![]()

1 : Walter De Maria, The Lightning Field

SEEING A FLICKERING LIGHT

Darkling

Devoted to the technologies that make and hold open the illuminated clearing, we have inherited the clear and distinct world of things revealed by the apotheosis of electricity. Indeed, the light that once made a modest clearing in which human beings could build their abode on solid ground now reaches worldwide. Just look at the unearthly photos of our world taken by orbiting satellites and you will see the planetary deployment of modern illumination: the illuminated clearing where man sets up house alongside the things that sustain him has become the sprawl of the global city; darkness and clouds have been banished, along with forests and wildlife. Nothing now escapes the light.

The dream of enlightenment, in apparently fulfilling itself, has arrived at a strange inversion—one that is stated well by Pantope, a character in Michel Serres’s beautiful meditation Angels: A Modern Myth: “They say that cities developed out of clearings in forests; now these ‘clearings’ appear like ‘darklings’ in between the cancerous growths of light from the city.”1 The clearings are now dark spots, and, even worse, these darklings have been lost and forgotten amid the global omnipresence of the light administered by human industry. Heir to the sun of the enlightenment and the electric factory, our daily life seem to know no night, no dark in the sprawling omnipresence of illumination—and so we know no place to see the light and the clearing it makes. This lends support to the suspicion felt by some of us that the enlightened world and the objects it presents to our grasp is increasingly deserted, as all dissolves in the glare of too much light.

We must, I suspect, go to the darkling to find the clearing.

Not content with leaving the “darklings” to be lost in all the light, those disenchanted with modern disenchantment dream of sparing them from oblivion and thereby saving the things that come to light there. Like the mystics and ascetics of another age, these disenchanted moderns go into the desert to see another light. What they seek is the darkness in which they might see the light. “The light,” after all, “shines in the darkness.” It does not shine where there is full or total light, and the shining does not extinguish the darkness without obscuring the light itself.

FIGURE 4. Walter De Maria, The Lightning Field (1977). Permanent earth sculpture: 400 stainless steel poles arranged in a grid array measuring one mile by one kilometer; average pole height 20 feet 7 inches, pole tips form an even plane. Quemado, New Mexico. Photograph by John Cliett. © Dia Art Foundation, New York.

A third image (fig. 4), therefore, to add to the first two: The Lightning Field by Walter De Maria, a work that the art critic Kenneth Baker has praised as “the ultimate work of Land Art.”2

THE LIGHTNING FIELD

The lightning field itself covers a parcel of ground one mile wide by one kilometer long. Four hundred polished and sharpened steel poles, spaced at intervals of 220 feet, emerge from the earth in a desert plain in New Mexico, making a grid twenty-five poles wide by sixteen poles long. The length of the poles varies with the surface of the earth so that all rise to the same height above sea level, making for a “smooth visual recession that allows you to see the poles imposing a framework of pictorial perspective on the terrain viewed through them. . . . The Lightning Field coordinatizes a part of the plain. . . . A network of locations, The Lightning Field gives the impression that the natural reality of the plain has become observable in a new way, even in a sense for the first time.”3 Perspective is the way to organize the space of a picture, something an artist does to open or clear a space for the figures and shapes he will then create. It is a preliminary to creating the picture and the placement of things within it. Finding a perspectival grid and a network of orienting coordinates here in the barren vastness of the remote desert is surprising, because one does not often look to the desert as an organized place. The presence of such a grid here, on a plain that extends some thirty miles beyond to the Datil Mountains, make this place one where we encounter the barest minimum, the inchoate emergence of the organization of space into a human world. One comes here to attend the very opening of a world, the moment of its flashing into being amid the empty, indifferent void of the “natural” plain and homogeneous desert.

The poles all rise to the same height so that one can imagine, De Maria says, a plane of glass (I think, too, of the sky) touching each of the points, its weight evenly distributed and borne aloft. The artificial flatness of this plane works to lift up or bring forward the contour of the contrasting natural earth below. Or do the poles penetrate the earth, sinking under the weight of a descending sky? Here, it is difficult to decide if you are witnessing the creation or the destruction of a world: do the poles rise and measure an opening that separates earth and sky, or are they pressed down as the distance between earth and sky collapses apocalyptically, leaving only these “emblematic relics of the world,” the faintest traces left of its having been, “daring you to think of them as all there is left of the world”?4 Is this the dawn of a habitable clearing or its twilight? The Pueblo peoples of the surrounding land, which include most notably the Zuni and the Hopi, are also sensitive to this ambiguity. They identify many places in this region as sites where their ancestors crawled from the caves and depths of the earth in which they had been made and emerged onto the earth’s surface, where they breathed air under the sky—and equally many places as sites where one can make the reverse passage, out of this world and into the other.

As De Maria’s title suggests, the steel poles are powerful attractors of lightning strikes in an area that was carefully chosen not only for its isolation and expansive view, but also for the power and energy frequently manifested there in severe climatic effects. Extremes of atmospheric moisture, wind, and temperature are accompanied by heightened electrical activity. Strong winds of thirty to fifty miles an hour are said to blow steadily for days sometimes in the spring; only eleven inches of rain fall each year; thunderstorms can be seen from the field on an average of one in six days throughout the year; and on one out of every ten days a lightning storm passes directly over the field. Though not common, lightning strikes are unusually frequent in the area, charging the experience of being there with the promise of great power, but also with the unmistakable threat of destruction by the very energies that the poles seem to invite.

. . .

Look again, now at the three images together (figs. 5, 6, and 7).

Like Wolff’s Lucem post nubila reddit and “The Apotheosis of Electricity,” the picture of The Lightning Field is organized in two tiers: an earthly landscape below and clouds above. But unlike the clouds that, in the earlier images, show themselves in order to be banished, the clouds above The Lightning Field show no sign of dispersing; they make no opening or clearing for the otherworldly, supernatural, or transcendent to reveal itself. Indeed, they are likely gathering, forming a lid that closes over the whole scene. All of this gives the picture a great horizontal emphasis but little sense of vertical movement and a corresponding absence of feeling of possible ascent or escape.

There is one possible exception, an exception that flashes within this still closed picture.

The Lightning Field differs from the previous two images in that here the light shines when the clouds do not part. The smiling sun and the celestial electric factory have yielded to the wild flash of lightning—which in its jagged flickering creates momentary and momentous visions, the striking presence of these poles. In fact, this light flashes only when clouds and darkness remain in the picture. The schematic geometry of point, line, and cone cannot account for how this work of illumination brings a world to light. There is no cone of rays emanating in straight lines from a depicted point source, gathering all together and holding it in an illuminated clearing. There is no single point or source from which the rays emerge, seeming as they do to come from beyond the frame of the picture, lost in the unrepresentable darkness of the clouds. This is a fluctuating light, a swerving, forking, bifurcating zigzag that brings things into the picture only momentarily and resists being pinned down in one particular place. “Capricious,” in the words of Camille Flammarion, “it is impossible to assign it any rule. . . . As many strikes as extravagances. . . . [It] does not give any explanation; it acts, that’s all.”5 We can speak of its effects with more certainty than of it itself.

FIGURE 5. Frontispiece from Christian Wolff, Vernünfftige Gedancken von Gott, der Welt und der Seele des Menschen auch allen Dingen überhaupt den Liebharen der Wahrheit (1720). Rare Book Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

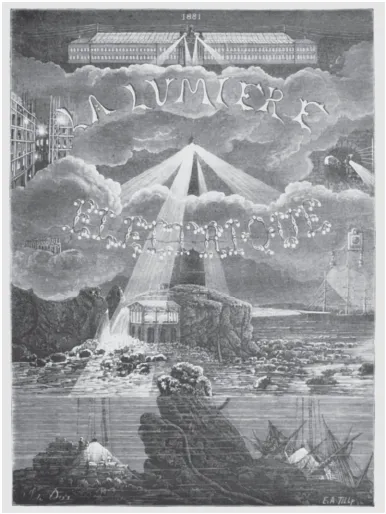

FIGURE 6. Title page from La lumière électrique (1882).

FIGURE 7. Walter De Maria, The Lightning Field (1977). Photograph by John Cliett. © Dia Art Foundation, New York.

This recalls the description Michel Serres once offered of the chaotic cloud of falling atoms out of which the cosmos was born, according to the ancient philosopher Lucretius. “The lightning, in its oblique flight, crosses the rays of the rain. Now here, now there; ripped from the clouds, the thunderbolts flash from everywhere. . . . Obliqueness of a lightning strike against a parallel field.”6 Very nearly a description of the scene in which scientists once believed life emerged, when a lightning strike sparked catalytic processes in a primordial soup. As in Lucretius, the zigzagging motion we see in The Lightning Field crosses with its randomness the law-governed, linear trajectories of objects falling through clear and empty space, and in this unexpected flash, the connections and conglomerations of the things that make up a world fall into place: momentously and momentarily, the poles form constellations.

Writing in a special issue of the journal Antigone, a literary review of photography, the noted art historian and philosopher Georges Didi-Huberman commented on the difficulties faced by those who have wanted to make a picture of the world that includes lightning. “How can one fit the trace obtained in the photograph into a perspectival scheme? . . . The evidence for the relation form / ground that the image of the lightning gives is part of a long tradition of hypotheses and recurrent questioning about the exact place of what one does nevertheless see so distinctly outlined against the ground of a stormy night.” Is the lightning shaped like a helix whose projection only seems in our photograph to be a line (as nineteenth-century German meteorologist Ludwig Kaemtz hypothesized)? Or are the lines we see only the irregular edges of a thick dark cloud behind which the lightning truly flashes (as his English contemporary Michael Faraday supposed)?7 Out of what depths does the lightning strike? Where is this thing we see so distinctly in the picture? What edge defines its place? Recalcitrant to being depicted clearly and distinctly in a picture of the world, lightning is not represented so much as presented. The “nonrepresentable” presents itself, as the lightning flash is the light in which it itself is portrayed; there is no need for the flash produced by our high-tech cameras to open a clearing prior to its appearance, and in fact, such a flash often causes the lightning to vanish. “The lightning is itself light’s writing ‘which imprints itself by itself on the sensitive film,’ detaching itself from a dark night.” “The instrument of this revelation . . . was photography.”8 The photographic film, its dark negative, is the sole place where this presentation is revealed in a picture.

What comes to light in such a picture of the world? What comes to light when the lightning flashes in the desert darkling? There is no permanent place to rest or home to lay your head, nothing that abides permanently alongside you granting you the felt stability of an anchor on solid ground. It is as if the sea and flowing river of Lucem post nubila reddit and “The Apotheosis of Electricity” have returned as the shifting sands of the desert. On this impermeable surface, there is little ground for building or laying a foundation. Few things have come to stand constantly and permanently here in the clearing momentarily illuminated by the lightning flash. You see not solid and stable objects, but ephemera, poles that happen in a flash and vanish. The lightning brings things to light not so much by leading them to solid ground but by making them flash and flow and flow away, like waves rising and crashing.

Hardly the dawn of a new day, yet it is where one goes to see the world flash into light.

. . .

Each summer from May to September, hundreds of supposedly disenchanted moderns go to the desert in groups of no more than six at a time harboring sometimes faint, sometimes strong hopes that lightning will strike on the day they have chosen to be there. They pay no small fee and devote a large amount of supposedly scarce time and energy in the expectation of no greater compensation than a glimpse of flashing light.

The light they seek is the light that comes when the clouds do not part.

The vision they seek is solicited by the lightning poles.

The visions they receive are things that happen and, happening, flow away.

Into the land of enchantment: In search of lost causes

In the summer of 2004, I joined the disenchanted moderns (moderns disenchanted with modern disenchantment?) and made a journey to the provinces of New Mexico looking for The Lightning Field. Reminded by the license plates that New Mexico is “the land of enchantment,” I wandered off into the darkling of the desert to see the light. What had awakened this desire to seek the darkling and spare its clearing from oblivion is hard to say. It was a time of fullness for me. Things were finally falling into place. All things, or at least many of the things, I had most wanted (but thought had drifted away) were now rendering themselves to me. I had just completed the first year of a new job, the long sought and anxiously awaited tenure-track position as a college professor. My first child had been born a little over a year before. And sometime in the three months between the birth of my daughter and the beginning of my job, I had bought my first house. After some dark years, everything was looking bright. My ship had come in.

I was not the first comfortable but disenchanted modern to stray into these deserts. One of the more interesting of those who preceded me was Aby Warburg (1866–1929), widely recognized as one of the founding fathers of the modern discipline of art history. Those profoundly influenced by Warburg include Erwin Panofsky and Ernst Gombrich, both of whom would go on to give th...