eBook - ePub

Navigating among icebergs

Lessons from the Titanic applied to leadership

Juan M. Serrano

This is a test

Share book

- 138 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Navigating among icebergs

Lessons from the Titanic applied to leadership

Juan M. Serrano

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

After analyzing this case study with thousands of executives from all over the world, the author proposes the legendary story of the Titanic as a means to draw out practical lessons and highlight important mistakes that should be avoided. Especially valuable for teams that are good at what they do, but that want to ensure the sustainability of their success.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Navigating among icebergs an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Navigating among icebergs by Juan M. Serrano in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Contabilidad. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Negocios y empresaSubtopic

Contabilidad1. That night back in April 1912…

Now, I want you to imagine yourself in the following situation. It’s 11:40 pm on Sunday, April 14, 1912. In the crow’s nest of the Titanic stand Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee, the two lookouts on watch at that time who are waiting to be relieved of their duty in just 20 minutes’ time.

They joke, seemingly relaxed, and they’ve obviously been very calm throughout their shift. In the James Cameron film, they wanted to capture this confident attitude (which seems to have prevailed among most of the ship’s crew) in a variety of ways. Among these is this scene where Fleet claims to his partner’s amusement that he has the ability to “smell ice” at great distances. He assures him that if they were ever to find one of those giant chunks of ice (typical at that time of year and in those latitudes of the North Atlantic), he would be able to sense its presence long ahead of time. That was his special ability. Later we’ll return to this scene and reflect on this moment.

In a matter of seconds, the faces of both men change. They cannot believe what they see before them: The very tip of an enormous iceberg directly in front of them and just off to the starboard side.

Immediately, Fleet rings the warning bell, contacts the helm using the internal telephone, and raises the alarm. On the bridge, the first officer, William Murdoch, quickly gives a series of orders in a perfectly synchronized chain.

The first is to the rudder man: “All astarboard.”

Almost simultaneously comes the second command, this time to the engine room: “Full astern.”

The boilers are shut down. The propellers stop and immediately begin their full reversal. The 15 security hatches are closed, creating 16 watertight compartments that divide the ship’s hull from stem to stern.

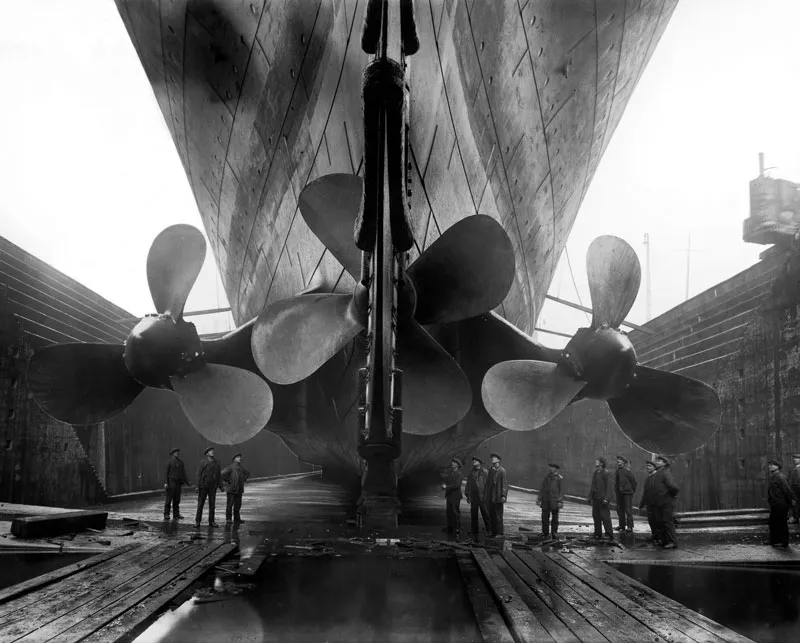

Each piece of machinery has gigantic proportions, from the boilers (4.5 meters in diameter) to the three propellers (the central one is seven meters in diameter), to the engines… Everything is monstrously large.

At this point, “the question” arises.

The curious thing is there are three very different groups aboard the ship asking themselves the same question at the same time.

These are three groups with different levels of perspective, on the one hand, and three groups with different levels of responsibility, on the other.

No one seems to understand what’s happening.

The question is: “Why don’t we see any results from the actions we’re taking to handle this situation?”

These are seasoned seamen, technically brilliant, with decades of experience. They’ve made maneuvers of this kind, and even more drastic ones, hundreds of times over the course of their professional careers.

This maneuver in particular, port round the iceberg (which we will later analyze), was one they’d performed on many occasions, and it had always proven successful. But today – they thought – we’re not getting any results, and the worst is that no one can understand why!

Meanwhile, Murdoch looks anxiously at the bow with the angst of someone who can’t do anything else, combined with the insufferable impatience of seeing that the bow is turning far too slowly to port. These agonizing moments are clearly reflected in Murdoch’s face. He’s sweating, clenching the railing, overwhelmed. These few seconds seem like an eternity.

Finally, the point of the bow slips just to port of the block of ice, and immediately the entire ship feels a terrifyingly deep shudder as the starboard side scrapes along the submerged mass of the iceberg in violent friction.

There’s a sudden shaking, which Murdoch, still clutching the railing, experiences as if it were an earthquake. The bridge rattles. The ship’s wheel shakes violently in the hands of the rudder man. A gash opens in the hull’s starboard bow holds and water explodes through them, wiping out everything in its way.

The perception of what’s happening could not be any more different among the passengers and even some members of the crew. On the starboard foredeck, some passengers play with the ice that has fallen off the iceberg, as if the whole thing is a strange joke.

In the forward holds, the crew and passengers who suffer the effects of the water entering the hull see things in an entirely different light.

Murdoch issues the counter order: “Hard to port,” and activates the mechanism that closes the ship’s watertight compartments. It’s a distressing moment, and not only because of what’s happening. What’s truly awful is the feeling of impotence, lack of control, and the inability to achieve the desired results.

William Murdoch is a hardened seaman, a true professional used to managing adversity on the high seas. It’s precisely for this reason that he’s been chosen by Captain Smith to be the Titanic’s first officer. Murdoch is no stranger to suffering, but the sensation of lacking control is a new one. In addition to this, there is the increased stress of not knowing why the maneuver he has used so many times in his life isn’t working on this day.

The gash in the hull continues down the starboard side toward the stern. It has already scraped all the way to the ship’s fourth watertight compartment and the pressure of the inflowing water is overwhelming.

The tension isn’t just tangible on the bridge. Now it shoots vertically, from the holds and boiler rooms to the crow’s nest where the men on watch are immersed in a heated discussion. Reginald Lee scolds Fleet: “Didn’t you say you could smell an iceberg a mile away? You damned idiot!”

It all happened so fast: The iceberg is now behind the ship after its violent scrape along the length of the forward third of the starboard hull. For many it seems the danger has passed. Some think it was nothing but a big scare in the end. What they don’t know is that the ship has been mortally wounded and that their happiness at not having struck the iceberg head-on will be precisely the fateful circumstance that signs their death sentence.

On the captain’s bridge, Murdoch isn’t at all at ease. He orders the time of the collision to be entered into the ship’s log: 11:40 pm. Just then, the captain enters the bridge and asks, “What just happened?”

Murdoch informs him of the iceberg and explains the maneuver he ordered. Judging by the captain’s reaction, it’s clear he would have done the same. He doesn’t correct Murdoch in any way, and the only orders he adds now (to close the watertight compartments) are precisely the ones Murdoch has already given. In reality, the maneuver chosen by Murdoch is the same that any good seaman of his day would have ordered upon seeing an obstacle at such a short distance from the ship.

Captain Smith orders the ship to be halted to assess the damage and make sure everything is all right.

Down below, as we said before, the passengers are experiencing the event in the most unimaginable variety of ways. While those in third class (closer to the bottom of the hull) are now stepping into water as they get up from their bunks, those in first class are feeling no repercussions of the collision whatsoever. They simply wonder a bit at the vibration they felt at the moment of impact and, at most, they’re curious.

Andrews (the chief engineer presiding over an enormous team of professionals who designed and supervised the construction of the ship) is very worried and heads off quickly with the ship’s plans in hand to get information about what’s happened. Andrews senses something has gone terribly wrong. You can see it in his face. There’s so much at stake. The tension among those that know what has happened is enormous.

No one is fully aware of the damage inflicted just yet. The ship appears to be stable. Unlike many other shipwrecks (such as the wreck of the Lusitania), the Titanic shows no signs of instability. Absolutely nothing appears to indicate that the ship’s safety might be in jeopardy. The iceberg, in fact, is now safely and calmly floating away to stern, the ocean is completely calm, and some passengers even continue to play with the chunks of ice that remain on the foredeck.

It’s now just before midnight, and still no one is fully aware of the situation at hand. But therein lies the tragedy: The ship will go down. It’s only a question of time. The Titanic will never again see the light of day. When the sun rises, she will be at the bottom of the ocean, nearly 4,000 meters below the surface.

2. The dimensions were impressive… Organizations “too big to fail?” [Taller towers…]

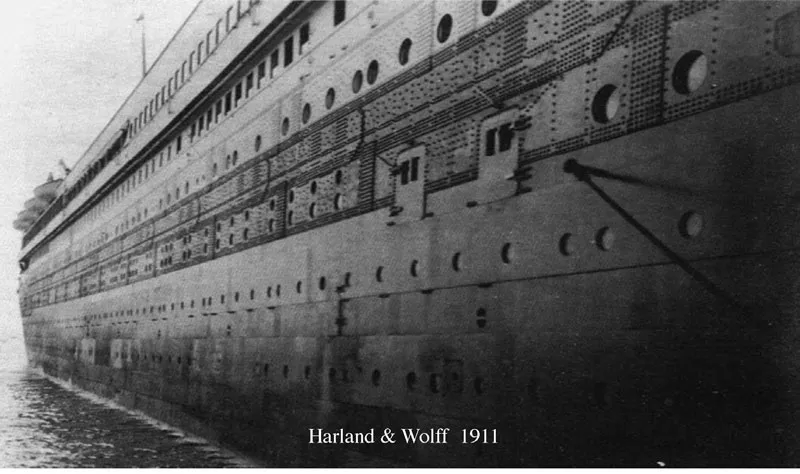

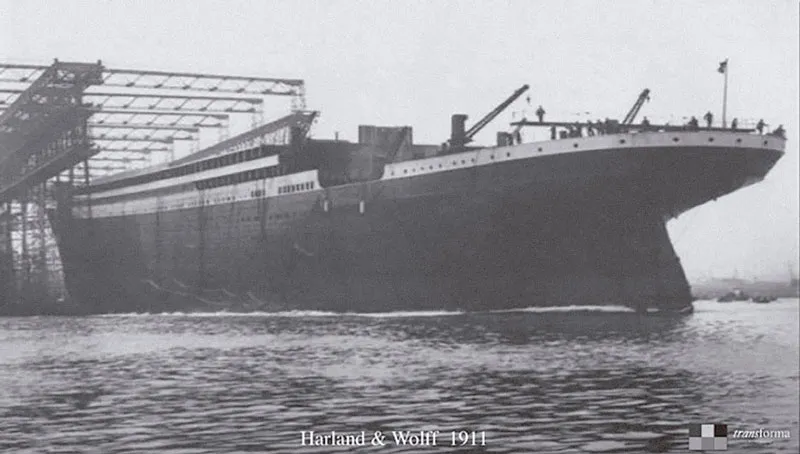

On May 31, 1911, the launching of the Titanic took place amidst enormous expectations. It was the event of the year. Over a hundred thousand people congregated to witness the most advanced and largest piece of technology ever created in the history of mankind.

Later on, we’ll discuss the Titanic’s dimensions and technology, but I emphasize that the whole thing was nearly unimaginable at that point in time. It was easily the greatest concentration of technology of that day and age. We’re talking about very different technologies that ranged from naval design to telecommunications, from propulsion breakthroughs to the latest features in passenger comfort.

It’s difficult to imagine what the Titanic represented in 1911 or to gauge the impact she had on people who had recently entered a new century. The advances were coming at a breathtaking pace, and the Titanic embodied all the signs of a new era for mankind. She was majestic, powerful, robust, and immense. The Titanic was much more than just a big ship: She was the largest moving object ever built by man.

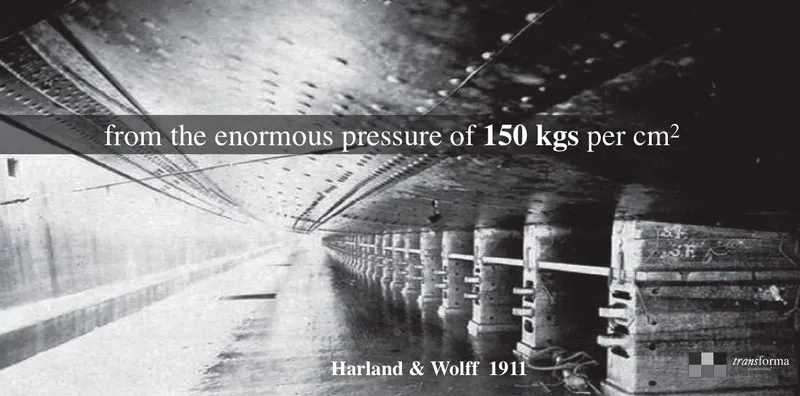

For the ship’s launch, they used 22,000 kilograms of soap, oil, and grease to get her sliding down the rails into the water while protecting the supporting structure that held her hull under the enormous pressure of 150 kilograms per square centimeter.

Expectations were extremely high. Among other things, the fact that it took 15,000 people to build the ship left the world completely enthralled.

Those who ever had the chance to see the ship’s interior were literally shocked by the sight of the four giant engines, each one the size of a three-story house. The ship was impressive.

The day they transported the Titanic’s anchors from the foundry to the shipyard, all of Belfast gathered in the streets to witness what none of them believed to be possibl...