![]()

1

The Architecture of Medieval Upper Spaces

In order to understand how ecclesiastical upper spaces functioned, we need first to identify them. This chapter therefore serves as an introduction to the spaces discussed in the following chapters. Part 1 of this chapter introduces the architecture of medieval stairs, looking at their design, construction, aesthetics and finish. The second part is an exploration of upper spaces, including upper chambers, wall-passages and galleries, in medieval monastic, parochial, and some secular architecture. From this point, frequent reference is made to what we shall call the ‘Canterbury case-studies’, a series of medieval ecclesiastical buildings within a 20-mile or so radius of the metropolitical Cathedral city and World Heritage site.1 Pride of place naturally goes to Canterbury Cathedral, an exceptionally well-documented and largely intact suite of medieval buildings of the very highest quality. First among the parish churches is St Leonard, Hythe, a very ambitious church nestling on a steep hill by the south Channel coast, which boasts a full three-storeyed chancel, begun, if not completed, in the thirteenth century (Fig. 1.1).2 To a great extent, stairs, wall-passages, galleries and upper rooms deserve to be seen as creating networks of upper spaces which it may seem somewhat artificial to separate out. However, it is useful to introduce them in a systematic way. A hint of the importance of stairs in medieval architecture is glimpsed in the Regulations concerning the Arts and Crafts of Paris of 1258 which stipulate that no-one could practice their craft after Nones had been rung at Notre-Dame on Saturdays, except when closing a vault or a stairwell.3 These humble but very essential features therefore repay closer investigation first.

Part 1: Stairs

Design

Medieval stairs took several different forms. Some are in long, straight flights, hereafter termed ‘linear’, such as the Night Stair at Hexham Abbey, Northumberland (see below). Other stairs are annular in form, circling around the inside of a large round building, such as that in the baptistery at Pisa, Italy. Most take the form of spiral stairs (vices, or newel stairs) which wind around a central newel pillar, of which there are surviving examples from the late eighth century onwards. The Vis de Saint Gilles, built in the bell-tower at the abbey of Saint-Gilles, Languedoc, France in 1142 was particularly famous for its complex vault geometry in the medieval period, and it remained an object of study well into the Early Modern era.4 Indeed, the stair not only attracted admiration from across the Continent, but apprentice masons even created models of it to show their skill.5 As David Parsons has pointed out, vices are technically helical not spiral, although contemporaries imagined and represented them as spirals (such as on the St Gall Plan of c. 820), and so the original name endures. A specialised form of vice is a double-helix, of which there are some English examples dating from the fourteenth century. Contemporary writers frequently resorted to zoomorphic terms to describe such architecture, hence cochlea (snail shell), for spiral stair, and testudo (tortoise), a vault.

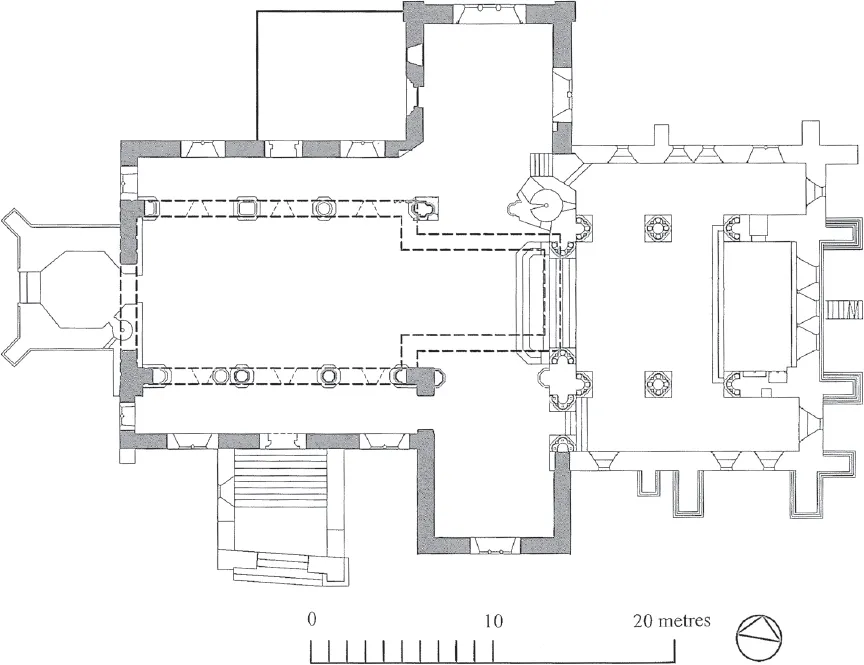

Fig. 1.1 St Leonard, Hythe, Kent (after Berg & Jones, 2009)

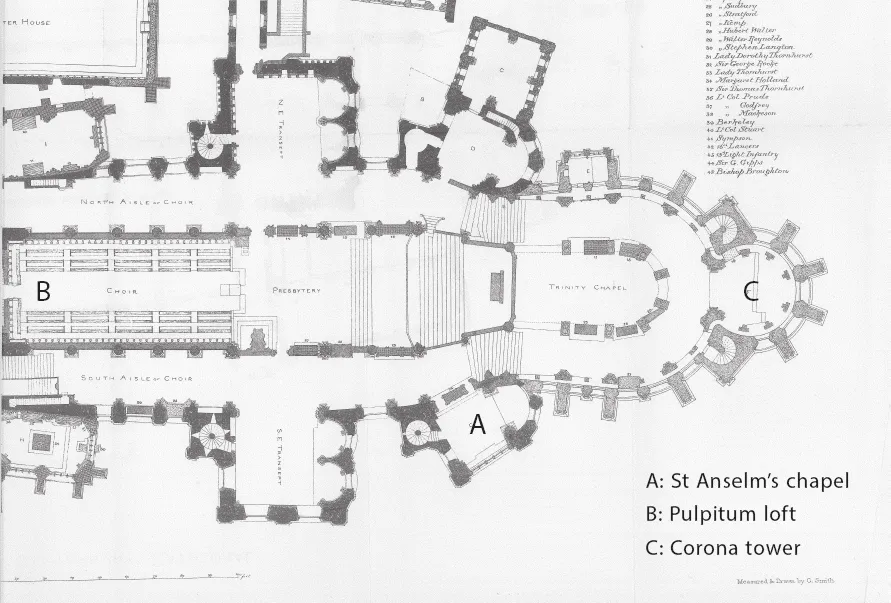

Spiral stairs exhibit two main forms depending on their date. In the Romanesque form (up to c. 1230), the newel and tread consist of separate blocks, all supported by a semi-circular barrel-vault underneath (Fig. 1.2). A widespread design change took place around 1230, whereby each tread was now fabricated from a single block of stone (or winder) incorporating the newel section in the shape of an eccentric keyhole (Figs. 1.3 & 1.4).6 The reasons for this change from barrel-vaulted to monolithic form probably included speed of construction, economy of effort, and greater structural strength. Close examination of the case-study stairs can cast fresh light on existing theories of how this formal change from Romanesque to Gothic design took place. David Parsons has speculated that the later type was anticipated by the use of ‘tailed’ newel sections, which incorporate an attached bearing surface for the step.7 However, there is no evidence to suggest that tailed newels appeared immediately prior to c. 1230, and they may simply have helped to create a stronger construction bond, as seen in the alternation of long- and short-tailed newel stones in the remains of the Infirmary vice at Canterbury Cathedral.8 Instead, the design transition from barrel-vaulted to monolithic stairs was probably much more complex and subtle than usually assumed. Near-monolithic steps, missing only the newel projections, are found in the lowest courses of several twelfth-century vices, such as those in St Andrew’s chapel and the Corona tower at Canterbury Cathedral (Fig. 1.5).9 Furthermore, the top steps of some Romanesque stairs (such as the Chillenden chambers vice at Canterbury and the west tower vice at St Mary, Brook, Kent) are in the form of monolithic blocks. This suggests that monolithic steps may first have been used to cap barrel-vaulted vices in the Romanesque period, and later extended to whole staircases in the Gothic.10

Fig. 1.2 Barrel-vaulted vice in the north-east transept, Canterbury Cathedral

Fig. 1.3 Typical monolithic step (ex situ), from ruined tower house at Limerick, Co. Limerick, Ireland

Fig. 1.4 Steps of later medieval form at St Mary & St Ethelburga, Lyminge, Kent

The Anglo-Saxon scholar Harold Taylor identified the presence of double-height newel sections as one of the principal diagnostic features of an Anglo-Saxon vice.11 This theory is based on a handful of probable (but contested) possible late Anglo-Saxon stairs, such as that in the west tower at Hough-on-the-Hill, Lincolnshire. This is directly relevant to date of the west tower at St Mary, Minster in Thanet, Kent, which has been the subject of debate, with arguments put forward for both pre-and post-Conquest dates.12 It seems to have escaped attention that this vice incorporates double-height newel sections, making a late Anglo-Saxon date for this vice and tower a realistic possibility (Figs. 1.6 & 1.7). Minster became a manor of St Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury around 1030, and it is tempting to speculate that the tower might be a remnant from a church built at this time. However, it is also clear that the double-height newel technique was by no means confined to the Anglo-Saxon period. Long newel stones are used in the large newel drums in the late twelfth-century Corona vices at Canterbury Cathedral, and also in the first-floor half-vice in the Gatehouse at Dover Priory, which is thirteenth-century in date or later.

Fig. 1.5 The choir at Canterbury Cathedral, drawn by G. Smith (1883)

Timber ladders are another important form; indeed, they were traditionally the sole method of access in Irish Round Towers. Panels from the Bayeux Tapestry show that wooden ladders with triangular wedge-shaped steps were certainly known at the time of the Conquest. A famous example is in the west tower at St Mary, Brabourne, Kent. The tower itself is Romanesque, and the ladder has been dendrochronologically (tree-ring) dated to the mid-fourteenth century.13 The key elements of these medieval ladders are a series of triangular treads pegged into two parallel rails, typically set at quite a steep angle in the building, and often provided with a handrail. While sometimes claimed to be unique, this stair is one of a series of timber tower ladders in the locality, with comparable examples in East Kent at St Mary, Fordwich (starting from first-floor level); the extra-parochial church of St Nicholas’ Hospital, Harbledown; All Saints, Whitstable; St Clement, Old Romney; and St Mary, Westwell, as well as further afield at St Mary, High Halden (Fig. 1.8). There are also ladders providing access to porch chambers, such as that at St Nicholas at Wade in the same county, and there were probably once many more timber stairs which have not survived. The reasons for selecting timber over stone are not readily apparent, but could include ease of transportation, lightness, and simplicity of construction.

Fig. 1.6 The west tower at St Mary, Minster in Thanet, Kent

Fig. 1.7 Double-height newel stone (top left) in the spiral stair at Minster

Fig. 1.8 Wood ladder in the tower at St Mary the Virgin, High Halden, Kent

Stairs of all types might be built in greater churches in the west front, in porches, transept returns and presbyteries, the latter often beginning at first-floor level, although their location in the building is often subject to variation. Stairs occasionally occupied the centre of major Crossing piers, as at Finchale Priory, County Durham, although this was perhaps too much of a structural risk to become widespread. In parish churches, stairs correspond closely to the upper-storey feature to which they relate, generally being found in a corner of the tower, to the north or south of a chancel arch, and in an interior angle of a porch. The north-west chancel pier at St Leonard, Hythe, Kent, is a very unusual location for a stair in a parish church. At Boxgrove Priory, Sussex, the access stair to the clerestory is found in the aisle. At Elkstone, Gloucestershire, the newel stair at the entrance to the chancel provides access to an upper chamber, although other chancel upper chambers in the west of England such as Compton Martin, Somerset, had no access from the inside, with an exterior doorway requiring a ladder. Medieval stairs are easily detectable from the outside by their characteristic long and narrow ‘arrowslit’ windows, whether square-headed, round, or arched. Most of these windows, especially Romanesque examples, are widely splayed on the inside, to allow in the maximum amount of light. This was an aspect of the stairs at St-Bénigne, Dijon, France singled out for praise by its anonymous medieval chronicler, and the Corona stairs at Canterbury Cathedral are also well-lit by natural light.14

Construction

Stairs are particularly revealing for the archaeological evidence they contain, especially of different stone types and materials. In the Canterbury case-studies, imported Caen stone ashlar from France was often used for newel stones (as at Hythe), while local ragstone rubble readily found its way into stairwells.15 In the Cheker vice at Canterbury Cathedral, some of the window-jambs and voussoirs are made out of bright white chalk, in contrast to St Leonard’s Tower, West Malling, Kent, where light tufa ashlar was used throughout. The west tower vice at St Mary, Minster-in-Thanet, Kent, has newel stones carved from a light orange sandstone. Some choices of stone were doubtless made on the basis of convenience or practicality. Some of the steps at St Mary, Kenardington, Kent, clearly had a marine origin, as the undersides preserve clusters of medieval barnacles. At St Leonard, Hythe, a special hard dark grey stone (probably from the Hythe Beds of Lower Greensand) was used in the chancel vice by the rood loft exit and in the linear steps beyond the chancel arch leading down to the south triforium and so...