The monster has always been well-dressed and well-loved.

—Austin Channing Brown, I’m Still Here

If you were to look at a picture of me or to see me across the room, you would think to yourself, “There’s a white guy.”

But that would only be because you were socialized to think so. I’m not objectively “white” in skin color; in fact, like most people deemed white, I have skin that is various shades of beige, depending on which body part gets more of the sunshine that activates my limited measure of melanin. In fact, if you had spotted me prior to the 17th century—maybe at a religious procession or a beheading in the town square of one of my European ancestors (you know, just a typical day of entertainment in medieval history)—the racial concept of “white” wouldn’t have crossed your mind at all. You may have attempted to classify me as belonging to one of many European “races” based on my hair color, facial features, and skin tone. Perhaps I might be Anglo-Saxon, descended from Germanic people who migrated to the British Isles; or I might be a Frank, another Germanic tribe that took over Roman Gaul after the Roman Empire. Or my dark hair and brown eyes may have led you to classify me as an Indo-European tribe member from Italy, or possibly an ancient Greek. Those were just a few of the dozens of “races” that were commonly recognized in earlier eras. A few centuries later, most of them were lumped into a new racial category deemed first “Caucasian,” then “white.”

Crystal, a creative, intelligent, hilarious, tall, beautiful, spiritual, justice-seeking woman—who society would categorize as “biracial” under its current racial labeling system—is one of my most thought-provoking friends. One day after I moved to Nashville in 2015, I heard the news of a white supremacist’s killing of nine members of Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina. This news, combined with a string of highly publicized shootings of unarmed African Americans by law enforcement officers, led me, along with many others, to feel deep anguish and frustration.

Several pickup truck owners in my new Southern community, however, were apparently feeling their own frustration. The Confederate flag that lay draped around the killer’s shoulders in his Facebook photos was being scrutinized more intensely. Was it truly an appropriate symbol to fly over the South Carolina state Capitol? After the state’s Republican then-governor Nikki Haley and its legislature agreed that the flag should be taken down, I noticed a copious number of large Confederate flags flying from truck beds around my new neighborhood.

I texted Crystal.

If you are considered white, you may feel disorientation and even defensiveness about Crystal’s challenge. I did. Like most people, I assumed that racial categories were immutable. I had heard of some people attempting to “pass” as another race, and I certainly have been on board for arguing that all races are equal. But to question the very reality of race? To be challenged to shed my whiteness as a solution to what our society was facing? Did that mean everyone should be challenged to “give up” their race, or just white people? It was jarring to consider.

Of course, that was Crystal’s point.

If my circle of friends is any indication, not many 50-year-old white guys ponder the issue of how we came to be classified as white. I can tell by the odd looks and awkward silences I get when I bring it up. It’s just assumed to be a fact of life, like breathing or resenting Tom Brady and the New England Patriots. The origins of race, and whether racial categories are even a valid way to classify people, are not topics that most white people have had to ponder. When race comes up, many of us want to change the subject, because we assume something controversial is about to be said—something that will make us feel guilty.

Most of us also want to see ourselves as champions of equality. Everyone, regardless of race, should be considered equal and treated the same, right? Although this assumption is actually a relatively new development among white people, one that arose during my lifetime, we seem to keep stumbling over ourselves in terms of living this out economically, spiritually, and politically. We assumed that we could cling to our racial identities and just start treating each other better.

But a funny thing has held us back—something we haven’t really wanted to admit. We white people like our whiteness and the way we’ve architected this American culture around it. It works for us. It’s odd but true: in these modern times, most of “us” have been just fine with opening entry into this world of whiteness to “others” with different skin colors—as long as it was on “our” terms.

Crystal’s challenge to me—her white friend who had become so concerned about why this approach hasn’t been working so well—was to go deeper. What is “whiteness” anyway? Why was it invented? (And yes, as we’ll see, it was invented.) Is the existence of whiteness—and perhaps in response, the invention of blackness and other human-created racial categories—the very obstacle to the kind of equality we fooled ourselves into thinking was achieved with the election of President Barack Obama?

The wild pendulum swing of who got elected next is probably a clue.

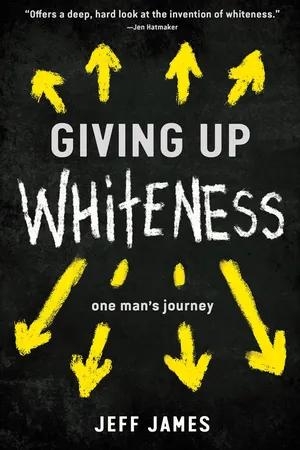

This book is the story of how I took up Crystal’s challenge. After four years of exploring whether her dare was viable and discovering just how deeply a racial lens had shaped my, “I’m one of the good guys” assumptions, I can report one thing for sure: It’s not very simple. Along this journey, I learned more about myself, my country, my faith, and the origins and applications of race than I ever imagined possible. I learned answers to questions I never even thought to ask. I learned why who classifies you and how you are classified carries an immense set of made-up assumptions that lead to a collection of privileges or oppressions, often ebbing and flowing to various extremes, depending on the era you live in and on what piece of soil you reside.

That racial categories carry varying levels of privilege is not a secret to most who are paying attention these days, of course. What was surprising to me, and what I eventually found immensely hopeful, is that we have a say in whether we continue to accept this false and destructive human classification called “race.” To be clear, this challenge was far different from “not seeing color,” a hollow attempt at papering over obvious differences in skin hues, as well as the cultural realities that have risen up around them. No, this was a dare to confront white supremacy by deconstructing its very foundation: whiteness.

So many friends of color have expressed the exhaustion of having to explain, educate, and speak on behalf of their entire race-categorized community to well-meaning white folks like me. That saddens me greatly. Another underlying motivation for this book is to identify my blindness, so others can identify it in themselves. By sharing what I’ve learned, I hope to reduce even a tiny bit of the workload on people of color.

Really, though, I felt compelled to explore Crystal’s challenge and determine for myself: Could I shed this whiteness, this racial construct set before me? I owed my friend an answer.

***

Before Crystal’s text challenge, I had always considered myself part of the solution—not the problem. Experiences from my youth, along with some quality parenting from my mother and father, had planted within me a deep awareness and even sensitivity about injustice and inequality. These seeds from my youth blossomed into an attraction to the words of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X when I was in college. Yet like many white people who grew up in the cocoon of a white-centric community, I wasn’t fully aware of the systemic powers of whiteness. Racism meant you were mean, not that you benefited from a centuries-old structure of domination against people of color.

A few years prior to meeting Crystal, I attended an anti-racism training event called Damascus Road. My congregation, Circle of Hope in Philadelphia, where I lived at the time, offered to send a team for the weekend event. When our church leaders asked for volunteers, I felt compelled to raise my hand. As it turns out, Circle of Hope, despite its funky, hipster Center City Philadelphia vibe, was a church plant of the Brethren in Christ, a denomination with roots in Anabaptist and Mennonite traditions. The church’s relationship to Anabaptist principles began to explain why a commitment to equality, nonviolence, and justice was prevalent, but it didn’t exempt our community from the common misunderstandings, biases, and sometimes egotistical stubbornness that race so artfully inflames. There weren’t a lot of people of color who attended the congregation at the time, but some who did had been expressing frustration with their experiences at the church, despite its stated values. I felt like this Damascus Road experience could be a game-changer for me and the congregation.

Small teams of five to 10 members, mostly from churches and schools around the city, gathered in a library meeting room at Philadelphia Mennonite High School in the Germantown neighborhood. To begin, Conrad Moore, one of our leaders, walked us through a visualization exercise. On a large sheet of paper posted on the wall, he drew a rudimentary sketch of a community with shops, office buildings, stick people, cars, and stoplights. He asked us to imagine that this was an under-resourced community—a “ghetto,” a barrio, or a trailer park. Next, he asked us to describe what we would most often see in the way of buildings, stores, schools, or parks. A few people mumbled some initial ideas, which led others to chime in as we lost our new group inhibitions: “Graffiti.” “Run-down houses.” “Empty storefronts.” “Liquor stores.” “Homeless people.” “Trash.” Then he asked, “Why are people in this community poor?”

“A lack of jobs.” “Inadequate schools.” “Drugs.” “Poor personal decisions.”

We watched as he drew a giant foot at the top of the paper. It hovered menacingly in the white space above the community.

“What institutions have influence or power over these areas?” Conrad asked.

We shared our collective list: banks, developers, government officials, public works boards, boards of education, law enforcement, healthcare conglomerates, media, religious leaders, real estate brokers, transportation officials. The list continued, and it was surprisingly long. I realized how little I had considered the influence of those who make decisions that affect our communities—whether our community is a well-resourced or poorly resourced one.

“Who primarily runs these institutions?” Conrad inquired.

We could see where this was headed. Most, if not all, were run by white people who didn’t live in the community.

A few white attendees began to loosen up. In hopeful tones, they pointed out that things were changing. They shared examples of African Americans who now held leadership roles with local banks, school boards, and even City Hall. After all, Philadelphia had elected its first black mayor, Wilson Goode, in 1984, and the current mayor at that time, John Street, was African American. Even the police commissioner, Richard Neal, was African American.

Aha! Progress against the giant Foot! Still, the group quickly realized that the powers that shaped the circumstances of poor neighborhoods had been in place for generations. While a few of the institutional forces were now managed by people of color, that was a relatively recent development.

Conrad wasn’t quite done with his point. He described the role of gatekeepers: those who have a semblance of power but are bound to fulfill the policies and preferences of their bosses up the chain. “Who does the Latino regional manager of Philadelphia Electric work for?” he asked. A white vice president, most likely, and ultimately a white CEO, was the obvious answer.

“Who does the African American CEO of a regional bank work for?”

“Shareholders,” someone responded. Not surprisingly, the vast majority of investors, especially the ones with a high enough concentration of ownership to influence corporate policy, were white and very wealthy. Only 9% of African Americans and 7% of Hispanics at the time owned any stocks at all. What shareholders—wealthy and divorced from any familial or emotional connection to a poor community—would want their bank to invest equitably in struggling neighborhoods to ensure equal access to resources? Shareholders want a return; wealthy suburban branches making loans to already-resourced folks would certainly deliver a higher return.

The Foot that Conrad had drawn over the community was becoming clearer. Beyond the institutions that were supposed to be “helping,” who owned the liquor stores that were so prevalent in this and other poor neighborhoods? The porn outlets and strip clubs? The waste treatment plants? The overpriced corner convenience stores, which in some cases, were the only place to find food for miles?

Who had passed the laws that were now sending an immense number of African Americans to jail for small-scale drug crimes at rates far higher than white drug offenders? Who were the people investing in and benefiting from that sharp rise in for-profit private prisons, funded by ma...