![]()

Chapter 1

– – – – – – – – – –

THE BATTLEGROUND: BRAZIL

North American and Western European nations pay far more attention to one another than they do other parts of the world, with the possible exception of the Middle East, where their “attention” typically manifests as various forms of internal control and violent interference designed to maintain dominance over the region’s energy resources. But over the last several years, the West has devoted more attention to Brazil, with good reason.

In all circumstances, what happens in Brazil matters to the world, whether or not the world takes notice. Its size alone is one major reason. With a population of 213 million people, it is the sixth-most populous country on the planet, the second-largest in the hemisphere, and by far the most influential in Latin America. As one of the last countries to legally eliminate slavery, it both enjoys remarkable racial diversity and suffers from enduring systemic racism: whites are now a minority in a country where nonwhites remain largely excluded from most halls of power and wealth. Then there are the country’s natural assets, including its massive oil reserves, which helped make Brazil the world’s seventh-largest economy. And it is the custodian of the most environmentally and economically valuable forests in the world, found in the Amazon.

For all of those reasons, the country was a major focal point for the Cold War battles between the Soviet Union and the United States. In the 1950s and 1960s, Brazil struggled to avoid being swallowed by either of the two hostile superpowers, remaining generally neutral as it slowly built a measure of independence. Its 1946 constitution and the institutions it spawned became the basis for an imperfect yet burgeoning modern democracy, while the document came to serve as a regional model for guaranteeing modern civil liberties and democratic rights.

All of that came crashing down in April 1964, when right-wing factions of the Brazilian military, backed by multiple layers of support from the US Central Intelligence Agency and Pentagon, used physical force and intimidation, along with the threat of further violence, to oust the democratically elected center-left president. Amid hollow promises of a quick transition back to democracy, they imposed a twenty-one-year regime of military dictatorship that used murder, torture, and harsh repression to rule the country.

Three years prior to the coup, Brazilians had elected a ticket composed of the center-right Jânio Quadros as president and the center-left João Goulart as vice president. After Quadros resigned in August 1961—largely as a tactical bet, ultimately unsuccessful, that the population would rise up and demand his return, thereby strengthening him—Goulart assumed the presidency by constitutional mandate. When Brazilian oligarchs and military leaders resisted Goulart’s ascension to the presidency, asserting he was too left-wing, a compromise was reached in which Goulart would preside over a parliamentary system that, by design, significantly weakened the presidency. But in 1963, a national referendum that restored the presidency model overwhelmingly passed, serving as ratification of Goulart’s popular legitimacy and governance.

Contrary to the accusations made against him by Brazil’s elite classes, Goulart was nothing close to an actual communist. He was more of a soft, European-style socialist devoted to mild reforms of Brazil’s notoriously harsh systems that maintained massive wealth and income inequality. But at the hyper-paranoid peak of the Cold War in the 1960s, even an unthreatening center-left incrementalist, particularly one who had made some friendly gestures toward Moscow, was intolerable to Washington as president of the largest country in Latin America—a continent the United States, more or less continuously since the 1823 enactment of the Monroe Doctrine, has regarded as its “backyard,” subject only to its interference and control.

The Monroe Doctrine, written by then secretary of state and future president John Quincy Adams, was a declaration against European colonialism in Latin America (in exchange for a renunciation by the United States of colonialism in European spheres of interest). Despite such lofty language of noninterference, it was widely understood at the time of its enactment, and by US officials for the next two centuries, to be motivated not by anti-colonialist sentiments but their opposite: namely, the US government’s determination to exercise exclusive control over the continent nearest its homeland.

Any residual doubts about the core purpose of the doctrine were dispelled in 1895, when the United States objected to British behavior in a conflict with Venezuela over control of a nearby territory. President Grover Cleveland’s secretary of state, Richard Olney, threatened the United Kingdom with serious reprisals if it did not cease its coercive efforts, issuing one of the clearest understandings of the powers bestowed by the doctrine: “The United States is practically sovereign on this continent, and its fiat is law upon the subjects to which it confines its interposition.”

Three years later, the Monroe Doctrine again served as the express basis for US conflict with a European power over control of Latin America, this time in a much more serious way. In 1898, the US government supported Cuba in its war for independence against Spain; after winning the war and placing Cuba squarely within its sphere of control, the United States also “won” Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines from the Spanish.

Throughout the Cold War, US policymakers explicitly invoked the Monroe Doctrine as justification for their support in Latin America of coups, domestic repression, and other means of ensuring that governments friendly to US interests wielded power while those that did not paid the price. As recently as 2018, John Bolton, then President Donald Trump’s national security adviser, said the doctrine allowed the United States to overthrow the government of Venezuela if it so chose (and as Bolton advocated).

Under that well-established historical framework, US support for the violent 1964 overthrow of Brazil’s democratically elected center-left president, and the aid it provided to the military regime that followed, was nothing unusual. If anything, such a refusal to tolerate any form of leftism in Latin America’s largest country—even if it meant the imposition of despotism where democracy had been taking root—was virtually inevitable.

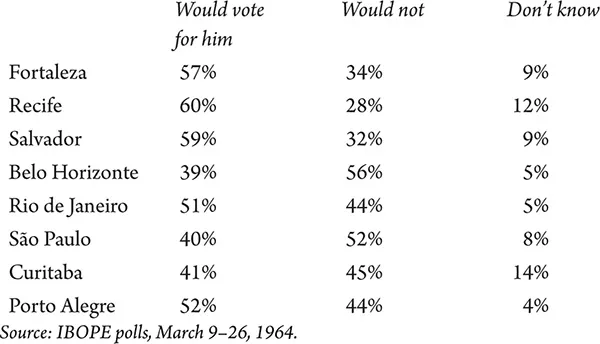

As he grew in confidence and stature following the 1963 referendum that fortified his power, President Goulart had increasingly angered the oligarchical class of both the United States and Brazil, the CIA, as well as Western institutions of capital that were lending Brazil money, including the International Monetary Fund. The three policies of President Goulart that had particularly provoked their ire addressed Brazil’s historically brutal wealth inequality: rent control, modest land reform programs, and a nationalization plan for some of Brazil’s oil fields. On the other hand, Goulart’s reforms had bolstered his popularity among the Brazilian people (whose opinions, after all, should have mattered to anyone purporting to favor “democracy”). Indeed, in 2014, Brazilian journalist Mário Magalhães unearthed polling data from the leading firm IBOPE from March 1964, which showed that President Goulart enjoyed widespread support in key regions around the country:

If President João Goulart could also run for president would you vote for him?

Under President Lyndon Johnson, the CIA, working with right-wing factions in the Brazilian military, successfully launched the military coup against the Goulart presidency, forcing the elected leader, under threat of house arrest and violence, to flee to Uruguay in April 1964. With Goulart out of the country, the military seized control and forced a scared and compliant Congress to legalize its coup.

Though the coup seemingly transpired in rapid and dramatic fashion—just a few days elapsed between US-backed Brazilian forces’ initial march on Rio de Janeiro and Goulart’s departure from the country—the administration of John F. Kennedy had determined two years earlier, in 1962, that Goulart could lead Brazil into Moscow’s orbit and even into communism, which warranted the covert plot against him. A 1963 visit to Goulart by Attorney General Robert Kennedy—designed to pressure the Brazilian president to become more pro-American and more capitalist-friendly, or face heightened economic sanctions—had been regarded in Washington largely as a failure. After that, covert CIA and Pentagon plotting with Brazil’s paramilitary forces against Goulart had intensified. The joint US–Brazilian military coup had thus been in the works for at least two years before it was finally executed.

In the coup’s aftermath, the US government vehemently denied widespread suspicions in the region that they had been involved. But classified documents that emerged at the end of that decade revealed the CIA’s role, and Washington was forced to publicly admit its backing of Goulart’s removal.

At first, State Department officials tried to minimize their involvement, casting the US role as one of mere communication with, and limited logistical aid for, the coup leaders. But as the years progressed and more and more documents from both countries emerged, US officials were forced to acknowledge a far greater role. As Vincent Bevins wrote in the New York Review of Books in 2018, “As part of Operation Brother Sam, Washington secretly made tankers, ammunition, and aircraft carriers available to the coup-plotters.” A mountain of other documents from both countries has subsequently been published—including diplomatic cables from the US ambassador in Brazil to the CIA, urging the provision of arms to the coup leaders, as well as Pentagon orders for deployments of US military assets to support them—that establish the central role of the United States as undisputed historical fact.

The Brazilian press, controlled at the time (as it is still) by a handful of oligarchical families, led by the burgeoning Globo media empire, celebrated the coup on its front pages as a noble “revolution” against a corrupt communist regime. As Bevins explains, “A huge part of Brazil’s political and economic elite supported the [coup] at the time,” including “all the major Brazilian newspapers except one.” Employing the standard, yet still bizarre, distortion pioneered by the US State Department, they heralded the forced removal of the elected president and imposition of military tyranny as a “restoration of democracy.”

The US media was equally effusive in praising the violent overthrow of President Goulart. Echoing the position of the State Department, the most influential US news outlets unflinchingly described the coup as a “pro-democracy revolution” against corruption, repression, and communism. Particularly supportive of the military generals was publisher Henry Luce’s then highly influential Time magazine, which assumed its traditional role of propagandizing for US foreign policy under the guise of journalism.

The Orwellian rhetorical framework used to depict the overthrow of democracy as a “restoration of democracy” is one that has been applied—before the 1964 coup in Brazil and since—in multiple countries to justify US intervention as a safeguarding of freedom, no matter how repressive the pro-US regime might be. In Cold War terms, because communism is the ultimate expression of repression, any attempts to combat it—no matter how despotic, contrary to popular will, or violent—are inherently noble and democratic.

In the post-Soviet era, Islam has replaced communism in this role. Current US alliances with the tyrannies of Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Egypt’s coup general Abdel Fattah al-Sisi are cast as unfortunate yet benign acts, designed to stave off worse (i.e., anti-American) elements from assuming power.

Crucial to this formula is the maintenance of illusory democracy—or symbolic gestures toward political liberalization—as a means to provide plausible deniability against accusations of despotism. When confronted with proof of repression, these regimes and their US patrons hype these “reforms” or nods to democracy as proof that the despots are moving, with the best of intentions, toward democratization, even if the progress is so gradual as to be undetectable. That was the tactic used by US media luminaries, led by New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman and Washington Post columnist David Ignatius, to create a myth of bin Salman as a crusading pro-democracy reformer—efforts that came crashing down on them only when the Saudi crown prince was caught ordering the murder and chopping up of Ignatius’s Post colleague Jamal Khashoggi. Similarly, al-Sisi came to power in Egypt after a violent military coup that overthrew the country’s first democratically elected president, Mohammed Morsi. Even as al-Sisi brutally cracked down on all dissent following the 2014 putsch, US officials, including then secretary of state John Kerry, praised the coup leaders for “restoring democracy.”

This same framework was used to justify and celebrate the Brazil coup as a pro-democracy revolution. Within the State Department and in the US press, President Goulart was imaginatively transformed from an incrementalist, center-left reformist who had, one year earlier, received an overwhelming democratic mandate (even while infuriating the actual left with accommodations to capitalism and oligarchy), into a communist tyrant whose removal was imperative for the salvage of Brazilian freedom and democracy.

– – – – – – – – – –

After forcing President Goulart to flee and installing themselves in power, Brazil’s military coup leaders quickly complied with a key condition of US support for the coup: the “opening up” of Brazilian markets to international capital. Within two years of the 1964 coup, roughly half of Brazil’s major industries were owned by foreign interests.

Domestically, what followed was a predictable and familiar nightmare. The military regime’s first act was a decree entitled First Institutional Act (AI-1), which suspended most of the rights guaranteed by the 1946 constitution, paving the way for increasingly violent and repressive tactics. Supported, trained, and armed by both the United States and the United Kingdom, the dictatorship imprisoned dissidents without trial, murdered leftist journalists, rounded up university students, tortured critics and activists, summarily removed disobedient senators and members of congress, indefinitely suspended basic civil liberties, and proclaimed the right to ignore judicial orders. In just a few years, the coup generals had consolidated their stranglehold over political and cultural life.

In 1968, with the regime’s Fifth Institutional Act (AI-5), its leaders arrogated unto themselves virtually absolute control, rendering all other democratic institutions—the courts, Congress, and the media—little more than facades whose real function was unquestioning fealty to the generals. Following the well-established Cold War formula for masking repression, the military dictatorship continued to adhere to empty legalities to provide plausible deniability. The ruling Brazilian general assumed the presidency only after being “elected” by Congress (which the generals controlled on account of their power, aggressively invoked, to summarily remove any noncompliant members). They also avoided having one identifiable strongman, such as Chile’s Augusto Pinochet or Paraguay’s Alfredo Stroessner (both later praised by President Jair Bolsonaro), serve as the symbol of repression; instead, every few years they passed power from one banal, faceless general to the next.

In order to create cover for their autocratic rule, Brazil’s government also followed the well-worn script of allowing a controlled opposition. A decree enacted shortly after the coup established two parties: one was the ruling party, the National Renewal Alliance (ARENA), while the other was the supposed opposition, the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB). But allowing an opposition party while maintaining the power to prevent it from taking office, as ARENA did, is fraud.

Once it became apparent that the regime had no intention of returning power to civilian democratic control, a vibrant—and sometimes violent—left-wing resistance arose. This resistance spanned the spectrum, from armed communist guerillas who carried out high-profile kidnappings in order to free imprisoned comrades (such as the 1969 abduction of US ambassador Charles Burke Elbrick), to peaceful socialist activists who sought to use whatever minimal freedoms they possessed to agitate for the return of free and direct elections.

But each minimal advance of the resistance—whether peaceful or armed—was met with increasing violence. Anyone suspected of having ties to, or even harboring sympathy for, the armed resistance was abducted, imprisoned without charges, routinely subjected to brutal methods of torture (which the United States, United Kingdom, and France trained Brazilian interrogators to use), and often killed. Famous artists, writers, and musicians who were critics of the military rulers were arbitrarily imprisoned and then forced into exile. Newspapers that exceeded the bounds of permitted dissent were summarily closed, and their journalists and editors imprisoned or killed.

Among those who took up arms against the military dictatorship was a young student and newspaper editor named Dilma Rousseff. In 1970, at the age of twenty-three, she was kidnapped from a São Paulo restaurant where she had gone to meet a friend, imprisoned without charges, and tortured for twenty-one days, using standard regime interrogation methods such as beating her palms and soles with paddles, punching her, placing her in stress positions, and using electric shocks. Without anything resembling a fair trial, she was imprisoned for more than two years. Thirty-eight years later, in 2010, Dilma, by then a sixty-three-year-old center-left pragmatist, economist, and technocrat in the Workers’ Party, was elected as Brazil’s first-ever female president.

Despite how widely despised the military dictatorship became, its powers of censorship made successful challenge to its authority virtually impossible. Media loyal to the regime disseminated an endless stream of propaganda that helped render the population largely submissive—especially Globo, whose founder, João Roberto Marinho, built one of the most dominant media outlets in the world through his servitude to the regime, in the process becoming one of the world’s richest men. (Marinho’s three sons—all billionaires—continue to enjoy the fruits of their family’s service to the dictatorship through their ongoing control over Globo.)

Only in the mid-1970s, when multiple horror stories broke through the regime’s wall of censorship and reached the general population, did Brazilians’ demands for restoration of their civic rights and democratic freedoms finally become too powerful to suppress. Throughout the late 1970s and into the early 1980s, as street protests grew, the military regime began to realize that it could no longer maintain its control. Finally, in 1985, pro-democracy citizen movements forced the formal process of redemocratization, when indirect elections were held that brought a civilian into the presidency for the first time since 1964. A new constitution, enacted in 1988, reinstated core civil liberties that are the hallmark of any democracy, including robust protections for free speech and a free press that exceed even those offered by the First Amendment to the US Constitution. And in 1989, Brazilians directly elected their first president since the 1961 election, marking the return of democracy.

Many historians identify the tipping point that led to the toppling of the regime as the 1975 murder of Vladimir Herzog, a leftist Jewish journalist who had fled to Brazil in the 1940s after German fascists seized power in his Croatian hom...