Why Tailwheel Airplanes?

On the topic of tailwheel airplanes, people sometimes ask why they are still around anyway. Isn’t the nosewheel design more stable, easier to fly, and just generally safer? Why would anyone want to fly an inherently unstable airplane when there is a greater chance of a mishap?

It turns out that the tailwheel design has some real advantages when it comes to rough or unimproved landing areas. The tailwheel design is lighter, mechanically simpler, and more rugged than the nosewheel design. The propeller has more ground clearance and the tailwheel airplane can handle rougher surfaces and take more abuse than the relatively delicate nosewheel airplanes. Perhaps the tailwheel airplane’s greatest advantage is that on landing it can use lower pitch attitudes and better manage wing lift in a way that is appropriate for off-field work. Additionally, when it comes to ski flying, the tailwheel airplane is a generally better design for reasons that will become evident later on in this book.

It is no coincidence that the tailwheel configuration was the design of choice in the early days of aviation when unimproved landing areas were the norm. It wasn’t until we developed an aviation infrastructure and most flying was done from airport to airport that nosewheel airplanes began to seriously come onto the scene. Today, tailwheel airplanes are still the preferred choice when flying to unimproved strips.

There is another reason why tailwheel airplanes are still relevant in the modern world: they involve a very basic, hands-on kind of flying. With all the improvements of newer airplanes, flying can become a matter of just doing things “by the numbers” or managing the automation, and the old stick-and-rudder airplanes can bring us back to the basics. They keep us engaged with the airplane, focus our attention on basic airmanship, and continually provide opportunities to hone our skills. For this reason, the time we spend in tailwheel airplanes can benefit the rest of our flying.

Aside from their practical benefits, another reason to fly tailwheel airplanes comes down to personal satisfaction. A lot of the old airplanes have a good feel and are just enjoyable to fly.

What about the idea that tailwheel airplanes are less safe? They are certainly demanding of good technique, but as long as we develop and maintain our proficiency, there is nothing unsafe about them. If their demanding nature forces us to hone our skills and focus attention on basic aviating, then in the end they probably make us safer. The nosewheel design has become the standard but it certainly hasn’t made the tailwheel airplane irrelevant or obsolete.

The Preliminaries

When doing a tailwheel checkout, before we get in the airplane, I spend some time talking about what I call the preliminaries: stability, weathervaning, adverse yaw, and angle of attack. This provides background information on tailwheel topics, explains some differences between the nosewheel and tailwheel design, and lays the groundwork for flight training.

Stability

The first topic I cover is the airplane’s yaw stability on the ground and how the nosewheel and tailwheel airplane differ in this respect. Stability has to do with how the airplane responds to a disruption. In the case of yaw stability, if an airplane deviates from a straight path and it tends to straighten itself out on its own with no pilot input, then the airplane exhibits positive stability, which is the case with nosewheel airplanes. On the other hand, if that same initial yaw deviation gives rise to forces that act to increase the deviation—so that left on its own with no corrective action from the pilot the airplane would swing entirely out of control—then the airplane exhibits negative yaw stability, which is the case in tailwheel airplanes.

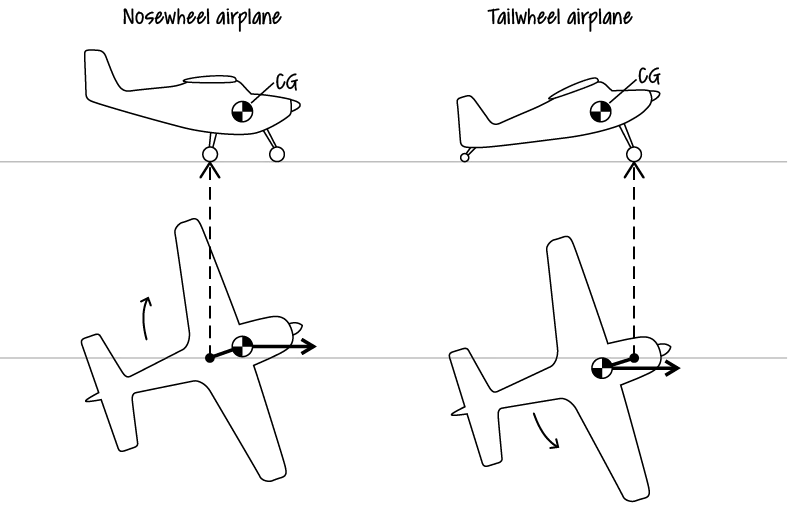

An airplane’s yaw stability on the ground is a matter of the relative location of its main wheels and its center of gravity (CG). The location of the main wheels is important because the airplane yaws about this point. The location of the CG is relevant because the airplane behaves as if its entire mass is located at this point. When the airplane is in motion, the CG wants to continue traveling in its established direction. Figure 1 shows how this works in nosewheel and tailwheel airplanes.

The top of Figure 1 shows the relative position of the main gear and the CG, and the bottom of the drawing shows what happens when the airplane becomes a little crooked on the runway. In both cases, the CG wants to continue moving forward along its previously established direction of travel. In the nosewheel airplane, the inertia acting on the CG acts to pull the airplane back in line, and this arrangement naturally resists any change in direction and tends to be self-correcting to yaw deviations. When the tailwheel airplane with the CG behind the main wheels gets a little crooked, the CG’s desire to keep moving in the direction of travel now acts to increase the yaw. In this case, the greater the yaw deviation, the greater this disruptive force becomes, and the pilot must actively intervene to straighten things out. The pilot correction is best done early, when both the yaw deviation and the necessary corrections are small. The more crooked the airplane is allowed to become, the more aggressive corrections are required to get it back straight, and the airplane can reach a point of no return where it is so crooked that there is no getting it back. At that point, the pilot is just along for the ride and the airplane swings around in a ground loop.

Figure 1. Yaw stability in nosewheel and tailwheel airplanes. The top view shows the relative location of the main wheels and the CG, and the bottom view shows how the airplane’s inertia acts on the CG when the airplane becomes crooked.

Exactly what damage comes out of a ground loop depends on the particular airplane and the speed at which it is traveling. If the airplane is not moving too fast, it might just swing off into the weeds with no damage at all. The faster the airplane is going, the more damage is likely to occur. Every airplane has a particular ground loop characteristic, some of them weather a ground loop relatively well while others are prone to major damage such as a collapsed gear leg, prop strike, bent wingtip, or sometimes even ending up upside-down. In any case, the ground loop is to be strictly avoided, and fortunately with a little knowledge and practice this is easy enough to do.

Before getting into the specifics of how to fly tailwheel airplanes, it is worth discussing the type of control inputs that should generally be used to manage an unstable airplane characteristic. When an airplane’s behavior is unstable, it is easy to aggravate the problem by making inappropriate flight control inputs.

To illustrate this, consider the present case of yaw in a tailwheel airplane. It is not enough to just make corrective rudder inputs; you also have to make them with a good sense of timing. In fact, good timing is a large part of controlling the yaw in tailwheel airplanes.

The first matter of timing has to do with addressing yaw deviations promptly while they are still small. Remember that the more crooked the airplane is allowed to get, the more crooked it wants to get, and the more aggressive action is required to get it back. It makes things easier if you immediately address yaw deviations while they are still small instead of delaying action until the deviations are large. You’ll want to make numerous, small control inputs rather than waiting to make less frequent, large ones.

The second matter of timing relates to how long you keep a rudder correction applied. For example, suppose the airplane begins to yaw left, and you respond with right rudder to straighten it out. If you hold that control input for too long, the correction will bring the yaw to the right of center, and now the instability will take over and the airplane will want to go farther right on its own. Correcting a deviation in one direction can very easily lead to a deviation in the opposite direction. To keep the yaw steady, maintain corrective inputs for just long enough to fix the problem, but not long enough to create a new problem. Fortunately, there is a good reference that will help with the timing: as soon as you see the airplane begin to respond to a corrective control input, use that as a cue to neutralize the input. For example, when you address a yaw deviation with a rudder input, as soon as the airplane’s nose starts to swing back to center then immediately remove the input (bring the rudder back to neutral). This will get you back in the ballpark of being straight and at that point you can be on the alert for the next correction that might be needed.

The net result of these two timing issues is that sometimes your feet have to be in constant motion to keep the airplane tracking perfectly straight down the runway, especially in adverse conditions such as gusty crosswinds. By promptly making an early rudder input at the first sign of a yaw motion and then backing off that input at the first sign of it taking effect, you will find yourself making constant back-and-forth motions with your feet. Sometimes I demonstrate this: while I control the airplane rolling down the runway, I first direct the student’s attention outside and point out that the nose appears rock-steady, then I have them look inside at my feet to see that they are constantly in motion with the numerous and small corrections required to keep the nose steady. The contrast between the steady yaw and the constant motion of small corrections required to keep it steady illustrate an important point about how to fly a tailwheel airplane.

There is one more important thing to mention here: every tailwheel airplane has a distinctive rhythm when it comes to the timing of the control inputs. Things happen fast in some airplanes and you have to make snappy, short-duration stabs with the rudder, while other airplanes move a little more slowly and require more gradual and deliberate inputs. Some airplanes just require a little pressure on the controls while others require larger control deflections. Some planes go astray in quick, darting lunges while others gradually build momentum as they go astray. Every tailwheel airplane has its own personality, and flying it well is a matter of getting tuned into that personality. How you move your hands and feet must be tailored to match the particular airplane’s natural rhythms, and the kind of control inputs that work in one airplane aren’t necessarily appropriate to another. The basic principles are the same for all tailwheel airplanes but each particular type of airplane has its own personality when it comes to the timing of control inputs.

Weathervaning

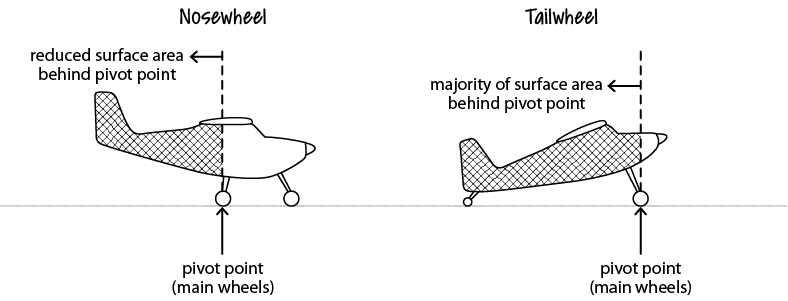

Another element of the tailwheel airplane’s personality is a strong tendency to weathervane in a crosswind. Airplanes weathervane because a greater amount of their side area is behind the main wheels than in front of them, so when a crosswind pushes on the side of the airplane it creates a net force to push the tail to the side and swing the nose into the wind. There is a difference in the weathervaning tendency between nosewheel and tailwheel airplanes; more of the nosewheel airplane’s side area is behind the main wheels than in front of them, but nearly all of a tailwheel airplane’s side area is behind the main wheels. As shown in Figure 2, this greater imbalance of surface area causes the tailwheel airplane to weathervane more strongly than the nosewheel airplane.

Figure 2. Weathervaning in nosewheel and tailwheel airplanes.

A strong weathervaning tendency is not all bad—it really comes in handy when taking off or landing directly into the wind because in those cases it acts as a stabilizing force and helps keep the airplane straight. On the other hand, weathervaning is a real nuisance when taking off or landing with a crosswind. In a crosswind takeoff or landing, weathervaning will pull the nose away from the centerline, and from there the airplane’s inherent yaw instability aggravates the situation. This puts the tailwheel airplane at a double disadvantage, and you will have to exert some effort to keep it straight throughout a crosswind takeoff or landing. Crosswinds are easier in the nosewheel airplane, partly because the weathervaning is not as strong, but also because the nosewheel airplane’s positive stability helps keep it straight.

But don’t be intimidated by the fact that a tailwheel airplane is more difficult in a crosswind. It just means that you have to be proficient at good crosswind technique, and with a little time and effort, this is easy enough to do. You also have an additional tool for yaw control which, when used correctly, mitigates the weathervaning and makes crosswind takeoffs and landings a little easier. This additional tool is the adverse yaw from the ailerons.

Adverse Yaw

Rudder is the primary yaw control, but the ailerons also yaw the airplane in a way that can be used to the pilot’s advantage. Since yaw is important in tailwheel airplanes, pilots should use every resource available to control it.

When the ailerons are deflected, the down aileron creates more drag than the up aileron, and the net effect is to yaw the airplane away from the direction of roll. For example, deflecting the stick to the right lowers the left aileron, which yaws the airplane to the left as shown in Figure 3. Now consider that exact scenario with a right crosswind; the crosswind yaws the airplane to the right, and deflecting the stick...