eBook - ePub

Organic Farming

Global Perspectives and Methods

- 436 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Organic Farming

Global Perspectives and Methods

About this book

Organic Farming: Global Perspectives and Methods explores the core definition and concepts of organic farming in sustainability, its influence on the ecosystem, the significance of seed, soil management, water management, weed management, the significance of microorganisms in organic farming, livestock management, and waste management. The book provides readers with a basic idea of organic farming that presents advancements in the field and insights on the future. Written by a team of global experts, and with the aim of providing a current understanding of organic farming, this resource is valuable for researchers, graduate students, and post-doctoral fellows from academia and research institutions.

- Presents the basic principles of organic farming and sustainable development

- Discusses the role of soil in organic agriculture

- Addresses various strategies in seed processing and seed storing, seed bed preparation, watering of seeds and seed quality improvement

- Includes updated information on organic fertilizers and their preparation techniques

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Organic Farming by Sarath Chandran, Unni M.R., Sabu Thomas, Sarath Chandran,Unni M.R.,Sabu Thomas,Unni M.R in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Agriculture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Contribution of Organic Farming Towards Global Food Security

An Overview

Terence Epule Epule, Department of Geography, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

Abstract

This chapter verifies the contributions of organic and inorganic farming within the context of global food security. This chapter is based on data obtained from a synthesis of existing literature obtained through Google Scholar, the Scientific Citation Index (SCI) database, and ISI Science. The first part of this work explores the conceptual issues around organic and inorganic farming; this is followed by a synthesis of the potential effects of organic and inorganic farming on global food security and finally the effects of organic and inorganic farming on food security in Africa. The results from this synthesis show that organic farming can indeed reduce global food insecurity but there is a limitation to the extent to which this can be obtained as it has been observed that there is a threshold beyond which a combination of organic and inorganic farming options produce the best effects and organic farming alone cannot sustain production. A system dependent on organic farming is rather complex and may warrant that: the current scale of arable production be expanded while the farmers need to be trained on how to valorize the advantages of organic farming especially in Africa. Understanding how to make use of other components of agro-ecology is mandated. The weaknesses of conventional farming must be evaluated in detail by setting up pilot agro-ecology farms and comparing their yields with conventional farms around the world in general and in Africa in particular. Most of the studies consulted recommend either inorganic farming or a combination of inorganic and organic. Therefore, as a way forward, farmers must be given the opportunity to take decisions on which way to go and this should be based on the availability of sufficient information on the economic, social, and environmental sustainability implications of their actions. In addition, the markets for farm inputs should become more competitive and efficient, and this will trigger lower prices and better services to the farmers.

Keywords

Organic farming; inorganic fearming; agro-ecology; conventional crop yields; global

1.1 Introduction

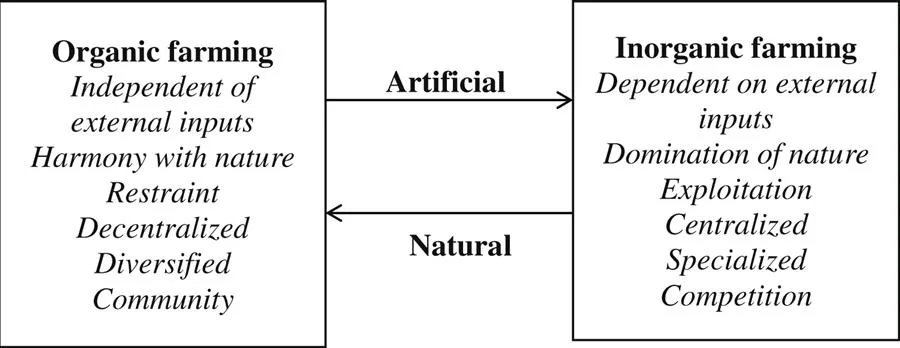

Organic farming can be broadly described as a form of agriculture that relies on components such as green manure, compost, crop rotation, and biological pest control. However, organic farming may also involve the use of fertilizers and pesticides which are obtained from natural sources such as bone meal from animals and pyrethrin from flowers (Badgley et al., 2007; Seufert et al., 2012). The differences between organic farming and inorganic farming are based on the fact that inorganic farming is based on synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and plant growth regulators such as antibiotics and hormones, while organic farming is based on the power of natural inputs or elements (Badgley et al., 2007; Lindell et al., 2010a, b; Seufert et al., 2012). Generally, the major differences between organic and conventional farming are based on some of the following characteristics: decentralization, independence, community, harmony with nature, diversity, and restraint (Fig. 1.1).

Due to increased population pressure on planetary resources, the carrying capacity of the Earth is being reduced and the possibilities of Earth feeding a population of 9 to 10 billion people by 2050 remains very bleak (Badgley et al., 2007). To subvert the current global food production dilemma, global and regional food production systems need to be enhanced to make sure that current and future agricultural systems can feed more people while minimizing the environmental repercussions of food production systems (Seufert et al., 2012).

The fundamental principle of organic farming is geared towards producing more food with the minimum environmental footprints. In spite of the environmental benefits of organic farming, it has also been argued that such systems are often associated with reduced yields when compared to inorganic systems (Seufert et al., 2012). It has been stated that to increase the yields of organic farms to levels that can equal those of inorganic farms, more land could be brought into cultivation; the latter is associated with increased loss of forests, biodiversity degradation, and inadequate organically acceptable farming procedures that can produce sufficient quantities of food without weathering the environmental benefits of organic farming (Trewavas, 2001; Seufert et al., 2012). In Africa, for example, the prospects of increasing fallowing have diminished due to limited land for further expansion of farmland (Morris et al., 2007). However, Badgley et al. (2007: 86) presented a contrary argument to that of Seufert et al. (2012) that organic farms are more productive than conventional farms, “…organic agriculture has the potential to contribute quite substantially to the global food supply, while reducing the detrimental environmental impacts of conventional agriculture.” The latter study has also been criticized by Seufert et al. (2012) on the grounds that: (1) they included organic crop yields from farms having inputs of large amounts of nitrogen from manure; (2) they included less representative low conventional yields in their comparison; (3) they failed to consider yield reductions over time due to rotations with nonfood crops; (4) double counting of high organic yields; and (5) extensive use of unverifiable data from the gray literature.

With the criticisms above, it is difficult to predict if organic farming will be able to render answers to the polemics of providing more food to mankind and minimizing the associated environmental footprints. The Seufert et al. (2012) paper fails to use data points from Africa and, as such, its conclusions cannot be generalized because there are evidently studies on this subject pertaining to Africa; maybe, it is more germane to say there are insufficient studies on this topic regarding Africa.

1.2 Components of Organic and Inorganic Farming

Organic and inorganic farming can be identified as two components within two broad agricultural systems, which are agroecology and dominant/traditional (conventional) approaches, respectively. In most of Europe, North America, and the global south, agricultural production has been based on a traditional dominant agricultural model called conventional agriculture; based on: (1) inorganic fertilizers and hybrid seeds (Matson et al., 1998; Snapp et al., 2010; Epule et al., 2012), (2) commercial crops, market development, and global integration, and (3) mechanization and monoculture. This model has been associated with problems of environmental degradation globally and agricultural production stagnation and a decline in the global south due mainly to problems of poverty and access to external inputs (Rosegrant and Svendsen, 1993; Matson et al., 1997; Hossain and Singh, 2000; Reid et al., 2003; Lindell et al., 2010a, b; Epule et al., 2012). Alternatively, the agroecological approach offers a new way forward. It is based on production that uses natural nutrient cycling with little or no synthetic substances (Badgley et al., 2007; Bezner-Kerr et al., 2007; Snapp et al., 2010). This approach advocates improvements in arable production through four pathways: (1) accumulation of organic matter and nutrient cycling through the use of natural processes; (2) natural control of diseases and pests through the use of nets and predator–prey strategies rather than the use of chemicals; (3) conservation of resources such as water, soil, biodiversity, and energy; and (4) improvement of biological interactions, biodiversity, and synergies (Fig. 1.2). The idea underlying this new model is based on attempts at answering questions related to ways of feeding the population in the midst of an old model that is not working adequately, as reflected by a rise in the prices of inputs into inorganic farming systems such as unaffordable prices of fertilizers and the negative environmental effects of inorganic fertilizer usage.

1.3 Organic versus Inorganic Farming and Global Food Security

Since the days of Robert Thomas Malthus and his famous Malthusian theory, the ability of the global food supply system to feed the galloping world population has been a major challenge. Two main schools of thought now straddle this debate. One part of this debate argues that conventional methods of production involving high-yielding varieties, synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides inter alia do produce higher crop yields across the globe when compared to agroecology-related methods of production such as organic fertilizers, prey–predator relationships, recycling, and general resource management (Badgley et al., 2007; Abedi et al., 2010). It is a veracity that conventional agriculture has been a major technological achievement in the midst of a doubling human population in the past four decades; more than enough food has been produced to meet global caloric demands, if and only if food was distributed equitably; in reality, some regions have excess while others are faced with the daunting ramifications of food insecurity (Badgley et al., 2007; Abedi et al., 2010). Given the projections of a world population of between 9 and 10 billion people by 2050, Malthusian predictions of future food production remain looming. In fact, with a global increase in meat consumption and a reduction in grain harvest, more appropriate systems of production are mandated if the galloping world population is to be feed. Worse is the fact that the conventional systems do not only continue to lag behind the global crop yield-ban wagon, but they also have repercussions on the environment. These modern methods of production do not only involve high cost but are also associated with soil erosion, pollution of surface and ground water resources, loss of biodiversity, spewing of greenhouse gases (GHGs), inter alia (Altieri, 1995, 2002; Uphoff et al., 2002).

Many have argued that alternate forms of agriculture, such as organic farming, are still not capable of producing as much food as conventional methods of farming. It is argued that organic farming takes up more land, a weakness of organic farming which to many writes off the weaknesses of inorganic farming and related conventional farming methods. Others even ...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Chapter 1. Contribution of Organic Farming Towards Global Food Security: An Overview

- Chapter 2. Fertilizer Management Strategies for Enhancing Nutrient Use Efficiency and Sustainable Wheat Production

- Chapter 3. Pest Control in Organic Farming

- Chapter 4. Fertlizers: Need for New Strategies

- Chapter 5. Integrated Weed Management in Organic Farming

- Chapter 6. Role of Microorganisms (Mycorrhizae) in Organic Farming

- Chapter 7. Interactions Between Flowering Plants and Arthropods in Organic Agroecosystems: A Review and Case Study

- Chapter 8. Fertilizer Management Strategies for Sustainable Rice Production

- Chapter 9. Future Perspective in Organic Farming Fertilization: Management and Product

- Chapter 10. Understanding Organic Agriculture Through a Legal Perspective

- Chapter 11. Bioenergy Production and Organic Agriculture

- Chapter 12. The Potential of Agro-Ecological Properties in Fulfilling the Promise of Organic Farming: A Case Study of Bean Root Rots and Yields in Iran

- Appendix 1. Floral Species (Herb, Forb, or Subshrub) Evaluated for Attracting Parasitoids and Predators in Agro-ecosystems

- Index