending on materials and the complaints of his neighbours regarding the unpleasant odours emanating from his property, Goodyear continued his trial-and-error experiments heedlessly, but nothing appeared to work. Eventually good fortune arose when on one occasion he mixed natural rubber with sulphur and lead carbonate. The exact nature as to what happened next is shrouded in myth and legend. Indeed, one account claims that during an argument with his business partner Nathaniel Hayward, Goodyear threw the rubber onto a hot stove. However, instead of catching fire, they noticed that the rubber charred and became solid. Another account states that Goodyear absentmindedly left the rubber on the stove and later noticed the charring effect. Irrespective of the events surrounding the discovery, experimentation with the mixture over the next few years ultimately resulted in Goodyear perfecting the vulcanization process.

On the other hand, perhaps we could consider that the development of the first fully-synthetic polymeric compound known as Bakelite, by Belgian chemist Leo Hendrick Baekeland in 1907, was the moment that heralded the birth of plastic. Certainly, Bakelite transformed the world at that time with an assortment of new products. Indeed, by the end of the 1930s more than 200,000 tonnes of Bakelite had been made into a vast array of household items. Nevertheless, for the purposes of this book, we shall meet in the middle and consider the starting point of plastic as situated somewhere between the vulcanization of rubber and the creation of the first fully-synthetic polymer. Accordingly, the advent of the plastic age was the development of the first semi-synthetic polymer.

The early history of plastics

1862–98

Our story of plastic begins within the United Kingdom in 1862. That year, the second of the decennial Great International Exhibition was taking place with 6.1 million attendees and 29,000 exhibitors from 36 different countries. The first exhibition had taken place in 1851, with considerable support from Prince Albert, and was heralded as a momentous success. Consequently, the Royal Society of Arts decided upon a second exhibition in 1861. However, delays with the assigned committee, and the outbreak of war amongst France and Austria, resulted in postponement of the second exhibition until 1862. A further setback came with the death of Prince Albert in December 1861, thereby preventing opening of the event by the Queen. Even so, the Queen ensured that everything possible was undertaken to ensure the event was a grand national ceremony. Accordingly, the exhibition went ahead on 1 May 1862 at a 90 square metre site in South Kensington, London. Parenthetically, the same site today houses the Natural History Museum. The exhibitions were organised into 36 classes, ranging from the latest engineering advancements, such as the creation of ice by refrigeration; to the latest scientific advancements, such as the very first safety match. However, amongst all 29,000 exhibits was Exhibit 1112 displaying a peculiar substance termed Parkesine. The substance was created by, and named after, its inventor Alexander Parkes. Parkesine was demonstrated at the exhibition as being a hard but flexible substance capable of being cast, carved and painted. Thus, the substance attracted great attention as being a suitable replace...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- About the Author, Christopher Blair Crawford

- About the Author, Brian Quinn

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The emergence of plastics

- 2. The contemporary history of plastics

- 3. Plastic production, waste and legislation

- 4. Physiochemical properties and degradation

- 5. Microplastics, standardisation and spatial distribution

- 6. The interactions of microplastics and chemical pollutants

- 7. The biological impacts and effects of contaminated microplastics

- 8. Microplastic collection techniques

- 9. Microplastic separation techniques

- 10. Microplastic identification techniques

- References

- Glossary and list of abbreviations

- Index