Fuel Cells

Dynamic Modeling and Control with Power Electronics Applications, Second Edition

- 411 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Fuel Cells

Dynamic Modeling and Control with Power Electronics Applications, Second Edition

About this book

This book describes advanced research results on Modeling and Control designs for Fuel Cells and their hybrid energy systems. Filled with simulation examples and test results, it provides detailed discussions on Fuel Cell Modeling, Analysis, and Nonlinear control. Beginning with an introduction to Fuel Cells and Fuel Cell Power Systems, as well as the fundamentals of Fuel Cell Systems and their components, it then presents the Linear and Nonlinear modeling of Fuel Cell Dynamics. Typical approaches of Linear and Nonlinear Modeling and Control Design methods for Fuel Cells are also discussed. The authors explore the Simulink implementation of Fuel Cells, including the modeling of PEM Fuel Cells and Control Designs. They cover the applications of Fuel cells in vehicles, utility power systems, and stand-alone systems, which integrate Fuel Cells, Wind Power, and Solar Power. Mathematical preliminaries on Linear and Nonlinear Control are provided in an appendix.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1 Introduction

1.1 Past, Present, and Future of Fuel Cells

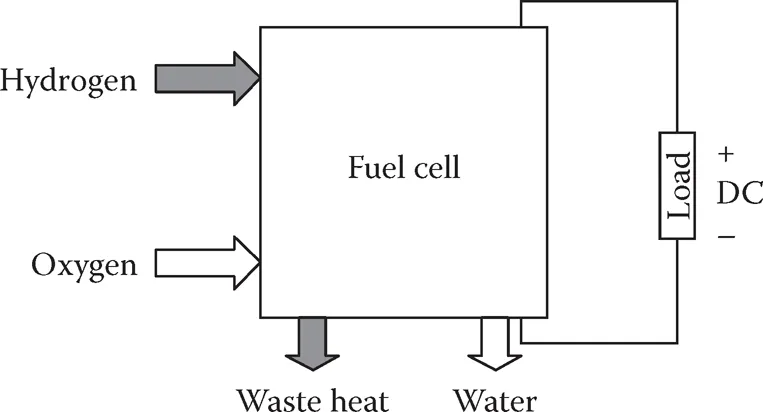

1.1.1 What Are Fuel Cells?

1.1.2 Types of Fuel Cells

1.2 Typical Fuel Cell Power System Organization

1.3 Importance of Fuel Cell Dynamics

1.4 Organization of This Book

References

- F.Barbir and T.Gomez, Efficiency and economics of PEM fuel cells, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 22(10/11), 1027–1037, 1997.

- A.M.Borbely and J.G.Kreider, Distributed Generation: The Power Paradigm for the New Millennium, New York, CRC Press, 2001.

- F.Barbir, PEM Fuel Cells: Theory and Practice, Elsevier Academic Press, Burlington, MA, USA, 2005.

2 Fundamentals of Fuel Cells

2.1 Introduction

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Authors

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Fundamentals of Fuel Cells

- 3 Linear and Nonlinear Models of Fuel Cell Dynamics

- 4 Linear and Nonlinear Control Design for Fuel Cells

- 5 Simulink Implementation of Fuel Cell Models and Controllers

- 6 Applications of Fuel Cells in Vehicles

- 7 Application of Fuel Cells in Utility Power Systems and Stand-Alone Systems

- 8 Control and Analysis of Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems

- 9 Optimization of PEMFCs

- 10 Power Electronics Applications for Fuel Cells

- 11 A PEM Fuel Cell Temperature Controller

- 12 Implementation of Digital Signal Processor-Based Power Electronics Control

- Appendix A: Linear Control

- Appendix B: Nonlinear Control

- Appendix C: Induction Machine Modeling and Vector Control for Fuel Cell Vehicle Applications

- Appendix D: Coordinate Transformation

- Appendix E: Space Vector PWM

- Index