![]()

HISTORICIZING CHILDHOOD

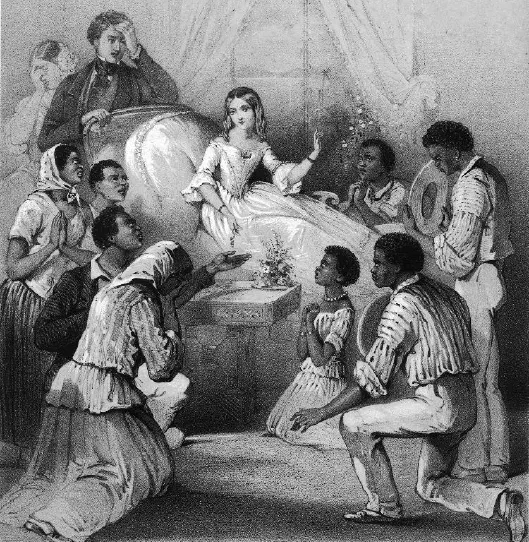

Susannah Bricks, one of the children featured in James Janeway’s A Token for Children (1671), cries out, “Behold, I was shapen in iniquity, and in sin did my mother conceive me, and I was altogether born in sin!” (59). Fortunately, she repents of her sin before dying at the age of fourteen from the plague. Such naturally sinful children also appear throughout nineteenth-century stories about boys at boarding schools, as in Thomas Hughes’s Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1857), in which the natural wickedness of boys must be constantly policed, managed, and eventually overcome by the good example of their masters and the disciplinary policies of the school. In contrast, the child speaker of William Blake’s poem “The Lamb” (1789) sees himself, the lamb, and the baby Jesus as sharing a natural innocence, which the character of Little Eva in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) also embodies. Her father, St. Clare, the owner of a large slaveholding plantation in the American South, wonders when he sees his virtuous daughter enjoying the company of the slave Tom, “What would the poor and lowly do, without children?” (185). St. Clare sees children like Eva as embodying innocence, not sin: “Your little child is your only true democrat… . This is one of the roses of Eden that the Lord has dropped down expressly for the poor and lowly, who get few enough of any other kind” (185).

The history of children’s literature cannot be understood fully without considering the history of childhood, and children’s literature seems inextricably bound to issues of audience. What kinds of writing are appropriate or inappropriate for children? What is useful for the instruction or education of children? What will children find interesting or enjoyable? What are children of different ages prepared to read or understand? How we answer these questions—which might be asked by adults who write, publish, purchase, recommend, or teach children’s literature—depends on how and what we think about children. Are children born into savagery or sin, inclined to delinquency in the absence of proper guidance, and in need of strict discipline? The children in the works just cited represent different models of childhood and ideas about children. While adults read and enjoy children’s literature as well, understanding the history of childhood helps us to understand the readers who are presumably the primary audience for children’s literature.

As historians of childhood have discovered, the nature of that audience is anything but a simple matter. Since the groundbreaking publication of Philippe Ariès’s Centuries of Childhood in 1960 (trans. in 1962), researchers have made it clear that how childhood has been defined—indeed, who counts as a child—has often differed at different times and in different places, sometimes radically. Complicating the study of the history of childhood is the fact that at any given moment multiple and even contradictory ideas about children and childhood coexist; what we think about children and childhood and the ways real children actually live do not always correspond. In addition, age intersects with other key dimensions of social experience, such as sex/gender, class, race, nation, region, religion, and ethnicity, so that the lives of children often vary widely even at the same historical moment. Considering all these factors produces a very complex picture of what it means to be a child. What, then, do we mean when we speak of children or childhood? Rather than providing a historical chronology, we answer this question in the section that follows by focusing on models of childhood most prevalent in British and US cultural history since the seventeenth century, and we approach this history in terms of models of childhood in order to distinguish clearly between ideas about “the child” and the experiences of living children.

HISTORICAL MODELS OF CHILDHOOD

In the modern age, a number of competing models or conceptualizations of children and childhood circulate that affect how children are treated and perceived and how children live and perceive themselves. The history of childhood has not unfolded in a linear way, and newer understandings have not simply replaced earlier ones. Rather, different models of childhood, more or less dominant at different moments and in different places, overlap and intermingle to produce a complex and sometimes contradictory picture of what it means to be a child. We describe some of the most commonly encountered models of childhood separately, but these models rarely operate in isolation. Even seemingly outdated models continue to overlap with others and influence how we think and write about children. Rather than simply being a framework for classifying child characters, these models provide a way to think about the assumptions underlying how children are represented in children’s literature so that those representations can be analyzed critically.

The Romantic Child

One such model is that of the child as the embodiment of innocence, or the Romantic child, such as Little Eva in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. John Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) sets forth the tabula rasa theory, the notion that the mind of a child is a blank slate: “Let us then suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper, void of all characters, without any ideas; how comes it to be furnished? Whence comes it by that vast store, which the busy and boundless fancy of man has painted on it with an almost endless variety? To this, I answer in one word, From experience [sic]” (59). Later Locke would write in Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693) that “the difference to be found in the manners and abilities of men is owing more to their education than to anything else [and thus] we have reason to conclude that great care is to be had of the forming of children’s minds” (25). Locke’s theory of human nature held practical consequences for the rearing of children, especially in matters of education and discipline. Locke thought that children should be left “free and unrestrained” as much as possible in order to explore the world around them and that they possess a “natural gaiety,” which could be spoiled by too much adult interference (39). Similar sentiments were expressed by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in Emile (1762), his treatise on education. In Book II, Rousseau exhorts parents to abandon restrictive educational and disciplinary practices that make the lives of children unbearable drudgery:

Love childhood; promote its games, its pleasures, its amiable instinct. Who among you has not sometimes regretted that age when a laugh is always on the lips and the soul is always at peace? Why do you want to deprive these little innocents of the enjoyment of a time so short which escapes them and of a good so precious which they do not know how to abuse? Why do you want to fill with bitterness and pains these first years which go by so rapidly and can return no more for them than they can for you? (79)

The child as conceived in Emile has natural innocence and virtue that must simply be molded by the sensitive guidance of an adult tutor, but Rousseau warns against forcing adult reason onto the child, who is not ready for it. “To know good and bad, to sense the reason for man’s duties,” he writes, “is not a child’s affair. Nature wants children to be children before being men. If we want to pervert this order, we shall produce precocious fruits which will be immature and insipid and will not be long in rotting” (90). In statements such as these, Rousseau works to emphasize the link between childhood and nature.

In Harriet Beecher Stowe’s controversial novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), Eva is constructed as possessing a racialized childhood innocence denied to African American children.

By the end of the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth, Romantic poets such as Blake in Songs of Innocence (1789) and William Wordsworth in “Tintern Abbey” (1798) further solidified the association of childhood with innocence and purity. Influenced by thinkers such as Locke and Rousseau, they found in children and childhood a contrast to the apparent corruptions of body and soul bred by industrialization. Wordsworth’s 1807 publication of “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” reflects this Romantic idealization of childhood:

Heaven lies about us in our infancy!

Shades of the prison-house begin to close

Upon the growing Boy,

But He beholds the light, and whence it flows,

He sees it in his joy;

The Youth, who daily farther from the east

Must travel, still is Nature’s Priest,

And by the vision splendid

Is on his way attended;

At length the Man perceives it die away,

And fade into the light of common day. (lines 66–76)

This conception of children as somehow purer and more virtuous than adults, closer to nature and God, and beautified by their naïveté persists in contemporary times, both in literary and filmic representations of children and in public policy debates involving the “protection” of children and childhood ignorance. Consider the refrain to “stay gold” in S.E. Hinton’s landmark young adult novel The Outsiders (1967), in which teenager Johnny encourages his friend Ponyboy to retain his “childlike” wonder, or the public hysteria surrounding Surgeon General Joycelyn Elders’s suggestion in 1994 that masturbation might be an acceptable means of avoiding HIV transmission among young people, an idea that clearly conflicted with the conception of childhood innocence and led to Elders’s forced resignation. What we like to think about children has practical consequences.

This Romantic conception of childhood can emphasize different qualities and sometimes appears inconsistent. To some Romantics, the minds of children are blank slates, and children must be molded by adults and imprinted with culture. Others influenced by the Romantic tradition see children as naturally happy, carefree, innocent, or pure and thus likely to be disappointed, deformed, or corrupted by experience and maturation. Some Romantic thinkers regard children as savage and uncivilized in their proximity to nature and beasts, in contrast to more cultured and disciplined adults. Others emphasize their natural insights or abilities, which adults lack or have lost. What these various understandings share is the sense of children as almost superior to adults in some ways and as aligned with nature, beauty, or spirituality.

Many classics of children’s literature reflect a Romantic vision of childhood. In Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden (1911), the author depicts the three child protagonists as having an affinity with nature: the sickly, upper-class Mary and Colin both find health and vigor by working in the garden, and the kindly, working-class Dickon communes with animals and maintains his hardy constitution by always being outside. The eponymous protagonist of Virginia Hamilton’s M.C. Higgins, the Great (1974), the first novel by an African American author to win the prestigious Newbery Medal, lives on a mountain and fears the dangers posed to his home and family by the after-effects of strip-mining. The novel’s depiction of M.C. as crucial to his family’s salvation and as the one most conscious of the dangers of technology links him to the Romantic tradition of seeing children as embodying an earlier, purer, agrarian past amid urbanization and industrialization.

The Sinful Child

Another conceptualization competes with the notion of children as the embodiment of innocence: that of the child as sinful and in need of discipline and training. Puritan theology and social customs have left us with the image of the sinful child born corrupted by the original sin of the biblical Adam and Eve, easily swayed to do wrong, and susceptible to evil. Historian Steven Mintz has examined the diary kept by New England Puritan Samuel Sewall between 1673 and 1729. As Mintz explains,

Sewall’s diary reveals a society that believed that even newborns were innately sinful and that parents’ primary task was to suppress their children’s natural depravity. Seventeenth-century Puritans cared deeply for their children and invested an enormous amount of time and energy in them, but they were also intent on repressing what they perceived as manifestations of original sin through harsh physical and psychological measures. Aside from an occasional whipping, Sewall’s primary technique for disciplining his children was to provoke their fear of death, sin, and the torments inflicted in hell. (2)

By the mid eighteenth century, Evangelicals in Britain and the United States had reshaped religious understandings of children. Less severe than their Puritan predecessors, they permitted play and sought to restrict child labor. While the sense of children as born sinful and damned became less pronounced in Evangelical discourse, the need to save, discipline, and educate them remained central. The Sunday School movement emerged in Britain between the 1750s and 1780s in order to address these needs, with Evangelicals such as English-born Robert Raikes establishing Sunday schools to introduce children to Christian thought and provide alternatives to mischief or criminal behavior, especially for poor and working-class children.

Jessica’s First Prayer (1867), written by English Methodist Hesba Stretton (penname of Sarah Smith), indicates the Evangelical view of the child in need of both spiritual and economic care. Jess, the protagonist, is dirty, hungry, and miserable, neglected and abused by her drunken mother. When Mr. Daniel Standring, who keeps a coffee stand in London, attempts to catch Jess at stealing by deliberately dropping a penny in front of her, she resists the temptation and returns it to him. She later follows him into a church and learns about God and faith from the minister and his children. Though she needs spiritual salvation and social training, she is not exactly the evil or sinful child described by Puritan writers even if the text implies that her poverty and lack of spiritual education would eventually lead her to depravity, as her mother had been led. Evangelicals, influenced by both religious doctrines and the increasingly popular views of the Romantics, imagined the child as a composite of the sinful and Romantic child.

Today, manifestations of this notion of childhood sin might take more secular forms, couched in the pseudopsychological language of impulse control and developmental immaturity or in the pseudoanthropological language of savagery or untamed wildness, but they still arise in references to the schoolyard cruelty of children or to the need for teenage curfews as a way to reduce crime. The sinful or depraved child frequently appears onscreen or in written fiction as well, as in William March’s 1954 bestseller, The Bad Seed, which features an adorable suburban girl in pigtails who turns into a chillingly cold-blooded murderer. The Bad Seed was later made into a hit Broadway play and a critically acclaimed film. George R.R. Martin’s fantasy novel A Game of Thrones (1996) was also a bestseller that was later adapted into a successful television series, and it too features a malevolent boy, Prince Joffrey, who later becomes a tyrannical child king. Clearly, the figure of the evil child still resonates. This image is remarkable for the way it contrasts so strikingly with the image of the child as the embodiment of innocence.

While the model of the sinful or evil child still persists most obviously in works of horror, it can also be seen throughout children’s literature even if the child’s evil is not attributed to original sin. The character Draco Malfoy in the Harry Potter series belongs to the tradition of the evil child, even though his evil is influenced by his upbringing and his family’s service to Voldemort. Another evil child, Paul, in Edward Bloor’s Tangerine (1997) blinds his younger brother, commands a friend to murder another youth, and steals from his neighbors, and yet the novel provides little explanation for Paul’s horrific actions. Though representations of the Romantic or sacred child now appear more frequently and serve as the dominant conceptions of children, the evil or sinful child continues t...