Overview

Our ability to learn and store what we have learned is a remarkably important capability, pervasive to nearly every aspect of our lives. Consider the following “thought experiment”: imagine you had the opportunity to have the vacation of your dreams but would never remember it, or you could have the memory of the vacation but would not have taken the trip at all. Which would you select? Most of us are initially pulled in the direction of wanting the trip but having no memory of it—but, of course, you can see the problem. Having no memory of the trip means the trip will have no influence on us afterwards. No happy memories, no feeling of satisfaction, no photos or videos to share. In fact, we’d probably still be pining to take that trip—the very one we had already had—because we would’ve forgotten we’d already taken it! It may be counter-intuitive now, but having a memory of the trip, even if a false one, could likely have a larger impact on us than a forgotten journey.

“Buddy O’Dell”

As a young man, my grandfather Delor “Bud” Benoit was a professional boxer who went by the show name “Buddy O’Dell,” although he was not Irish (see Fig. 1.1). He credited the violin lessons he was made to take as a child for his early boxing experience—he had to fight off bullies as he was walking to and from lessons while protecting his violin. He fought Jake La Motta in 1942 and lost in a close decision. His boxing experience left him with occasional vision problems, but he was otherwise in very good health. While serving as Seaman Specialist in the US Navy in World War II, his ship, the USS Princeton, was hit by a 500-pound bomb from a Japanese dive bomber. Despite his dislocated shoulder from the blast, he was able to tie a lifeline around a wounded crewmate and lower his body down a stairwell before a lieutenant encouraged Bud to jump off the deck into the ocean. The Princeton continued to burn and secondary explosions began, taking more lives, until rescuing destroyers had to sink it.

Bud was a serious poker player, and (as the family legend goes) he would sometimes travel to Las Vegas and gamble until he had enough money to pay the rent. He was always a smooth, easygoing talker who seemed to be able to hold a conversation with anyone; maybe it was the result of his blue-collar upbringing plus his university experience at Michigan State University on a boxing scholarship. He eventually earned a JD, and spent his career doing administrative work for State Farm Insurance.

Figure 1.1 Bud’s boxing days

Today he is 91 years old and living in a monitored group home for seniors. His health has always been exceptionally good, but gradual changes to his memory had started to occur. The loss of his memory meant not keeping up with basic home cleanliness. He kept firing the cleaning service his adult daughter (my mother) would hire for him, telling them he could take care of it himself. His dogs would eliminate about anywhere, and he would not remember to clean up after them. His stove had to be replaced after the family found a nest of rats living in the back of it. He came to believe he didn’t have enough money to get by, even though he was fairly well off. But he didn’t remember. Eventually, scam artists and occasionally his bank would take advantage of his inability to remember his money situation. At one point, family members had to camp outside his house to scare off a woman coming to collect a large sum of money he had promised her as down payment for some future return investment (similar to that Nigerian prince email scam, except that criminals were physically at your home!).

The decision to move Bud from his long-term home was not an easy one for my mother. Even though he adapted to his new surroundings fairly well, he repeatedly asked to return to his old home, since that’s what he remembered as his. He once talked a hospital shuttle driver into taking him there instead of his group home. It had been emptied months earlier, and he had no key to get in. By now, despite his acumen for talking people into doing what he wanted, he no longer remembered or recognized family members, including my mother. It’s been this way for some time. The loss of memory begins to take away who one was, after a while, and adjusting to new circumstances is difficult.

Recently, my mother arrived at the group home, and Bud met her at the door. He knew her name, and asked her to come in and sit. Once seated, he turned to her and said, “All right. What am I doing here?” In the conversation that followed, my mother and her father had a very lucid conversation about what had been happening to him over the past few years and the decisions that had been made to that point. She explained. He apologized for the trouble he had caused.

It was not to last. By the next visit, he was back to not remembering. He has adjusted to his new home and seems happy, but he remembers little. It is as if, somewhere under the memory loss and likely brain decay, the person I know as my grandfather is still there, unable to get out (see Fig. 1.2).

Figure 1.2 A recent photo of Bud

This has become a common story. Many families, particularly those with long-living parents, are running into events like these. While the physical form of the person is still present, and often their habits and even personality remain intact, the loss of memory is catastrophic for individual functioning. The “remembering power” of the brain is so beneficial that its loss is extremely noticeable.

In this book, we will explore what it means to learn and to know. We will explore the vast amount of research on learning and the kinds of memory, the amazing diversity of activities that memory supports, and what happens when memory fails us. My goal is to convince you that, ultimately, we are what we learn and remember. Much of who we are and who we believe ourselves to be is determined not by what precisely has happened to us, but by what we remember of what has happened to us and the stories we believe those remembrances tell. To start our in-depth study of memory, let’s examine where the field of study on learning and memory has been and where it is today. We’ll start with classic philosophical approaches and then move to more recent, contemporary approaches.

Early Philosophical Approaches

It’s understandable to question whether it is worth looking back to earlier centuries to understand what we do today. It doesn’t always feel relevant, and instead is like rehashing the past. In this situation though, questions about learning, memory, and the nature of knowledge reach back a long ways. Prior to psychological science, the nature of mind and memory were exclusively in the domain of philosophy and theology. In many cases, the general ideas that philosophers had about learning and memory are still represented in modern theories. So, while delving so far into the past can seem like a detour, what you will find in this section are ideas and relationships that are prescientific, but are around to this day. Having a basic understanding of these ideas will prepare you for the modern research and theory we’ll encounter in the next chapters.

Socrates’s Early Functionalism

The Greek philosopher Socrates (469–388 BCE) noted that many objects could be grouped together as “instances” of the same idea even if they do not look alike, such as different chairs. The physical, surface features were not always what mattered. He suggested that objects in our memory are based on their functions. That is, objects in memory are stored by the potential function that they may serve. For example, the diversity in what people consider to be “cars” is rather large, but it doesn’t seem to take us long to add new models we encounter into a “car” category. Socrates’s idea about this conceptualization of how memory for objects works allows that what we remember and know about the world isn’t constrained by the physical or material aspects of the real-world objects. Thus, whether a coffee mug is made of ceramic or plastic or steel is irrelevant to our being able to remember what a coffee mug is and to recognize one. Using Socrates’s conceptualization of knowledge, one can also recognize a coffee mug as a mug even if it is cracked or chipped. This “functional” approach to explaining how we know what objects are is an approach that is still around today.

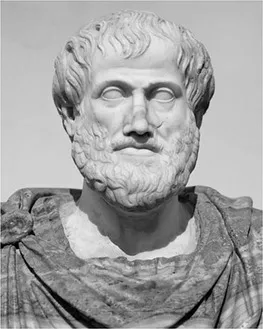

Aristotle’s Associationism

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (364–323 BCE; see Fig. 1.3) intuited a number of the issues and approaches that were later developed by other philosophers and psychologists. He based at least some of his intuitions on the theories of his teacher, Plato (427–347 BCE), who had used various metaphors to try to capture the nature of human memory. Plato had described memory as being like wax, on which impressions could be made. He noted that some people were better at recording memories than others. For some people, it was as if their wax was less pliable. This is an observation that psychologists now often call a matter of “individual differences.”

Likewise, Aristotle noted that memory is not particularly static or frozen, but could move; it has a relatively fluid nature. Thinking of one thing can cause one to think of or remember something else. Aristotle proposed that this fluid process of thinking and remembering obeyed a set of rules such as similarity, contiguity, and causal properties. For instance, remembering one event can remind us...