eBook - ePub

Turkey in the Global Economy

Neoliberalism, Global Shift and the Making of a Rising Power

Bülent Gökay

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Turkey in the Global Economy

Neoliberalism, Global Shift and the Making of a Rising Power

Bülent Gökay

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Since the late-1990s Turkey has emerged as a significant economic power. Never colonized and straddling the continents of Europe and Asia, it plays a strategically important role in a region of increasing instability.

Bülent Gökay examines Turkey's remarkable domestic political and economic transformation over the past two decades within the context of broader regional and global changes. By situating the story of Turkey's economic growth within an analysis of the structural changes and shifts in the world economy, the book provides new insights into the functioning of Turkey's political economy and the successes and failures of its ruling party's economic management.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Turkey in the Global Economy an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Turkey in the Global Economy by Bülent Gökay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politik & Internationale Beziehungen & Nahostpolitik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Nahostpolitik1.

An emerging market economy

“[O]ld geographies of production, distribution and consumption are continuously being disrupted and that new geographies are continuously being created. In that sense, the global economic map is always in a state of ‘becoming’; it is never finished. But the new does not simply obliterate the old. On the contrary, there are complex processes of path dependency at work. What already exists constitutes the preconditions on which the new develops.” – Peter Dicken (2007: 32)

“We have had a couple of hundred bad years, but now we’re back.” – Clyde Prestowitz quotes a Chinese friend1

The global political economy

During the period when the Turkish economy was being fully integrated into the world economy, the global system was experiencing one of its historic structural transformations when deep-seated movements and shifts of positions were affecting every single economy in the world. This is what soon came to be known as the global shift: a shift in the hegemonic structures of the world economy – a shift away from North America and Western Europe to the emerging economies of the Global South in Asia, Africa and South America. Drawing on comparative analyses, historians and political economists identify patterns and causes of hegemonic power decline, such as decreasing economic and technological resources relative to those of rising powers (Kennedy 1987; Grygiel 2006; Kupchan 2011). These studies inform contemporary theoretical debates on power transition from the powers in the Global North to the powers in the Global South, mainly based on the analyses of the economic rise of China, the growing assertiveness of Russia or the dynamism of India.

The definition of the global shift used in this book is based on Andre Gunder Frank’s 1998 thesis in Re-ORIENT: Global Political Economy in the Asian Age, which offers broad analytical tools that have proven their value in anticipating what is now increasingly acknowledged as a primary shift in the global system towards China and India as dominant emerging powers in the world.

I shall first consider whether, and if so how and with what consequences, the global system in this period has been going through a major shift. I shall then look at the role and position of Turkey, as a medium-sized emerging economy, within this period of global shift.

More than 50 years ago, Organski (1968) warned the United States and its Western allies that China would become the most serious threat to the US’s supremacy. Organski further suggested that an alternative power hierarchy, which may include other medium-sized regional powers, would emerge to challenge the declining dominant power of the US and its allies in the world system.2 Predicting the remarkable rise of China, Organski explained the dynamics of the potential power transition from the United States as a declining hegemon to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as a rising challenger in the international system. He predicted that the rise of China through its internal development would be enormous, that the power of China ought to eventually become greater and that the Western powers would find that the most serious threat to their supremacy would come from China (Organski 1968: 361–71).3

Later, in 1987, at the conclusion of his widely popular study of the global system titled The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, Paul Kennedy was probably the first observer to measure the actual beginnings of this global shift: “The task facing American statesmen over the next decades . . . is to recognize that broad trends are under way, and that there is a need to ‘manage’ affairs so that the relative erosion of the United States’ position takes place slowly and smoothly” (Kennedy 1987: 534). In chronicling the decline of the US as a global power, Kennedy compared measures of US economic health, such as its levels of industrialization and the growth of real GDP, against those of Europe, Russia and Japan. What he found was a power shift in the global system over the past 50 years that had been generated by underlying structural changes in the organization of its financial and trading systems. Many other authors have analysed the changing balance of global power architecture in a similar way (Mearsheimer 1990).

Later still, one year after the 2008 global financial crisis, Kennedy described the current level of the global shift as follows:

If one believes in the economists’ theory of “convergence” – that is, the coming closer together of the product and income of companies, regions and countries – then the conclusion is clear: as China, India, South Korea, Brazil, Mexico and Indonesia all “catch up,” the American share of things will relatively shrink. Sooner or later – and this debate really is about “sooner” or “later,” not about “if” – we are going to witness a major shift in the global balances of power. (Kennedy 2009)

The rise and decline of powers has always occupied a significant part of the more historically minded considerations of international relations. According to the calculations of Danny Quah, the centre of economic gravity in the world economy shifted from a point in the Atlantic (between North America and Western Europe) in 1980 to a location in the south-eastern corner of the Mediterranean in 2008, a location just south of Izmir, Turkey. In 1 CE, China and India were the world’s largest economies. First, European industrialization and later the rise of America drew the world economy’s centre of gravity into the Atlantic. As China has regained economic leadership, the centre is now retracing its footsteps towards the East. Extrapolating growth in the 700 locations studied, Quah calculated that by mid-century, “the global economy’s centre of gravity will continue to shift east to lie between India and China”. By economic centre of gravity, Quah is referring to the average location of the planet’s economic activity measured by the GDP generated across nearly 700 identifiable locations on the earth’s surface (Quah 2011: 7).

Throughout the modern history of international relations, there has been a recognizable pattern of the emergence of great power that is determined by structural material factors. The essential factor here is how economic growth creates uneven development, which is explained by David Landes: “Economic growth was now also economic struggle – struggle that served to separate the strong from the weak, to discourage some and toughen others, to favour the new . . . nations at the expense of the old. Optimism about the future of indefinite progress gave way to uncertainty and a sense of agony” (Landes 1969: 240).

In this historical process of great power shifts, some states achieve power but others lose it. This “differential growth in the power of various states in the system causes a fundamental redistribution of power in the system”, writes Robert Gilpin (1981: 13). This analysis is directly related to the definition of global hegemony. The concept of hegemony here refers to global leadership by one power, be it a state or a “historical bloc” of particular powers, whereby the reproduction of dominance involves the enrolment of other, weaker, less powerful entities and is constituted by varying degrees of consensus, persuasion and, consequently, political legitimacy. Force is not completely absent within such hegemonic arrangements but it tends to be the exception rather than the rule with regard to the upholding of the hegemonic order.

Global hegemony is a self-limiting, self-defeating and temporary condition in international affairs. That is because hegemonic power has the responsibility of organizing the international system, supplying public goods and intervening when necessary, and these all increase the pressures on and cost for the hegemon. There always comes a point when the hegemon finds itself over-committed and unable to bear the cost of maintaining the system any further. The hegemon prioritizes domestic obligations over its international commitments or finds it more difficult to stick to its global responsibilities. Either way, hegemony declines and collapses on itself and emerging chaos reigns until another hegemonic state, or a group of states, rises up and restores order. When the hegemony of a major power or global superpower is at the declining phase, this affects the entire world order and leads to instability. This not only affects the field of economic power; such economic power shifts will “have a decisive impact on the military/territorial order” (Kennedy 1987: xxii).

When a hegemonic power imposes its political and economic authority over a region, it does so in relation to its allies and its local protégés. Gramsci used the term “hegemony” in a very specific sense to signify that the dominant power leads the system in a direction that not only serves the dominant group’s interests but is also perceived by subordinate groups as serving a more general interest (Gramsci 1971: 106–20, 171). David Harvey’s use of the term is similar: “the particular mix of coercion and consent embedded in the exercise of political power” (Harvey 2005: 36). Peter Gowan’s theorization of American hegemonic leadership in the post-1945 era is probably the most detailed and coherent analysis. The US hegemony in the global system after 1945 depended on a system of regional alliances that gave the US the ability to directly influence and command the political strategies and security policies of the other main capitalist centres. This in turn led to the formation of an American protectorate system that covered the capitalist core, with a distinctive “hub-and-spokes” character that dictated that each protectorate’s primary military–political relationship had to be with the United States (Gowan 2003).

According to many experts, the US is facing a decline that has been more noticeable since the end of the Cold War. Although the US still clearly represents the largest and strongest economic and military power in the world, it is nevertheless struggling with severe weaknesses resulting from low economic growth and the protracted decline of the processing industry, predominantly in the field of innovative technological products. The US’s loss of momentum has been going on for decades and has led to a decline in its driving economic strength. A decline in productive capacity and the ever-widening gap between productive accumulation and financial accumulation has led to recurring financial and economic crises in every corner of the Western world (Dicken 2007: 41–62; Arrighi 2007: 149–72).

In parallel to this decline in the overall weight and influence of the US in world economics and politics, the past three decades has witnessed the emergence of other economic powers that have pushed themselves to the top position, and as a result, the global power balance has been altered significantly, with a fundamental shift towards a kind of multipolar world system. New centres with global influence have emerged in South East Asia, in particular China and India. South East Asia has maintained speedy growth and technological advancement because intra-regional trade, investment, GDP and per capita income have continued to increase in times of general sluggishness in the global economy. Other medium-sized states, some of which are regional powers, have also increased their power and influence in the same period, such as Mexico, Turkey, South Korea and Indonesia, all of which as a group came to be called emerging powers. China, countries in Latin America and Turkey opened up their economies around the same time in the 1980s, followed by India and Eastern Europe a decade later.

Figure 1.1 GDP growth (%) G20 countries, 2017 and 2018

Source: OECD (2017).

Within this group, China, India and Russia, and to some extent Brazil, can be considered potential great powers, or power poles, whereas the other emerging economies can be seen as regional powers or second-ranking global powers.

The massive economic achievement of China, India and certain other emerging economies has led to a debate about rising powers and a subsequent power shift at the top of the international order. All available economic data highlight that today we live in a world of power transition, with the world’s economic landscape rapidly changing and a very different world emerging. Although the US is still the world’s leading economic power, its supremacy has been significantly reduced as other competitors, in particular China and India, have emerged. Writing in 2007, Peter Dicken,

In these first years of the new millennium, the global economic map is vastly more complicated than that of only a few decades ago. Although there are clear elements of continuity, dramatic changes have occurred . . . there has been a substantial reconfiguration of the global economic map . . . Without doubt, then, the most important single global shift of recent times has been the emergence of East Asia – including the truly potential giant, China – as a dynamic growth region. (Dicken 2007: 68)

Major shifts of hegemony between states occur infrequently and are rarely peaceful. The transfer of power from the West to the East has been gathering pace since the late 1990s, and Washington think tanks have been publishing thick white papers charting Asia’s (China’s in particular) rapid progress in microelectronics, nanotech and aerospace and printing gloomy scenarios about what this means for America’s global leadership. The American administration considers China to be a potential “strategic competitor” and has exerted enormous pressure on it since the early 1990s (US National Security Strategy 2015).

China’s integration into the global economy began in the 1980s with its policy for special economic zones, which created four export processing zones offering tax exemption, cheap labour and land to multinational companies.4 As a result, capital flowed into China from all over the world and these economic zones acted as export platforms; provincial and local governments of China invested in such joint ventures with foreign investors. For more than three decades, China has marched to the banner of “reform and opening to the outside world” (China Daily 2007). Deng Xiaoping’s economic programme was regarded by many observers as a historical turning point of the twentieth century. At this stage, the policy of a US-dominated global system was one of “engagement”. With increased level of globalization and the entry of China to the World Trade Organization, engagement was intensified with the World Bank calling for privatization of state industry and the introduction of market prices in China. How ironic is it that now, three decades later, the USA increasingly regards a fast-expanding market economy in China as a serious threat to US global hegemony!

For more than a century, the US has been the world’s biggest economy, accounting for over 24 per cent of the world’s GDP in 2016, according to figures from the World Bank. The continuing uncertainty of the US economy and the decline of US technological leadership indicate that the time has come for the US to rethink its strategic economic options. Both the IMF and the World Bank now rate China as the world’s largest economy based on purchasing power parity (PPP), a measure that adjusts countries’ GDPs according to differences in prices (World Bank 2020b). James Kynge writes, “Chinese companies are widely recognized as world leaders, or as being at the cutting edge, in 5G telecoms equipment, high-speed rail, high-voltage transmission lines, renewables, new energy vehicles, digital payments, areas of artificial intelligence and other fields” (Kynge 2020).

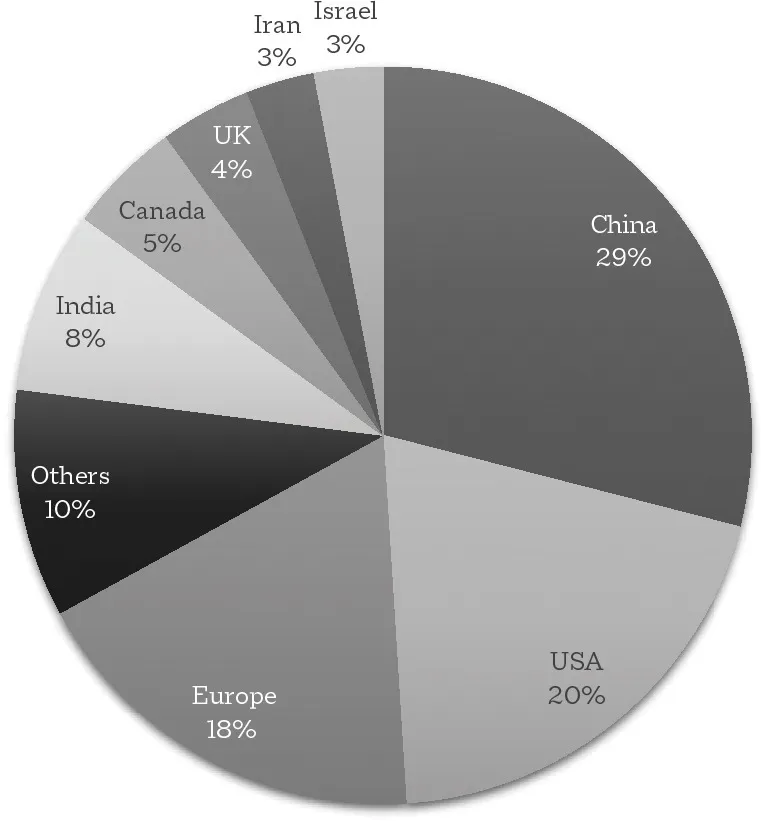

Macro Polo’s Global AI Talent Tracker identifies China as the country of origin for 29 per cent of the world’s top-tier AI researchers, as compared to 20 per cent from the US. It will not be too long before China’s economy surpasses the US’s by other measures too. The Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR) predicts it will happen in 2029 (CEBR 2015). If it does, then all this may dramatically change the context for dealing with global economic challenges.

Figure 1.2 Where do top-tier AI researchers come from?

Note: country affiliations are based on the country where the researcher received their undergraduate degree.

Source: adapted from Macro Polo (2020).

Today, the Asia-Pacific region is the emerging command centre of the global economy. China has become the engine that is driving the recovery of other Asian economies from the setbacks of the stagnation of the 1990s. Japan, for example, has become the largest beneficiary of China’s economic growth, and its leading economic indicators have improved as a result. Thanks to increased exports to China, Japan has finally emerged from a decade of economic crisis. By 2020, the US National Intelligence Council (NIC) predicted, China would be an economic powerhouse, vying with the United States for global supremacy. Mapping the Global Future: Report of the National Intelligence Council’s 2020 Project, one of the council’s key reports in December 2004 on the status of ...