The Biology of Thought

A Neuronal Mechanism in the Generation of Thought - A New Molecular Model

Krishnagopal Dharani

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Biology of Thought

A Neuronal Mechanism in the Generation of Thought - A New Molecular Model

Krishnagopal Dharani

About This Book

The question of " what is thought " has intrigued society for ages, yet it is still a puzzle how the human brain can produce a myriad of thoughts and can store seemingly endless memories. All we know is that sensations received from the outside world imprint some sort of molecular signatures in neurons – or perhaps synapses – for future retrieval. What are these molecular signatures, and how are they made? How are thoughts generated and stored in neurons? The Biology of Thought explores these issues and proposes a new molecular model that sheds light on the basis of human thought. Step-by-step it describes a new hypothesis for how thought is produced at the micro-level in the brain – right at the neuron.

Despite its many advances, the neurobiology field lacks a comprehensive explanation of the fundamental aspects of thought generation at the neuron level, and its relation to intelligence and memory. Derived from existing research in the field, this book attempts to lay biological foundations for this phenomenon through a novel mechanism termed the " Molecular-Grid Model " that may explain how biological electrochemical events occurring at the neuron interact to generate thoughts. The proposed molecular model is a testable hypothesis that hopes to change the way we understand critical brain function, and provides a starting point for major advances in this field that will be of interest to neuroscientists the world over.

- Written to provide a comprehensive coverage of the electro-chemical events that occur at the neuron and how they interact to generate thought

- Provides physiology-based chapters (functional anatomy, neuron physiology, memory) and the molecular mechanisms that may shape thought

- Contains a thorough description of the process by which neurons convert external stimuli to primary thoughts

Frequently asked questions

Information

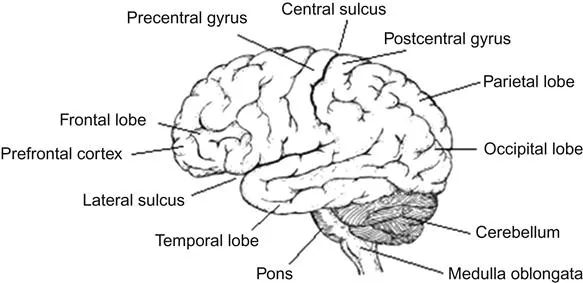

Functional Anatomy of the Brain

Keywords

Overview

General Plan of the Nervous System

Anatomical Considerations

Types of Nervous System

Somatic Nervous System

Autonomic Nervous System

Enteric Nervous System

Types of Neurons

Sensory Neurons, Motor Neurons and Interneurons

Functions of Nervous System