![]()

PART ONE

THE PRESENTATION OF THE EVIDENCE

![]()

SECTION 2

INTRODUCTION

THE CHURCH AND ITS SETTING

The church of All Saints, Brixworth, is an historic building of outstanding importance both nationally and internationally. Built in a number of stages during the late 8th and early 9th centuries, it is one of a small number of churches in England surviving above ground from that relatively remote period and is one of the most complete; furthermore, it is still in use as a place of Christian worship. Its layout and general appearance are strikingly different from others in the region, which is rich in churches of the later Anglo-Saxon period; there are few comparanda nationally which are contemporary with the first period of construction at All Saints’, and the present interpretation of its subsequent rebuilding suggests that even the Period II church predates the general run of late Anglo-Saxon churches. Both its size and a later literary tradition indicate that it was originally of higher status (royal patronage is suggested) and greater significance than the simple parish church that it subsequently became: probably it was intended to be a ‘minster’ church served by a community of monks or priests. It bears comparison with foundations of the high aristocracy in Carolingian Europe. The historical importance of this ancient church has been recognised for at least 200 years and its unique features have often been explained away by the proposition that it is a Roman rather than an early medieval building. The complexities of its structure and the striking variety of its building materials have time and again challenged archaeologists and historians to investigate its origins and to understand more fully its physical development. The research reported here has led to a reassessment of the date of the original structure, now firmly placed in the late 8th century or very early in the 9th, and a recognition of the European context in which it was built. It is argued that the later remodelling of the church took place earlier than has been previously thought, perhaps before the end of the 9th century.

All Saints’ church was first described in detail by the antiquary and self-taught architect Thomas Rickman in the 1825 edition of his seminal Attempt to Discriminate the Styles of Architecture in England from the Conquest to the Reformation. Rickman did not apply the term ‘Anglo-Saxon’ to All Saints’, but by referring to changes to the fabric carried out from the Norman period onward claimed it by implication as pre-Conquest in date. (It may be noted in passing that the conquest of England in 1066 by the Normans of northern France is perceived in historical and art-historical thinking as a watershed; in the history of art and architecture it tends to be used as a somewhat inaccurate and contentious indication of the transition between the styles known elsewhere in Europe as pre-Romanesque and Romanesque.)

From the time of Rickman’s publication the church became the object of antiquarian attention, and large numbers of drawings and eventually photographs were produced, many of which are of importance for the study of All Saints’ today (see Section 4). Interest in the church and its history accelerated with the incumbency of the Reverend Charles Frederick Watkins (1832–73), who, within a decade of taking up office, had embarked on a series of observations and interventions, which culminated in an extensive restoration in 1865–66, aimed at returning the building to what he understood as its Anglo-Saxon form. He published an account of his investigations and interpretations in 1867 as The Basilica … and a Description and History of the basilican Church of Brixworth. His activities and conclusions are discussed in Section 4.

Since the time of Watkins the historical significance of the church has not been in doubt, though not all the interpretations of its fabric have been sustainable. Many learned persons have contributed to its study – famous names like J. T. Micklethwaite and Sir Henry Dryden are prominent – and it has figured largely in major works of architectural history by such eminent writers as Professor G. Baldwin Brown, Sir Alfred Clapham, Dr and Mrs H. M. Taylor and Professor Eric Fernie. Despite recent discoveries, from the excavated church at Cirencester to the Lichfield Angel, All Saints’ Brixworth retains its importance in the study of Anglo-Saxon architecture. Over eighty years ago it was characterised as ‘the most imposing architectural moemorial of the seventh century yet surviving north of the Alps’ (Clapham 1930, 33), and while it is now clear from both archaeological and architectural evidence, which was not available at the time, that the proposed date was incorrect, this much-quoted assessment of All Saints’ remains a measure of its historical and cultural significance.

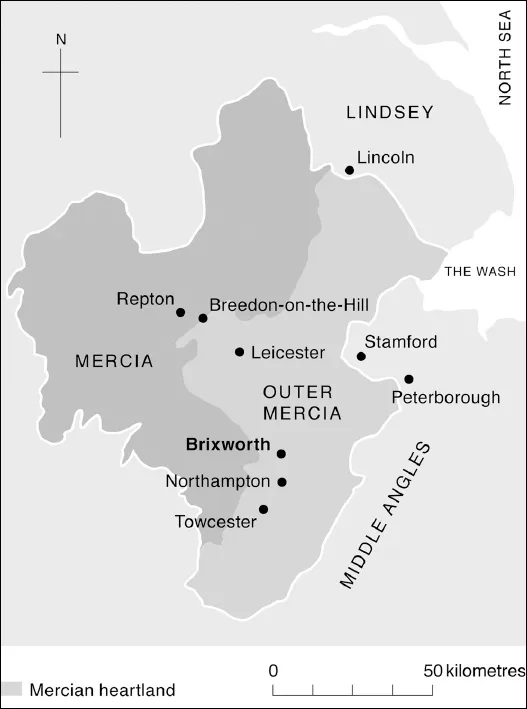

All Saints’ church now serves the parish of Brixworth, a settlement in the centre of the Midland county of Northamptonshire. Figure 2.1 shows its location in relation to the geography of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia and some of its principal sites. The positions of the parish within the traditional administrative divisions of Northamptonshire and of the church within the parish are shown in Figures 12.11 and 12.1 below. Brixworth village has been considerably expanded from its traditional core, especially to the south, where several residential estates have been built in the last half century. Its original centre lies at SP 748 709 and the present village occupies the western slope of a spur of high ground on the eastern side of a northern tributary of the River Nene, which is fed by a dendritic ‘fan’ of brooks. The brooks have cut down through Jurassic strata of the Northampton Sand Formation to the underlying Upper Lias Clay that forms the valley floor (see Section 6 for a full account of the local geology). The highest ground away from the valley is overlain with Boulder Clay (see Fig. 6.1). Medieval settlement generally preferred the ironstone exposures lying between the Lias heavy clays and Boulder Clay, and Brixworth conforms to this pattern, being sited on sandy ironstone, near the head of a small brook fed by water issuing at the base of the permeable strata. The site therefore has the benefit of a ready water supply lying adjacent to good agricultural soils.

Figure 2.1: Brixworth, Northamptonshire: location within Mercia, after Stafford, East Midlands in the Early Middle Ages (1985, fig. 36).

There are several sites of archaeological and historical interest in the parish, including an excavated Roman villa, three or four Anglo-Saxon cemeteries with cremations and furnished inhumations, and a recently excavated Anglo-Saxon settlement site (see Section 12, subsection The Archaeological Context).

THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE RESEARCH COMMITTEE AND ITS PROGRAMME

The First Decade

The fame of the church was not the sole reason for the foundation of the Brixworth Archaeological Research Committee (BARC) in 1972. The expansion of the village referred to above took place in the context of the designation of certain towns as overspill areas. In the immediate area two such New Towns were established, with their own Development Corporations, at Peterborough and Northampton. Only seven miles north of Northampton, Brixworth was a prime candidate for expansion. The eminent archaeologists who formed the core of the original Committee, and who are referred to in the Foreword and Preface, saw their task as safeguarding the history and archaeology of the whole parish, and in the early days considerable efforts were made to investigate sites designated for development. Many of these investigations proved negative. The Committee’s remit did not include the more general investigation of unthreatened sites, but one of its members, David Hall, with the aid of local fieldworkers, undertook privately a considerable programme of fieldwalking and topographical research, which led to the recognition of many potential occupation or settlement sites from the prehistoric to the medieval periods. Understanding of Anglo-Saxon Brixworth has been considerably furthered by his efforts, the significance of which for the study of the church is assessed in Section 12, subsection (a) The Archaeological Context.

Excavation

Some rescue archaeology was carried out in the early days, but all in the context of the church and its immediate environs. The site of a new vicarage was excavated in 1972 (Everson 1977), which identified the probable extent of the early burial ground, and a small excavation by Hall when mains water was being introduced into the church yielded valuable information about the structure to the immediate west of the nave (Hall 1977). By the second half of the 1970s, however, it appeared that monitoring the expansion of the village would not yield the expected archaeological dividends, and the Committee concentrated its efforts on the study of the church. Ironically, it was only after the abandonment of this early objective that fieldwalking by others on the site of the proposed A508 by-pass identified an Anglo-Saxon settlement site in the south of the parish. Threatenened by the construction of yet another housing estate, it was excavated in 1994, revealing a number of Anglo-Saxon timber buildings (Ford 1995). Meanwhile, however, BARC had set up a project to investigate the church, initially by non-destructive survey, as described in Section 5, including the then innovative recording of the petrology of the standing fabric (interim report by Sutherland & Parsons 1984, and see Sections 6 and 10 below). Water once again offered the opportunity for archaeological excavation when the church’s retained architect advised that a French drain along the north wall of the church was necessary to counteract penetrating and rising damp. The line of the proposed trench was investigated by the then Northamptonshire Archaeological Unit in 1981 and generous grant aid enabled the dig to be extended for research purposes into early 1982, with important results for the study of the church (Audouy et al. 1984, and see below, Section 8). The most obviously significant of these was the discovery of a ditch pre-dating the church, into which the foundations of the porticus to the north of the present tower had been dug. Eighth-century material from the fill of this ditch made it clear that the date of the surviving structure could not be as early as the previously assumed late 7th century, a date inferred from the scant historical evidence, the reliability of which is discussed in Section 12d. This has led to a fundamental rethinking of the chronology of the church building and its position in architectural history.

The Surveys and their Results

The Committee’s ongoing commitment was to survey, however. The establishment of an accurate ground plan was the first essential, and a new plan survey was carried out for BARC by the then church architect, Mr E. A. Roberts. This was subsequently refined by the excavation and survey teams and then replaced entirely by a more accurate EDM survey by the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England in the late 1980s, whose plan forms the basis for all the diagrams in this monograph.

The RCHME had already carried out a photogrammetric survey at the beginning of the Committee’s activities and the supplementing of that by hand-drawn surveys of the church’s elevations became the centre of the programme of work from 1976, when the first short season of drawing took place (described in detail in Section 5). Seasons of recording took place annually until the early 1990s, by which time the following had been drawn to scale: all the external elevations with the exception of the west and south walls of the southeast chapel (the former being newly built in the 19th century and the latter having been included in the photogrammetry); the interior faces of the arches of the nave arcades; and the interior elevations of ...