- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

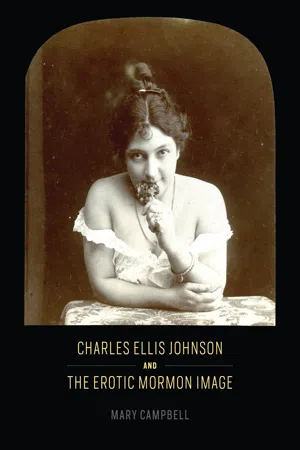

Charles Ellis Johnson and the Erotic Mormon Image

About this book

On September 25, 1890, the Mormon prophet Wilford Woodruff publicly instructed his followers to abandon polygamy. In doing so, he initiated a process that would fundamentally alter the Latter-day Saints and their faith. Trading the most integral elements of their belief system for national acceptance, the Mormons recreated themselves as model Americans.

Mary Campbell tells the story of this remarkable religious transformation in Charles Ellis Johnson and the Erotic Mormon Image. One of the church's favorite photographers, Johnson (1857–1926) spent the 1890s and early 1900s taking pictures of Mormonism's most revered figures and sacred sites. At the same time, he did a brisk business in mail-order erotica, creating and selling stereoviews that he referred to as his "spicy pictures of girls." Situating these images within the religious, artistic, and legal culture of turn-of-the-century America, Campbell reveals the unexpected ways in which they worked to bring the Saints into the nation's mainstream after the scandal of polygamy.

Engaging, interdisciplinary, and deeply researched, Charles Ellis Johnson and the Erotic Mormon Image demonstrates the profound role pictures played in the creation of both the modern Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the modern American nation.

Mary Campbell tells the story of this remarkable religious transformation in Charles Ellis Johnson and the Erotic Mormon Image. One of the church's favorite photographers, Johnson (1857–1926) spent the 1890s and early 1900s taking pictures of Mormonism's most revered figures and sacred sites. At the same time, he did a brisk business in mail-order erotica, creating and selling stereoviews that he referred to as his "spicy pictures of girls." Situating these images within the religious, artistic, and legal culture of turn-of-the-century America, Campbell reveals the unexpected ways in which they worked to bring the Saints into the nation's mainstream after the scandal of polygamy.

Engaging, interdisciplinary, and deeply researched, Charles Ellis Johnson and the Erotic Mormon Image demonstrates the profound role pictures played in the creation of both the modern Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the modern American nation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Charles Ellis Johnson and the Erotic Mormon Image by Mary Campbell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Royal Saint

An enormous religious imagination has been compromised (though not betrayed) by its descendants, even if one gets very little sense of any Mormon consciousness of that departure from [Joseph] Smith during a visit to Salt Lake City.

—HAROLD BLOOM, The American Religion, 1992

On May 29, 1903, Teddy Roosevelt visited Salt Lake City, Utah. With the 1904 election looming, the incumbent president had set out on an eight-week tour of western America earlier that spring, giving 263 speeches in twenty-five states before returning to the White House in June. His day trip to Salt Lake came toward the end of his fourteen-thousand-mile journey, sandwiched between his visits to Shoshone, Idaho, and Laramie, Wyoming. Stepping up to the podium at the city’s Tabernacle and gazing out at the seven thousand eager listeners who had assembled to greet him, Roosevelt extolled his audience’s pioneer heritage. “You took territory which at the outset was called after the desert,” he proclaimed, “and you literally—not figuratively—you literally made the wilderness blossom as a rose.”1

Roosevelt was preaching to the choir with this pronouncement—literally and figuratively. Since 1873, the Tabernacle had been home to the state’s nationally celebrated Mormon Tabernacle Choir, winner of the silver medal at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and fresh off its own 1903 tour of Northern California. Many of these renowned choristers sat in the president’s audience that day, listening as he sang their ancestors’ praises. At the same time, Roosevelt’s speech overtly echoed the way that the Latter-day Saints (LDS), or Mormons—still the majority in turn-of-the-century Utah—liked to talk about themselves. “We had not much to bring with us,” the LDS apostle Orson Pratt reminisced of the Saints’ arrival in the Salt Lake Valley in the summer of 1847, “but we came trusting in our God, and we found that the Lord really fulfilled the prophecy of Isaiah, and made the wilderness to blossom as the rose, made the desert to bloom as the Garden of Eden.”2 With his own language of wilderness and roses, Roosevelt tapped into such cherished Mormon stories, evoking the original LDS settlers’ unswerving determination to transform the Uintah Basin’s arid landscapes into the verdant abundance of God’s own garden.3 In the process, he used the Saints’ frontier past to cast the current generation of Mormons as a model of American tenacity, responsibility, and success. “I ask that all our people from ocean to ocean approach the problem of taking care of the physical resources of the country in the spirit which has made Utah what it is,” he declared.4 Only seven years into statehood, the country’s newest addition to the Union basked in the glow of the president’s admiration.5

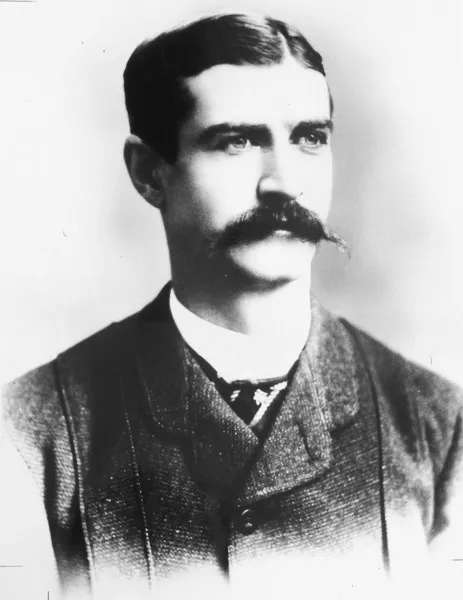

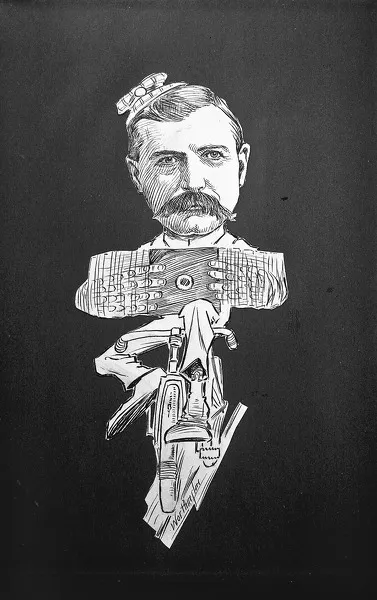

Befitting the magnitude of the occasion, Roosevelt’s host, Utah senator Thomas Kearns, hired a photographer to memorialize the event. Outfitted with several cameras and undoubtedly groomed to dapper perfection, Charles Ellis Johnson (1857–1926) (fig. 1.1) arrived at the senator’s palatial home immediately after the president’s speech. Setting up his equipment on the lawn, Johnson photographed Roosevelt and his private secretary, William Loeb, posed with Kearns and Salt Lake City mayor Ezra Thompson (fig. 1.2). As if visually reiterating the president’s own tribute to Utah’s exemplary citizens, Johnson framed the shot to include the numerous American flags that decorated the front of the Kearnses’ mansion. Moving inside, he captured a stereoscopic view of the elaborate table Mrs. Kearns had set for the formal breakfast she and her husband were holding in the president’s honor, once again including the Stars and Stripes on prominent display. Although they don’t appear in Johnson’s picture, the senator’s wife had placed a miniature American flag in front of each place setting before Roosevelt entered the room. At the end of the meal, the sixth LDS prophet, Joseph F. Smith, took his home as a memento of the festivities.

Figure 1.1. Anonymous, portrait of Charles Ellis Johnson. Photograph, ca. 1890. Courtesy of the Deseret News.

Figure 1.2. C. E. Johnson, untitled photograph of Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas Kearns, Ezra Thompson, and William Loeb. Photograph, 1903. Ronald Fox Collection, Salt Lake City.

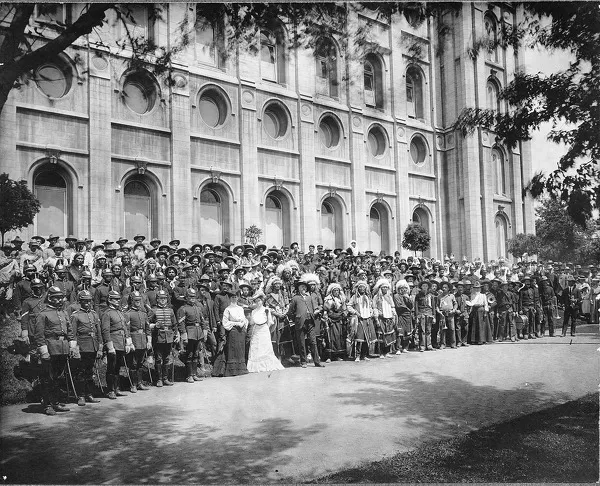

In all likelihood, Johnson would have found a way to meet and photograph Roosevelt even without the Kearnses’ invitation. During the 1890s and early 1900s, he and his camera seemed to appear every time something interesting happened in or around Salt Lake City. When Buffalo Bill Cody came to town in 1902, Johnson persuaded the celebrated showman and his troupe to pose for a picture in front of the Salt Lake Temple (fig. 1.3). When a battalion of Buffalo Soldiers passed through the city on their way to the Spanish-American War in 1898, Johnson hauled his equipment onto a rooftop in order to get a photograph of the entire regiment marching down Main Street. When, in 1903, a fragile-looking young woman named Aurora Hodges confessed to murdering a traveling salesman just outside Salt Lake City, Johnson managed to shoot her stereoscopic portrait in the jail yard, discreetly cropping her handcuffs out of the frame.

Figure 1.3. C. E. Johnson, untitled photograph of Buffalo Bill Cody and his troupe in front of the Salt Lake Temple, Salt Lake City. Photograph, 1902. Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave, Golden, Colorado.

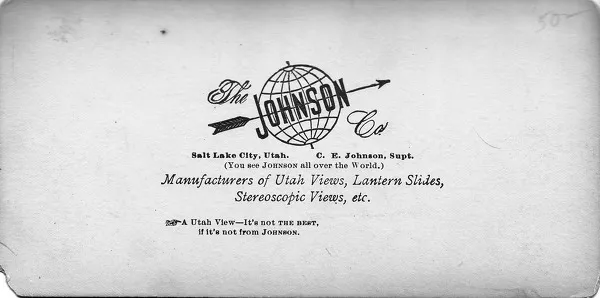

Johnson took thousands of pictures like these over the course of his long career as a photographer and stereographer, pictures that he sold in a variety of formats and a multitude of ways. Cabinet cards, stereoviews, news photos that he offered to the Salt Lake papers for a dollar apiece, postcards that he marketed to tourists at his downtown photography supply and souvenir store—Johnson never limited himself when it came to his choice of format or the chance to make another sale.6 He did, however, focus his lens (or in the case of his stereo camera, lenses) primarily on Utah. A cosmopolitan to the bone, Johnson loved to travel. As his trademark proudly declared, “You see Johnson all over the World” (fig. 1.4). Overstatements aside, he seized every opportunity he could to see what lay outside Salt Lake City, eventually visiting San Francisco, Chicago, New York, Rome, Paris, and London. In 1904, Johnson even spent more than six months in Jerusalem, taking roughly two thousand photographs of the Holy Land.7 At base, however, Johnson was a Rocky Mountain man. He walked into Utah when he was three years old, holding on to his mother’s hand, and he stayed there until the last decade of his life.8 To borrow from that great poet of the American West, Wallace Stegner, Salt Lake City was Johnson’s Paris and his Rome.9 He spent the better part of his fifty-nine years documenting it in pictures.

Figure 1.4. C. E. Johnson, the Johnson Company trademark. Stereoview mount, ca. 1900. Author’s collection.

In particular, Johnson lavished his photographic attention on all things modern. The first underground telephone wires in Utah, the state’s first automobile, the first phonographic recording of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir—if it was new or involved cutting-edge technology, Johnson found it and photographed it. Or bought it, or wore it, or rode it, or invented it. While many of his generation clung to the pen, Johnson used a typewriter with a bright purple ribbon. In an LDS culture that prized live choral music above all other entertainments, Johnson owned a full-symphony version of a player piano, a Rube Goldberg–esque machine called an orchestrion. Even his decision to become a photographer reveals Johnson’s love of innovation, and mechanical innovation most of all. The medium was in its early years when he was born, and still too novel and too machine-based to be fully accepted as its own art form during his professional prime. Johnson reveled in this newness, inventing and building his own state-of-the-art cameras.10 Kodak’s “[George] Eastman didn’t have anything like Charlie had,” his sister-in-law Maude later remembered.11 Loading one of these contraptions into his bag and jumping onto his American Star bicycle (itself an 1890s craze), Johnson cut a figure every bit as current as the sights he set out to capture.

Salt Lake took notice. On February 24, 1900, the city’s Daily Tribune newspaper published a caricature of Johnson rocketing along on his bicycle (fig. 1.5).12 In this sketch, Johnson pedals with one leg and steers with the other, his hands working his camera so feverishly that they fracture into a mechanical blur. True, Johnson appears calm, even reflective, from the neck up. According to family legend, his mother, Eliza, was the illegitimate child of an English nobleman, born in London but shipped off to the United States with her mother and stepfather when she was a young girl. “Her aristocratic face always suggest[ed] a noble lineage,” Johnson’s sister Rosemary remembered.13 Apocryphal or not, the story suited the public persona that Johnson cultivated. Throughout his life, he projected an air of well-bred refinement. With his impeccable clothing and traces of his mother’s British accent (not to mention his enviable height and bone structure), he struck others as genteel, lightly patrician even. As the Tribune drawing suggests, however, he was always too fascinated by the outside world to move through it slowly or to limit himself to a single endeavor. “If Charlie Johnson could have just focused on one thing at a time,” his great-grandnephew recalls, “he would have been a millionaire.”14

Figure 1.5. Worthington, caricature of Charles Ellis Johnson from the Salt Lake Daily Tribune. Drawing, February 24, 1900. Courtesy of B. Ashworth’s Rare Books and Collectibles, Provo, Utah.

Such concentrated attention just wasn’t Johnson’s modus operandi, however. Even though he probably never actually tried to load a glass plate into the back of his camera while steering his bike with his knees, he constantly pursued more than one career at a time. In addition to working as a professional photographer from the early 1890s until his death in 1926, Johnson manufactured and sold a successful line of patent medicines under the label Valley Tan Remedies (VTR), operated his own printing press, acted as the Utah correspondent for the New York Dramatic Mirror theatrical newspaper, distributed American Star bicycles, and served as the vice president of Salt Lake’s Social Wheel bicycle club. According to the blurb that appeared beneath his Daily Tribune caricature, he also worked as a traveling salesman as a young man, distributing “baking powder, cloves, preserved ham, kerosene, whale bone, oatmeal and hair dye.”15 At one point, Johnson’s stationery (he designed and printed it himself) featured three different logos: one for VTR; one for a separate pharmacy business he started with his friend Parley P. Pratt; and one for the photography studio he initially ran with a man named Hyrum Sainsbury.16 More than thirty years before his fellow Utahn Philo T. Farnsworth developed the technology that would eventually lead to the invention of television, Johnson exhibited a decidedly televisionistic mode of attention. Like the twentieth-century channel surfer or the twenty-first-century Internet hound, he jumped from one thing to another and back again with tremendous speed. Views, vocations, interests—it didn’t matter. Like the Daily Tribune’s dashing camera-creature on wheels, Johnson raced from one sight to another, freezing each on glass before speeding off to the next attraction.

There’s a catch here. Or at least a tension. Because at the same time that Johnson adored the new, he was part of a culture that worshiped the old. For most of his life, he belonged to a religion that worked diligently to recreate the biblical past in the here and now. Like the rest of his family, Johnson was a Mormon. And not just any Mormon. Although his mother’s nobility might have been in question, that of his father, Joseph Ellis Johnson, was not. On his father’s side, Johnson descended from pure LDS aristocracy. Joseph Ellis had converted to Mormonism with his mother and fifteen siblings in 1831.17 This was only a year after the faith’s original prophet and founder, Joseph Smith, published the Book of Mormon in Palmyra, New York. The Johnsons were among the first families to convert to Smith’s new religion in toto.18 The prophet loved them for their early dedication, and he often referred to them as the “Royal Family.”19 In keeping with this favored status, Smith asked Joseph Ellis to “bear him company” as he rode to the Carthage, Illinois, jail where a raging mob would murder him in 1844.20

After Smith’s death, the Royal Johns...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- 1 A Royal Saint

- 2 Civil Saints

- 3 Johnson’s New Century Girls

- 4 Mormon Harems

- 5 Lady Saints

- 6 Stereoscopic Saints

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index