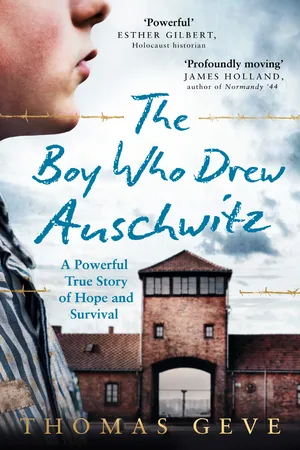

CHAPTER 1

STETTIN AND BEUTHEN 1929–39

I was born in the autumn of 1929, in Stettin on the Baltic, near the Oder in Germany.1 Mother, too, had been born there, while Father hailed from Beuthen in Upper Silesia. My father had studied medicine and had served briefly in the First World War before taking over the practice of Dr Julius Goetze in Stettin. Now established as a General Practitioner with his own practice, he fell in love and married my mother, Berta, the doctor’s daughter.

As a toddler, strange faces seemed to have frightened me. Like most babies, my pastime was crying. The nightly wail of the siren that called out the voluntary fire brigade terrified me. For it sounded like the howling of a monster lurking in the dark, eager to snatch me away at the first opportunity.

Picking the best tomatoes – Stettin, 1933.

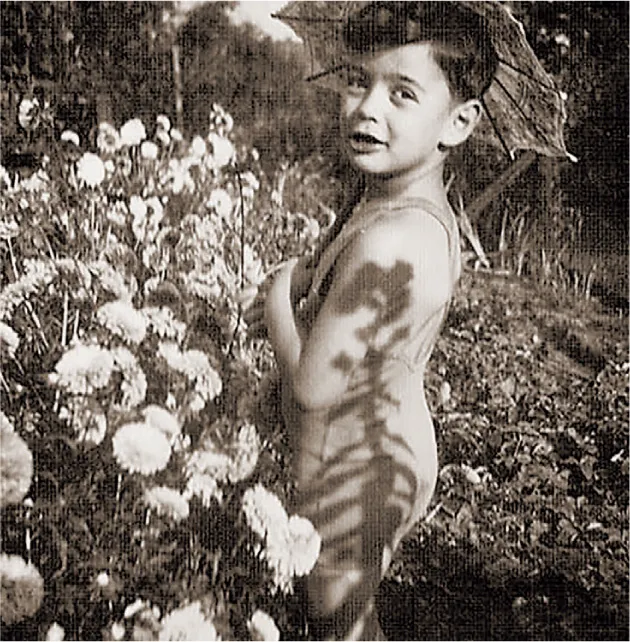

Time passed and my early childhood became more cheerful. Auntie Ruth,* my mother’s sister, took me on rowing trips across the Oder to our garden plot. Being in nature and sitting in a boat in the middle of the wide stream made great impressions on me. Even more so than being allowed to pick and devour the best tomatoes. There were also fun excursions to seaside resorts. I loved being around animals and plants and being surrounded by nature. But my favourite occupation was that of snail hunting: catching and collecting slimy little rolls that climbed up park walls.

This map shows the position of the German-Polish border in the 1930s.

My happy early childhood – Stettin 1933

When, in 1933, Hitler came to power, these leisurely and carefree times disappeared.

My father had been a doctor and surgeon in Stettin, but lost his practice due to the discriminatory laws, and we had to return to his hometown of Beuthen, a few hundred kilometres southeast of Berlin. Mother’s family, including Auntie Ruth and my grandparents, had moved to Berlin. And although I was only three then, I felt that I was constantly being left in the care of others, including my Aunt Irma* and our housekeeper, Magda.*

Beuthen was a mining town of some hundred thousand inhabitants with a strong Polish community. The German/Poland borders crossed suburbs, parks and even mining tunnels. Some of Beuthen’s streets had both German and Polish tramways running through them. People there spoke Polish in what was Germany, and German in what was Poland. When I returned from walks to the suburbs to Krakauer Strasse 1, a large four-storey building where we lived, I was never quite certain which of the two countries I had actually been through.

The town’s main square was even more confusing. To simple folk, it was ‘The Boulevard’. To more pedantic people, it was ‘Kaiser Franz Joseph Square’. But now, the new power in Beuthen decided it would become ‘Adolf Hitler Square’. And it was on that square that pure and loyal Germans swore allegiance to their new god.

If I had not been told off, I might have cheerfully joined them. For I rather liked this new cult. It meant flags, shiny police horses, colourful uniforms, torchlights and music. It was also free and easily accessible, meaning that I did not have to pester Dad to take me to a Punch and Judy show or be treated to an hour beside my auntie’s radio set. But I was chided for my improper enthusiasm towards this new presence in town. Instead I was given more pocket money, and, to avoid any further embarrassment to the family, an instruction to toe the family’s anti-Nazi line – whatever that meant to a four-year-old boy.

So, I obeyed. While the other youngsters on the square learned of their superior origin and destiny, my role would be that of the underdog.

Enjoying the beauty of nature – Beuthen, 1936.

Quickly, my life became a more secluded one. In the morning I was escorted to the nearby Jewish kindergarten. The afternoons were filled with solitary play or piano lessons under the tutelage of Father’s sister, Irma, a music teacher, who now lived with us.

I was supposed to have inherited much of Auntie Irma’s musical ability, but my rebellious temperament soon ruled out the chance of my becoming a slave to the giant, black ‘Bechstein’ piano. Instead, my talents were limited to gobbling up the fragrant apples that served as props to help me learn how the musical notes split into fractions. My interest in playing a musical instrument vanished, but my love of music, songs and remembering lyrics had just been ignited.

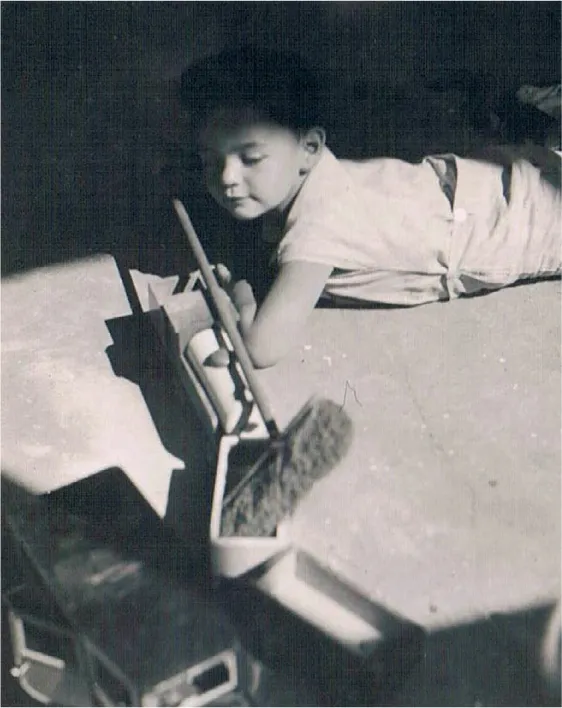

In 1936, aged six, I started at Beuthen’s Jewish school. Father, too, had once felt its cane, the punishment cellar and its strict Prussian discipline. He, likewise, had retaliated by scribbling and etching on the school’s benches.

Father’s teachers, already above retirement age, still taught there, and still could not afford anything more than white cheese sandwiches, which made them the subject of general ridicule. Aware of my family traditions, I tried to be a pleasant pupil, but never did more than was absolutely necessary.

We used both old textbooks and new Nazi textbooks. I remember Hitler’s birthday, 20 April, being a holiday. On this day, in accordance with some paragraph in the new educational laws, we gathered to hear recitations to the glory of the fatherland. The more insightful of our teachers, however, hinted that we would have no share in that glory.

My first day at school – Beuthen, 1936.

We learned that there was to be no equality. Our only weapon was pride. We wanted to compete with the new youth movements springing up across Germany. School outings turned into occasions to show off our disciplined marching, impressive singing and sporting prowess. But, one by one, these demonstrations were forbidden. Soon, we could not even retaliate to the stones being thrown at us in our schoolyard by the ‘Aryan’ boys outside. That would be a crime. Now we had become despised ‘Jew boys’. The only playground that remained safe for us was the park at the Jewish cemetery on Piekarska Strasse. We were actually glad to have a safe place to play in.

At my father’s urging, I joined a Zionist sports club, ‘Bar Kochba’.2 The training was strictly indoors, but the self-confidence it gave us was not so confined. There we learned about the principles of strength and heroism. Our newly acquired courage accompanied us everywhere.

One evening, a friend and I were making our way to the club and passed by the wintry synagogue square. We were greeted by a hail of snowballs. Then came the abusive insults. Behind the columns of the synagogue’s arcade, we caught glimpses of black Hitler Youth uniform coats sported by lads who seemed to be about our age.

Pride momentarily gained the better of our obligation to be docile underlings, and we gave chase. Our perplexed opponents had not reckoned on the sudden fury that overtook us. I grabbed one of them, threw him onto the snow and hit him repeatedly. When he started yelling, I had to retreat. His friends were nowhere to be seen, and darkness shrouded our little adventure in secrecy. That was to be my first and last chance to hit back openly.

Soon I grew more inquisitive about the world I lived in. We boys sneaked away to visit nearby coalmines, factories and railway installations. Our young minds were thirsty for knowledge.

The glaring white blast furnaces, the endless turning wheels of the pitheads, the enormous slag dumps, the ore-filled trolleys gliding along via sagging overhead steel cables – everything was teeming with activity. Trains in particular fascinated me. The squeaking industrial rail lines and the big black locomotives that came in from afar and relieved their exhaustion by blowing off clouds of smelly steam. It was all waiting to be analysed by our young minds, inspiring us with a desire to understand life. The world was still to be discovered by us.

There was so much for us to explore, despite the restrictions that were enforced on us.

While we roamed the town, curious to discover, Beuthen’s Hitler Youth were drilled, marched and taught to sing praises to the glory of their Führer. Not all of them possessed the required mental strength for this training. Some, seeing their future predestined by authoritarian rules, retreated into a state of misery. Others, with less delicate minds, worried about flat feet, corns and blisters, for these were much more realistic obstacles for inclusion in the ‘master race’.

A few times a year, Beuthen’s streets would come alive with processions. On Ascension Day and Easter, Catholic clerics – masters of pomp and ceremony – would swing incense on elaborately decorated floats, and carry their main attraction, the bishop, under a gold embroidered canopy. And on May Day, Hitler’s substitute for the 1 May holiday, fairs and bandstands would decorate Beuthen, and festive national costumes celebrating industrial and agricultural achievements would be on full display.

In contrast to the joyful sounds and bright colours of celebratory street scenes, increasingly, black jackboots could be heard marching to the tune of sober martial music. The Brownshirts4 contrived a new kind of procession: the night-time torchlight parade. Some ended with non-believers, Jews or similarly oppressed people, being beaten up.

My freedom was curtailed. I was ordered to stay home. There I watched these ‘shows’ from behind drawn curtains, with Mother explaining that these events were ‘not for our benefit’ and that I was to ‘avoid the streets and concentrate on indoor games’.

Unable to roam freely, I became more friendly with my school mates, inviting the more interesting ones home to play with my Meccano miniature railway set. Quickly, the family objected to my choice of friends.

‘Why must you bring these ill-mannered unkempt boys home?’ I was admonished. ‘Aren’t there enough respectable acquaintances of ours – doctors, lawyers, businessmen – whose children you could play with?’

But I was unconcerned with suitability or influence. My idea of having a good time demanded only new ideas, alertness, mutual respect and freedom. Thus, playmates chosen for me from good families never became good friends. Their knowledge of ‘the street’ was poor, their temperament was affected by their parents’ moods, and for every little thing they had to get permission from their maids.

Each year the festival of ‘Rejoicing with the Torah’5 was celebrated at our synagogue. Accompanied on the organ, children (dressed in their best suits and waving colourful flags) slowly followed the scrolls as they were carried around the temple. We were rewarded with the traditional handing out of sweets and chocolates.

Afterwards, we compared our treasures. My pockets were full, but I could see the disappointed faces of the other children. I was upset, as we should have all been rewarded.

Later, I asked my father about this, and his hesitant reply brought an unpleasant insight into my young mind that spoiled my fun. While most people gave generously to all the children, some people would single you out to take home their ‘visiting cards’ if your family had influence or social standing. Sweets. It seemed that Father was quite aware of who was distributing the chocolate bars or lollipops. Therefore, if you came from a family of have-nots, even a synagogue ceremony could make you aware of the fact.

One morning, the street underneath my window was humming with the noise of breaking glass, urgent footsteps and excited voices. It woke me up. Aware that it was time to get dressed for school, I got up and tugged at the belt of the roller shutter curtain. But to my surprise, it was only dawn. I peered over towards the pavement opposite our house.

One of the black Daimler cars that boys were so fond of was parked in front of the shoe shop. Our street was littered with shiny, black, brown and white boots, sandals and high-heeled women’s shoes and glass splinters. A team of uniformed Brownshirts were busy loading the car with all kinds of treasure. It was obviously a robbery.

Feeling rather like a successful detective, I ran to my parents’ room to tell them of this news. Visibly less glad about my disc...