eBook - ePub

Debating Cultural Hybridity

Multicultural Identities and the Politics of Anti-Racism

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

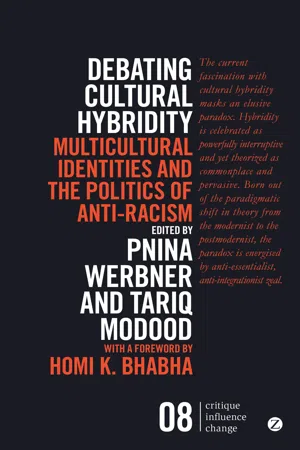

Debating Cultural Hybridity

Multicultural Identities and the Politics of Anti-Racism

About this book

Why is it still so difficult to negotiate differences across cultures? In what ways does racism continue to strike at the foundations of multiculturalism? Bringing together some of the world's most influential postcolonial theorists, this classic collection examines the place and meaning of cultural hybridity in the context of growing global crisis, xenophobia and racism. Starting from the reality that personal identities are multicultural identities, Debating Cultural Hybridity illuminates the complexity and the flexibility of culture and identity, defining their potential openness as well as their closures, to show why anti-racism and multiculturalism are today still such hard roads to travel.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Debating Cultural Hybridity by Pnina Werbner, Tariq Modood, Pnina Werbner,Tariq Modood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

INTRODUCTION: THE DIALECTICS OF CULTURAL HYBRIDITY

PNINA WERBNER

THE POWER OF CULTURAL HYBRIDITY

The current fascination with cultural hybridity masks an elusive paradox. Hybridity is celebrated as powerfully interruptive and yet theorized as commonplace and pervasive. Born out of the paradigmatic shift in theory from the modernist to the postmodernist, the paradox is energised by anti-essentialist, anti-integrationist zeal.

The power of cultural hybridity – one side of the paradox – makes sense for modernist theories that ground sociality in ordered and systematic categories; theories that analyse society as if it were bounded and ‘structured’ by ethical, normative dos and don’ts and by self-evident cultural truths and official discourses. In such theories, it makes sense to talk of the transgressive power of symbolic hybrids to subvert categorical oppositions and hence to create the conditions for cultural reflexivity and change; it makes sense that hybrids are perceived to be endowed with unique powers, good or evil, and that hybrid moments, spaces or objects are hedged in with elaborate rituals, and carefully guarded and separated from mundane reality. Hybridity is here a theoretical metaconstruction of social order.

But what if cultural mixings and crossovers become routine in the context of globalising trends? Does that obviate the hybrid’s transgressive power? And if not, how is postmodernist theory to make sense, at once, of both sides, both routine hybridity and transgressive power? Even more, what do we mean by cultural hybridity when identity is built in the face of postmodern uncertainties that render even the notion of strangerhood meaningless? When culture itself, all cultural categories, are – as Hans-Rudolf Wicker and Alberto Melucci argue – reflexively in doubt, unstable and lacking cognitive faith or conviction? How do the subjects of (post)modern nation-states respond to such ambivalences and the sheer efflorescence of cultural products, ethnicities and identities? This is a central question in postmodernist theory, and one that the contributors to this volume directly address.

The paradox leads us to ask about the limits of cultural hybridity, demarcated not only by hegemonic social formations but by ordinary people. What are the forces, Jonathan Friedman asks, that generate antihybrid, essentialising discourses stressing cultural boundededness, ethnicity, racism or xenophobia? And how are we to theorise the ambivalences and multiplicities contained in these forces? Why do strangers continue to pose a threat, despite the fact that the very meaning of strangerhood might seem to be elusive and meaningless in what Zygmunt Bauman defines as an age of ‘heterophilia’?

Modernist hybridity theory made its heuristic gains on very different frontiers. Starting from an assumption about cosmic and social ordering, Claude Lévi-Strauss analysed tricksters as ambiguous and equivocal mediators of contradiction (1963); Victor Turner explored the anti-structural properties of liminality and hybrid sacra (1967); while Mary Douglas recognised the dangerous or beneficial powers of exchange inherent in anomalous conflations of otherwise distinct categories (1966; 1975).1 Starting from a perspectival position within society, these outstanding contributions to modernist anthropology stressed the capacity of hybrid symbolic monstrosities to challenge the taken-for-granteds of a local cultural order, and thus to recover a critical cultural self-reflexivity. Their theoretical stance allowed them to explain why dangerous mixings were culturally marked and hedged with taboos.

Along with that, modernist hybridity theory looked to sites of resistance and exclusion, as in Foucault’s analysis of heterotopic spaces (Foucault 1986). Similarly, Barthes (1972), Bourdieu (1984) and Bakhtin (1984) analysed popular mass culture and carnival as subversive and revitalising inversions of official discourses, high-cultural aesthetic forms or the exclusive lifestyles of dominant elites. Such popular mixings and inversions, like the subversive bricolages of youth cultures analysed by Hebdige (1979), are ‘hybrid’ in the sense that they juxtapose and fuse objects, languages and signifying practices from different and normally separated domains and, by glorifying natural carnality or ‘matter out of place’, challenge an official, puritanical public order. Indeed, the ordering tendencies of modernity are, Bauman argues, the key to understanding intolerance towards ‘strangers’ in the modern nation-state, leading either to their expulsion/elimination or to their assimilation (Bauman 1989; see also this volume, Chapter 3). This also explains why the defence of hierarchy and elite privilege in colonial settler societies was buttressed, Papastergiadis shows, by a pervasive fear of ‘racial’ hybridity.

From a postmodern perspective, it might seem self-evident that essentialising ideological movements need to be countered by building cross-cultural and multi-ethnic alliances. But cross-cultural or gendered politics, the politics of anti-racism or of transversal alliances, turn out to be fraught with the very same sorts of difficulties that generate the contemporary dual forces of hybridity and essentialism in the first place. Rather than being open and subject to fusion, identities seem to resist hybridisation. The result, Nira Yuval-Davis argues, is that the creation of new oppositional alliances aiming to transcend differences must contend with the resistance of activists to a fusing of their identities and subject positions. What makes for that resistance, and why is it so difficult, Alastair Bonnett and Michel Wieviorka ask, to be an anti-racist? Why is cultural racism a pervasive force, as Tariq Modood claims, and to what extent do ethnic demotic discourses that fuse identities coexist with essentialist discourses that deny such fusings – a question explored by Gerd Baumann. We need to interrogate, Werbner argues, the schismogenetic forces that undermine coexistence, however uncertain and fragmentary, and precipitate polarising essentialisms.

This subject – the attack on or the possibility of transcending and negotiating cultural difference – was the theme of the conference for the present volume. The title of the conference, ‘Culture, Communication and Discourse: Negotiating Difference in Multi-Ethnic Alliances’, was open enough to allow participants to raise concerns that seemed most pressing at the present theoretical moment. These turned out to be the place and meaning of cultural hybridity in the context of growing global uncertainty, xenophobia and racism. It is significant that all the contributors are European sociologists and social anthropologists. In Europe, hybridisation and xenophobia seem at first glance to be conflicting political forces. Yet counterposed to the destructive power of xenophob ia or fetishised ‘culture’ are also the cultural claims made by minorities and small European nations to be recognised as different, and to retain their right to practise distinctive cultures and religions.

How are we to make sense of such claims when the very concept of culture disintegrates at first touch into multiple positionings, according to gender, age, class, ethnicity, and so forth? As Culture evaporates into a war of positions, we are left wondering what it might possibly mean to ‘have’ a cultural ‘identity’. In the present deconstructive moment, any unitary conception of a ‘bounded’ culture is pejoratively labelled naturalistic and essentialist. But the alternatives seem equally unconvincing: if ‘culture’ is merely a false intellectual construction, a manipulative invocation by unscrupulous elites or a bricolage of artificially designed capitalist consumer objects – a feature of late capitalism stressed by John Hutnyk – where does the destructive or revitalising power of cultural identities and hybridities come from?

The attempt to grapple with these questions and the ambivalences they imply is what makes the present debate so compelling and, indeed, so novel and fresh. We have moved beyond the old discussions that start from certain identities, communities and ordered cultural categories into unchartered theoretical waters. Inadequate, too, are the old modernist insights into the nature of liminality, the place and time of betwixt- and-between, of carnivals, rituals of rebellion and rites of cosmic renewal, or of boundary-crossing pangolins, ritual clowns, witches and abominable swine. We need to incorporate these insights into a broader theoretical framework which aims to resolve the puzzle of how cultural hybridity manages to be both transgressive and normal, and why it is experienced as dangerous, difficult or revitalising despite its quotidian normalcy.

Before attempting to trace what the contours of an emergent theory of hybridity that is postmodern, post-colonial and late-capitalist might be, I want to draw upon a crucial distinction made by Bakhtin. This distinction helps to sweep away much unnecessary confusion plaguing postmodernist discussions of hybridity. It also creates a bridge to earlier modernist approaches, I believe, and thus enables us to draw on the insights developed by these approaches in our attempt to explain why, on a culturally hybrid globe, cultural hybridity is still experienced as an empowering, dangerous or transformative force. Conversely, we can begin to consider why borders, boundaries and ‘pure’ identities remain so important, the subject of defensive and essentialising actions and reflections, and why such essentialisms are so awfully difficult to transcend.

INTENTIONAL HYBRIDITIES

In his work on the dialogic imagination, Bakhtin makes a key distinction between two forms of linguistic hybridisation: unconscious, ‘organic’ hybridity and conscious, intentional hybridity. For Bakhtin, hybridisation is the mixture of two languages, an encounter between two different linguistic consciousnesses (1981: 358). Organic, unconscious hybridity is a feature of the historical evolution of all languages. Applying it to culture and society more generally, we may say that despite the illusion of boundedness, cultures evolve historically through unreflective borrowings, mimetic appropriations, exchanges and inventions. There is no culture in and of itself. As Aijaz Ahmad puts it, the ‘cross-fertilisation of cultures has been endemic to all movements of people … and all such movements in history have involved the travel, contact, transmutation, hybridisation of ideas, values and behavioural norms’ (Ahmad 1995: 18). At the same time – and this amplifies Bakhtin’s point – organic hybridisation does not disrupt the sense of order and continuity: new images, words, objects, are integrated into language or culture unconsciously. Yet despite the fact, he says, that ‘organic hybrids remain mute and opaque, such unconscious hybrids … are pregnant with potential for new world views’ (ibid.: 360).

Hence organic hybridity creates the historical foundations on which aesthetic hybrids build to shock, change, challenge, revitalise or disrupt through deliberate, intended fusions of unlike social languages and images. Intentional hybrids create an ironic double consciousness, a ‘collision between differing points of views on the world’ (ibid.; see also Young 1995: 21–5). Such artistic interventions – unlike organic hybrids – are internally dialogical, fusing the unfusable.

Bakhtin’s distinction is useful for theorising the simultaneous coexistence of both cultural change and resistance to change in ethnic or migrant groups and in nation-states. What is felt to be most threatening is the deliberate, provocative aesthetic challenge to an implicit social order and identity, which may also be experienced, from a different social position, as revitalising and ‘fun’. Such aesthetic interventions are thus critically different from the routine cultural borrowings and appropriations by national and ethnic or migrant groups which unconsciously create the grounds for future social change. This is a feature of discourse highlighted by Gerd Baumann: while demotic discourses deny boundaries, the dominant discourses of the very same actors demand that they be respected.

The danger that the aesthetic poses for any closed social universe with a single monological, authoritative, unitary language is that of a heteroglossia ‘that rages beyond the boundaries’ (Bakhtin 1981: 368). Lotman’s ‘semiosphere’ is an attempt to theorise this heteroglossia in centre–periphery terms (Papastergiadis). Intentional heteroglossias relativise singular ideologies, cultures and languages. Organic hybridisation casts doubts on the viability of simplistic scholarly models of cultural holism.

Several of the contributors to this volume (Wicker, van der Veer, Baumann) reflect on the limitation of earlier anthropological models of bounded cultures and societies. Radical critics of anthropology even suggest, according to Wicker, that culture as a complex whole perpetuates earlier notions of race. These are outlined here by Papastergiadis in his discussion of the painful reflections of Octavio Paz and Gilberto Freyre on Mexican and Brazilian notions of hybrid contamination. Critics of holistic cultural models cite New Right claims about the intrinsic incommensurability of cultures as proof that multiculturalist notions that start from ideas about the homogeneity (and hence boundedness) of culture are dangerously essentialist. As several contributors stress, such assumptions reify ‘culture’ in substantivist terms, as object, in a logic that seems, on the surface at least, inimical to individual and universal rights.

There is, however, a tremendous irony in the historical revisionism that equates anthropological theories of cultural holism with racism: both Durkheim’s society and Boas’s culture were, after all, powerful analytical tools used to disprove evolutionary, racist theories. Notwithstanding the often bitter anthropological disagreements between structuralists and relativists, their common purpose was (and is) to demonstrate that the apparently bizarre, primitive or barbaric beliefs and customs of the ‘natives’ were rational, moral and meaningful, if they were seen in context. Second, they aimed to prove that cultures had value in their own terms, were vital for human diversity, and hence also had a rightful claim not to be destroyed in the name of Europe’s civilising mission.

The irony of anthropology’s postmodernist critique of cultural or social holism is compounded by its enunciation at the present poststructuralist moment, marked, above all, by its sceptical denial of even the possibility of universal rationality, truth and morality (Friedman, Bauman). We may say that rather than being racist, Lévi-Strauss’s or Durkheim’s ideas about the socially embedded nature of truth, as developed by modernist anthropologists, anticipated poststructuralist claims that knowledge and truth are the authoritative effects of language games, discourses and interpretive communities. James Clifford puts the latter position sharply when he argues that universal ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- About the Editors

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface to the critique influence change edition

- Preface to the first edition

- 1 Introduction: The Dialectics of Cultural Hybridity

- Part One Hybridity, Globalisation and the Practice of Cultural Complexity

- Part Two Essentialism Versus Hybridity: Negotiating Difference

- Part Three Mapping Hybridity

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index