eBook - ePub

The Oasis Papers 6

Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project

- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Oasis Papers 6

Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project

About this book

The Dakhleh Oasis Project is a long-term holistic investigation of the evolution of human populations in the changing environmental conditions of this isolated region in the Western Desert of Egypt. The Project began in 1978 and has combined survey and excavation to collect an extensive range of geological, environmental and archaeological data which covers the last 350, 000 years of human occupation. This latest volume in the Monograph series publishing the results of the Project contains 41 papers with a wealth of new research and significant discoveries, from Prehistory, through Pharaonic and Roman times to the Christian period.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Provisions for the Journey: Food Production in the ‘bakery’ area of ‘Ain el-Gazzareen, Dakhleh Oasis

Amy J. Pettman, Ursula Thanheiser and Charles S. Churcher

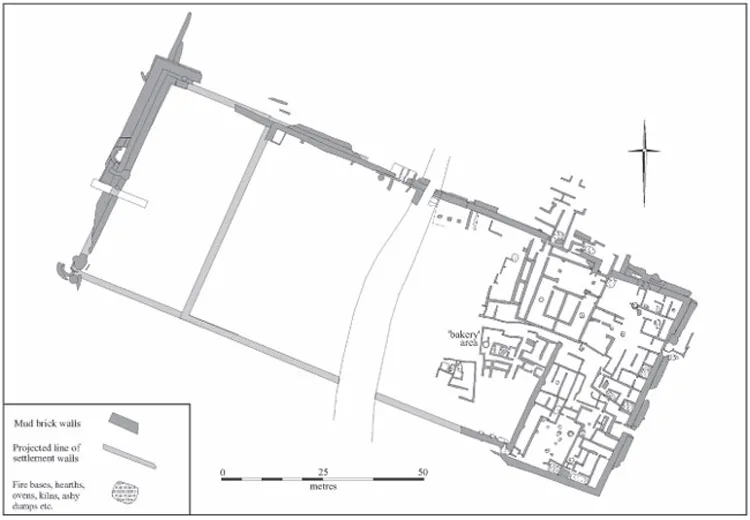

‘Ain el-Gazzareen is an extensive site located on the western fringe of the Dakhleh Oasis. In this area, the natural water supply has been more reliable than in other parts of the oasis, and the groundwater table has been close to the surface resulting in damp soil conditions, thereby supporting a comparatively varied flora. The site has been excavated by Anthony J. Mills since 1995. It is dominated by a rectangular mud-brick enclosure measuring approximately 125m by 55m (Mills and Kaper 2003, 125) (Figure 1). The site dates to the Old Kingdom; analysis of the ceramic material shows that the occupation encompassed at least Dynasties V–VI, with the initial establishment perhaps even as early as Dynasty IV (Pettman, this volume). In the first few years of excavation, the area within this enclosure known as H13/I13 was excavated (Mills 1995) (Figure 2). This area lies close to the original short eastern wall of the enclosure and was probably constructed during the initial development of the site. These excavation squares cover an area of approximately 10 × 15 m (Mills 1997–1998, 17).

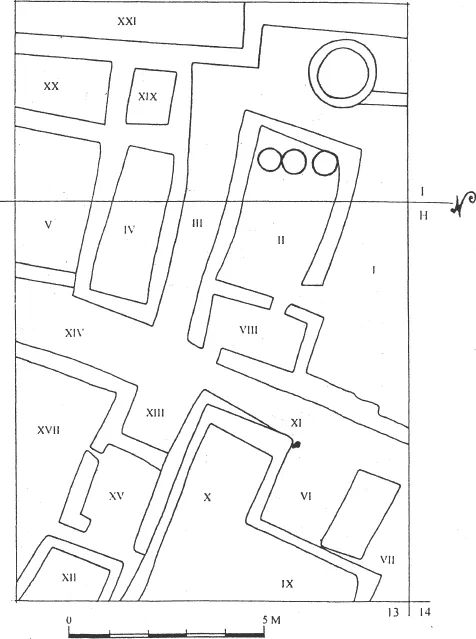

Twenty-one rooms or spaces are included within this area, though of those only seven are located entirely within H13/I13 and only five are completely contained by mud-brick walls. Several of these rooms preserved a packed mud-brick floor, though this feature was not discernible in all rooms, and Room V demonstrated two different floor levels, one above the other.

Mills (1995, 64) identified H13/I13 as a bakery area. This identification was based on several factors: a significant number of heavy, straw-tempered bread moulds of typical Old Kingdom form (Mills 1995, 64; Mills 2002, 76); a large quantity of ash (Mills 1995, 62); a high occurrence of grains and rachises of barley (Hordeum vulgare) and grains and spikelet forks of emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccum) (Mills 2002, 76); and a circular structure in Room I which appears to have served as a silo (Mills 1995, 64). Three very large ceramic vessels were also discovered at the western end of Room II (Figure 2), which Mills (1995, 64) suggested functioned as permanent fixtures for storage of foodstuffs.

Following the initial examination of this material shortly after its excavation, little detailed analysis occurred and no further investigation into the function of this area was undertaken until recently (Pettman 2008; 2011). A large variety of botanical and faunal remains was recovered from the excavations which has the potential to yield a great deal of information regarding the nature of activity, both within the area of H13/I13 and at ‘Ain el-Gazzareen as a whole. An extensive ceramic assemblage was recovered from the excavation of this area.

The aim of this article is, therefore, to present the archaeobotanical, archaeozoological and ceramic material from H13/I13 in order to examine the rationale for the initial identification of this area as a bakery, and to show that some revision of this is now necessary. It will also provide key data regarding the subsistence strategies of the Egyptian residents of the oasis during the Old Kingdom, allowing a better understanding of how the new ‘colonists’ of this region used the resources at their disposal. The determination of the function of this area will contribute much to our understanding of the role of ‘Ain el-Gazzareen in light of the Old Kingdom occupation of Dakhleh Oasis; this article will thus attempt to show that the evidence from H13/I13 suggests that the function of this site must be connected to trade and travel passing through Dakhleh Oasis from the Nile Valley, and perhaps also Farafra Oasis, further into the Western Desert.

The Archaeobotanical Evidence

Egyptians from the Nile Valley first permanently settled in Dakhleh Oasis during the Old Kingdom, possibly from Dynasty IV onwards (Hope and Pettman, this volume). They did not adopt the hunting and herding way of life of the indigenous Sheikh Muftah people (Thanheiser 2008, 151) but brought with them a subsistence strategy hitherto unknown in the area: agriculture. However, the oasis environment with its lack of annual Nile floods was challenging. The climate had more-or-less reached its present state of hyperaridity, and very little rain fell at irregular intervals, thus rendering rain-fed agriculture impossible. The surrounding area had already lost most of its plant cover and feeding livestock by grazing outside the oasis was no longer possible. All life therefore depended on groundwater reaching the surface along natural vents or as springs. At the time, no effective water-lifting devices were available and therefore wells only served to meet the personal needs of the inhabitants and eventually to water small garden plots. Agriculture depended entirely on careful management of springs. The easiest way to provide sufficient amounts of water for irrigation would have been to build dams around spring eyes in a collective effort in order to raise the point of discharge and create the necessary gradient for gravity propelled irrigation. This ‘Egyptian’ subsistence strategy, i.e., irrigation-based agriculture, was applied successfully in the oasis and from the very beginning of the Egyptian occupation all crops known in the Nile Valley were also present in Dakhleh. In an environment where plant growth is dependent to a large extent on artificial water supply, field crops serve a dual purpose, as they have to feed humans and beast alike.

Figure 1 Plan of ‘Ain el-Gazzareen; area H13/I13 (‘bakery’) occurs in the south-eastern corner, just west of the original (inner) eastern wall (courtesy of A. J. Mills).

Figure 2 Plan of the area H13/I13; the location of Rooms XVI and XVIII are not marked on this plan and are unknown (after Mills 1995, 63).

Material and Methods

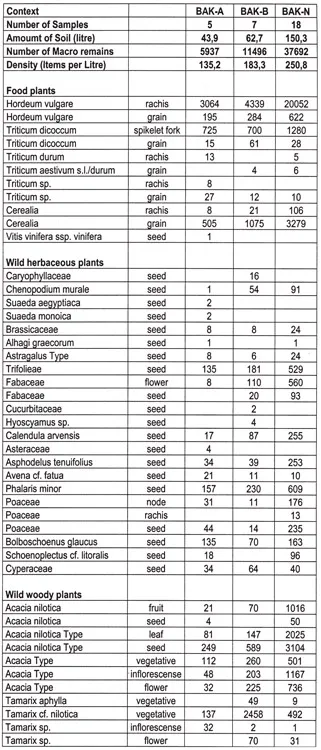

Several parts in the area yielded large, ashy deposits; 30 random matrix samples, varying in volume from 3.7 to 13.5 litres, were taken. According to their position in relation to floors these samples can be grouped as follows: 5 samples from floors or above (BAK-A), 7 samples from below floors (BAK-B), 18 samples from areas where no floor was present (BAK-N).

The biological remains were extracted from the soil by electrostatic means by which the matrix was split into ‘predominantly organic’ and ‘inorganic’ fractions (Thanheiser 1995); the smallest mesh diameter was 0.5 mm. From the organic fraction, the plant remains were then isolated manually using a dissecting microscope and identified using the writer’s personal reference collection. Scientific nomenclature for wild plants follows the Flora of Egypt (Boulos 1999 –2005). For cultivated plants the terms known in archaeology are used. Very rich organic fractions were divided with a riffle box and only a part of the sample (usually half or a quarter) was analysed. The figures given in the tables referred to below thus represent calculated numbers. Each item was counted as one piece irrespective of its actual completeness. Only the number of spikelet forks represents calculated whole items. The inorganic fraction was screened for possible escapes.

Only charred plant remains are present. This mode of preservation is the result of a burning event by which the organic material was reduced to almost pure carbon. Charred plant remains in domestic contexts can usually be linked to food preparation, the use of plants as fuel or the accidental burning of structures. Although the density of plant remains in the bakery is much higher than in other areas of ‘Ain el-Gazzareen, the number of recovered taxa is rather low. This is a well-known phenomenon at sites with exclusively charred plant remains and is a direct result of the burning event: mainly dense, compact items survive the heat in charred form. In addition, charring and subsequent taphonomic processes often cause distortion of propagules and a loss of the seed or fruit coat (testa or pericarp) with its diagnostic features. Therefore charred plant remains often cannot be identified to species level. In contrast to other (later) sites in the Dakhleh Oasis, desiccated plant remains are not present in `Ain el-Gazzareen, reflecting the damp conditions at the site.

A calculated total of 55,125 identifiable macro remains was recovered. In addition, 4.5% of the botanical remains are unidentifiable material, comprising mainly minute vegetative items such as fragments of twigs, stems and leaves which do not appear in the lists. The identified macro remains can be grouped into three categories: food plants, wild herbaceous plants and wild woody plants (Table 1). Furthemore, 1330 pieces of charcoal were identified (Table 2).

Table 1 Plant macro remains.

Table 2 Charcoal.

| Number of samples | 30 |

| Chenopodiaceae | 2 |

| Acacia nilotica | 153 |

| Acacia tortilis ssp. raddiana Type | 2 |

| Acacia sp. | 95 |

| Faidherbia albida | 21 |

| Tamarix sp. | 512 |

| Calotropis procera | 54 |

| Leptadenia pyrotechnica | 3 |

| Indet. root | 1 |

| Indet. twig | 1 |

| Indet. | 486 |

| Total | 1330 |

Food Plants

Two species of cereals are present, emmer wheat, Triticum dicoccum, and barley, Hordeum vulgare. Both are represented by chaff and grains. Identification of emmer wheat is based on the very characteristic rachis segments, the spikelet forks. The grains are slim in dorsal view, rounded at the distal end and pointed at the embryo end; the ventral side is slightly concave or flat; in lateral view they are slightly humped. Some well-preserved grains have longitudinal furrows representing impressions of the glumes. In addition, a few rachis segments and grains representing hard wheat, Triticum durum, are present. Emmer wheat was the principal wheat crop in Egypt since the introduction of agriculture, and the current view is that it maintained this status throughout the Pharaonic period, but was gradually replaced by hard wheat from Ptolemaic times onwards (e.g., Cappers 2006, 130; van der Veen 2011, 141). Occasional finds of remains of free-threshing wheat have been reported in Egypt from contexts dating back to the Predynastic Period (de Vartavan and Asensi Amoros 1997), but are considered to represent weeds in emmer crops.

The grains of barley are spindle-shaped both in dorsal and lateral view. Ridges on the surface represent the remains of glumes. No asymmetrical grains are present. The rachis segments are straight and taper outwards at the top. Pedicels and glumes are not present. Although there is no convincing archaeobotanical evidence, it is likely that the barley remains represent six-row hulled barley, the principal barley crop in Egypt since Predynastic times. In ‘Ain el-Gazzareen barley is by far the dominant cereal plant. It needs less water than emmer wheat, has lower demands concerning soil quality and can also grow on slightly saline soil. It is therefore often the crop of choice on land newly reclaimed for agriculture.

Emmer wheat and barley are hulled and the grains are not released from the glumes by threshing. These glumes are unsuitable for human consumption but offer a good protection of the grain against mould. Therefore removal of the glumes by wetting and subsequent pounding is often carried out on a day-to-day basis. The by-products of this step in the cereal processing sequence such as chaff (rachises, glumes and awns) and weeds not extracted in previous crop processing stages are often used as fodder or fuel, and therefore have a high chance of being incorporated in the charred plant assemblage.

With the exception of one grape pip, Vitis vinifera ssp. vinifera, from a floor sample, no other cultivated plants are present in the bakery. Other areas of the site, however, also yielded lentil (Lens culinaris) and flax (Linum usitatissimum).

Wild Herbaceous Plants

This group is dominated by Fabaceae (most notably Trifolieae and other small seeded legumes), Poaceae (mainly Phalaris minor), and by Cyperaceae (Bolboschoenus glaucus and Schoenoplectus cf. litoralis). Other important components of the assemblage are Calendula arvensis, Asphodelus tenuifolius and Chenopodium murale. Together they represent 8–11% of the recovered plant assemblage and almost 100 percent of the wild herbaceous plants.

The tribe Trifolieae comprises several genera which are widely distributed in ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Editors’ Preface

- Contents

- Conference Programme

- Major Archaeological Sites in Kharga Oasis and Some Recent Discoveries by the Supreme Council of Antiquities

- Wanderers in the Desert: The North Kharga Oasis Survey’s Exploration of the Darb ‘Ain Amur

- Demotische und kursivhieratische Ostraka aus Mut al-Kharab

- Cultural Heritage Management of the Archaeological Resources of the Deserts of Egypt

- The Culture of the Oases: Late Neolithic Herders in Farafra, A Matter of Identity

- Geomatics Resources for Archaeological Survey in Desert Areas – Some Prospects from Farafra Oasis, Egypt

- Beyond the Shale: Pottery and Cultures in the Prehistory of the Egyptian Western Desert

- The Gebel Souhan Problem: Local Innovation in the Middle Stone Age?

- Early Craftsmen of the Desert. Traces of Predynastic Lithic Technology at Farafra during the Mid-Holocene

- Levallois Lithics on a Middle Stone Age Playa: Finds at Bir el-Obeiyid, Northern Farafra Depression, Egypt

- Wadi Sura and the Gilf Kebir National Park: Challenge and chance for archaeology and conservation in Egypt’s south-west

- The Khargan Industry Revisited

- Technique and Content in the Rock Art of the Libyan Fezzan: some Saharan Stereotypes

- Egyptian Connections with Dakhleh Oasis in the Early Dynastic Period to Dynasty IV: new data from Mut al-Kharab

- Epigraphic Evidence from the Dakhleh Oasis in the Late Period

- An Old Kingdom Trading Post at ‘Ain el-Gazzareen, Dakhleh Oasis

- The Date of the Occupation of ‘Ain el-Gazzareen based on Ceramic Evidence

- Provisions for the Journey: Food Production in the ‘bakery’ area of ‘Ain el-Gazzareen, Dakhleh Oasis

- Ptolemaic Period Pottery from Mut al-Kharab, Dakhleh Oasis

- An Agricultural Account from the Gemellos Archive

- Cemeteries in Dakhleh

- Amheida 2007–2009: New Results from the Excavations

- Les Nécropoles d’el-Deir (Oasis de Kharga)

- Yale University Nadura Temple Project: 2009 Season

- al-Qasr: the Roman Castrum of Dakhleh Oasis

- Five Roman-Period Tunics from Kellis

- A Remark on the Poll Tax Rate in Kysis

- Controlling the Borders of the Empire: the distribution of Late-Roman ‘forts’ in the Kharga Oasis

- Painted Surfaces on Mud Plaster and Three-Dimensional Mud Elements: The Status of Conservation Treatments and Recommendations for Continuing Research

- The Survey Project at el-Deir, Kharga Oasis: First Results, New Hypotheses

- Amheida: Architectural Conservation and Site Development, 2004–2009

- Vine and Acanthus: decorative themes in the wall-paintings of Kellis

- The Church Complex of ‘Ain el-Gedida, Dakhleh Oasis

- Christianity on Thoth’s Hill

- Coins as Tools for Dating the Foundation of the Large East Church at Kellis: problems and a possible solution

- The Church of Dayr Abu Matta and its Associated Structures: an overview of four seasons of excavation

- The Christian Necropolis of el-Deir in the North of Kharga Oasis

- Ceramics from ‘Ain el-Gedida, Dakhleh Oasis: preliminary results

- Coptic Ostraka from Qasr al-Dakhleh

- Naqlun: the Earliest Hermitages

- Contribution of Textiles as Archaeological Artefacts to the Study of the Christian Cemetery of el-Deir

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Oasis Papers 6 by Roger S. Bagnall, Paola Davoli, Colin A. Hope, Paola Davoli, Colin A. Hope in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Egyptian Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.