![]()

1

Introduction

‘In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.’ So the book of Genesis itself begins – a beginning about a beginning in which a Person (God) sets the cosmos in motion. This is where the story starts, by addressing three fundamental human questions: Was there a beginning? Are we living in a creation? Who created? The scale of this story, we understand immediately, will be grand; the questions that it seeks to answer will be huge. Why do we encounter the world as an ordered place in which life flourishes? Where do human beings fit into the scheme of things? How are they supposed to live, and what are they supposed to do? Why is there evil in the world, and why is there suffering? What is God doing in the cosmos to rescue it from evil and suffering? How do Abraham and his descendants fit into that plan? The storyteller – traditionally Moses – is nothing if not ambitious. So far as we can tell, those who preceded him were content to pass on smaller accounts of narrower matters – a story about Cain and Abel, for example (now related in Genesis 4), or a genealogy of the descendants of Adam down to Noah and his sons (now found in Genesis 5).1 Perhaps some stories had already been collected into larger cycles of stories about particular characters, like Jacob.2 These resources are now gathered up together, however, and woven into a coherent and sustained account of the universe and of ancient Israel’s place within it, which continues beyond the confines of Genesis into the remainder of the Pentateuch, and then into the subsequent narrative books of the Old Testament (OT) (Joshua to Kings). Ancient myths, genealogies, etiologies, and other stories – all are deployed in this astonishingly bold project.

The structure of Genesis

These various resources have been incorporated into the book of Genesis by means of a particular structuring device – a repeated pattern of words that marks off one section of Genesis from another, often referred to in modern biblical scholarship as the ‘toledot formulae’. In Hebrew, the words are ’elleh toledot, and these words have been translated into English in a number of ways, including ‘these are the generations of’, ‘this is the family history of’, and ‘this is the account of’. They always stand at the beginning of the section of the book to which they refer, and they are almost always followed by a personal name, as in Genesis 6.9, ‘This is the family history of Noah.’ The person named after the ‘formula’, however, is not necessarily the main character in the section of Genesis that follows it, which is often much more about his descendants. The account of Terah’s line, for example, hardly mentions Terah himself; it concerns, centrally, Abraham and his family (Genesis 11.27—25.11).

There are 11 toledot formulae in total, dividing Genesis into 11 sections (which I shall refer to as ‘acts’ in an unfolding drama), to which we must add a twelfth – since we must account for the material in Genesis 1.1—2.3 that precedes the first ‘formula’. We may outline the structure of the book in the following manner, therefore:

1.1—2.3 | (1) Prologue |

2.4—4.26 | (2) The ‘family history’ of the heavens and the earth: Adam, Eve, Cain and Abel, down to Seth and Enosh. This is the only exception to the rule about a personal name following ’elleh toledot. Here the cosmos itself is imagined as the progenitor of the human race, no doubt because Adam emerges from the ‘womb’ of the ground (Hb. ’adamah, Gen. 2.7). |

5.1—6.8 | (3) The family history of Adam down to Noah, prior to the great flood |

6.9—9.29 | (4) The family history of Noah, whose family survives the flood, down to Shem, Ham and Japheth (and Ham’s son Canaan) |

10.1—11.9 | (5) The family history of Shem, Ham and Japheth: the origins of the nations after the flood, including the account of the scattering at Babel |

11.10–26 | (6) The family history of Shem |

11.27—25.11 | (7) The family history of Terah: his son Abraham and his family |

25.12–18 | (8) The family history of Ishmael, Abraham’s ‘unchosen’ son |

25.19—35.29 | (9) The family history of Isaac, Abraham’s chosen son |

36.1–8 | (10) The family history of Esau, Isaac’s ‘unchosen’ son |

36.9—37.1 | (11) A second account of the family history of Esau |

37.2—50.26 | (12) The family history of Jacob, Isaac’s chosen son: the 12 brothers, especially Judah and Joseph |

It is important to note that the endpoints of each of the ‘acts’ marked off by toledot formulae represent important transitions in the story of Genesis:

4.26 | ‘At that time men began to call on the name of the LORD’ – the beginning of the worship of Yahweh, which prepares us for Noah |

6.8 | ‘Noah found favour in the eyes of the LORD’ – Noah is identified as a worshipper of Yahweh, which will be crucial in the story of the flood |

9.29 | ‘Altogether, Noah lived 950 years, and then he died’ – the end of the ‘old world’ and the point of transition into ‘the world and its peoples as we know them now’ in Genesis 10 (the descendants of Shem, Ham and Japheth) |

11.9 | ‘The LORD scattered them over the face of the whole earth’ – the context for the story of the line of Shem |

11.26 | ‘Terah . . . became the father of Abram’ – the transition into the Abraham story |

25.11 | ‘After Abraham’s death, God blessed his son Isaac’ – the transition from Abraham to his ‘unchosen’ son, Ishmael |

25.18 | ‘His [Ishmael’s] descendants settled in the area from Havilah to Shur’ – the transition back into the chosen line of Isaac |

35.29 | ‘[Isaac] breathed his last and died’ – the transition from Isaac into the story of his ‘unchosen’ son, Esau |

36.8 | ‘Esau (that is, Edom) settled in the hill country of Seir’ – the anticipated transition back to the chosen line of Jacob |

37.1 | ‘Jacob lived in the land where his father had stayed, the land of Canaan’ – the actual transition back to the chosen line of Jacob |

50.26 | ‘Joseph died at the age of a hundred and ten’ – the transition into the story of the exodus from Egypt |

The curiosity in this structure is the double account of Esau’s line. Because it disturbs the normal pattern in the book, most commentators have regarded the second account in Genesis 36.9—37.1 as having been inserted into the text after its basic shape had already been established. It is not easy to imagine why this addition might have been made, however. Was it perhaps to bring the total number of ‘acts’ in the book up to the number 12 – the traditional number of the Israelite tribes? Did it perhaps have something to do with the importance of Edom in biblical thought as a crucial player in the advent of messianic rule in the world?3 We can only guess.

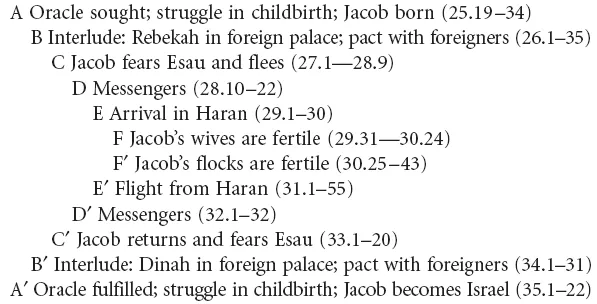

The toledot formulae, then, explicitly indicate the overall structure of the book of Genesis. Within the various acts in the drama, moreover, a plausible case can often be made for the presence of further structuring devices. For example, Bruce Waltke regards the Jacob cycle of stories in Genesis 25.19—35.22 (most of Act 9) as possessing what he calls a ‘concentric pattern’:

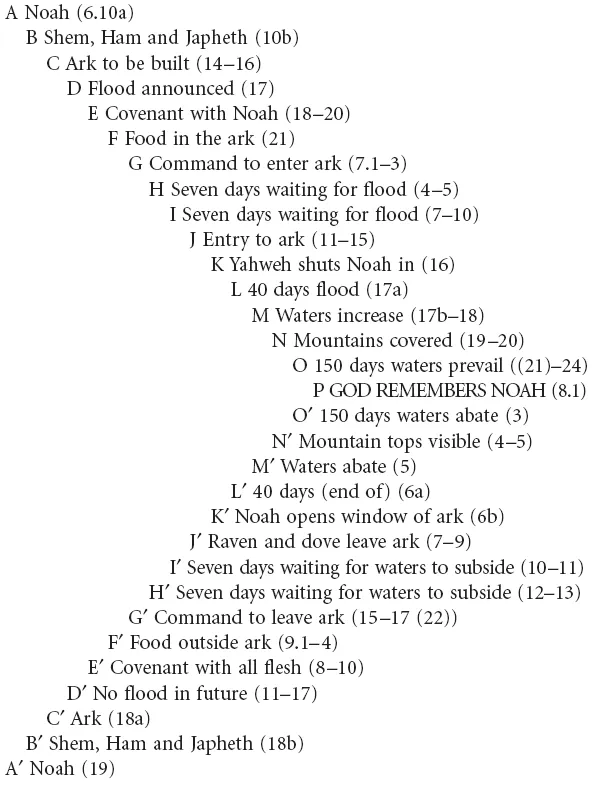

Waltke also regards the Abraham and Joseph cycles as having the same concentric pattern – like a ‘chiastic’ pattern, but possessing a double rather than a single centre (F and F′).4 Certainly chiasmus is a well-established literary reality in the OT, and others have argued for it persuasively in other parts of Genesis. Gordon Wenham has tried to show, for example, that the story of the great flood in Genesis 6.10—8.19 appears in chiastic form (he calls it a ‘palistrophe’), the waters rising until God remembers Noah in Genesis 8.1, after which they begin to recede.5 Wenham represents the matter thus:

In seeking such smaller structures within Genesis we are, of course, inevitably working at a more hypothetical level than in the case of the larger toledot-structure for the whole book. These hypotheses often appear to cast light, however, on otherwise opaque aspects of the text. In the case of the flood story, for example, the presence of a palistrophe helps to explain some redundancy in the text. For example, the period of ‘seven days’ waiting for embarkation in the ark is mentioned twice, in Genesis 7.4 and 7.10, even though it seems that only one period of time is in view. Why? Wenham suggests that this is a matter of literary necessity: the author requires in the first half of the palistrophe a parallel (H and I) to the two seven-day periods in the second, where the ark’s inhabitants are waiting for the floodwaters to subside (Gen. 8.10, 12; I′ and H′). In narrative reality we are dealing in the first case with one week, and in the second with two weeks, but the chosen structure forces the author to ‘duplicate’ the first time-period.

The story of Genesis

How does the story of Genesis unfold within this overall structure? Here I am simply going to outline the story, not describe it in any great detail. I shall be unpacking this outline in more depth in Chapters 5—11 below.

The book of Genesis begins, of course, with the story of the early history of the earth as a whole (Gen. 1—11) – often labelled by scholars as ‘the Primeval History’. The Prologue in Genesis 1.1—2.3 describes, first, the creation of the world. The earth and everything within it is characterized here as the good creation of a personal God, using the working week (six days, followed by a Sabbath) as its governing metaphor. Creation reaches its apex, first, in the creation of the land animals and human beings on the sixth day, and then in the resting of God on the seventh day. The human creatures are given an especially important role in creation as the ‘image-bearers’ of God: as well as multiplying in number like the other creatures, they are to ‘rule’ the earth and ‘subdue it’ (Gen. 1.28). This is the language of kingship; it denotes that God has delegated governance functions in the cosmos to men and women.

Act 2 of Genesis begins by exploring this human role in creation further. Now, however, the humans are not presented as kings, but as priests – set in God’s garden ‘to work it and take care of it’ (2.15). If in Genesis 1 humans appear ‘late’ on the scene, arriving to govern a kingdom that has already been created and is functioning well, in Genesis 2 they appear early, before any ‘shrub [has] yet appeared on the earth’ and before any ‘plant [has] yet sprung up’ (2.5); they are created in order to enable creation as a whole to function as God intended. Taking Genesis 1 and 2 together, it appears that human beings exist both as the apex and as the centre of cr...