![]()

SECTION I

THE EDWARDIAN

AGE AND ITS

HOUSING

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Edwardian Times

Contrast and Tradition

FIG 1.1: SION HILL HALL, THIRSK, YORKSHIRE: One of the last great houses, built just before the First World War by Walter H. Brierley, often referred to as the ‘Lutyens of the North’. The steep pitched roof with overhanging eaves, prominent but plain chimneys and the symmetrical façade were inspired by late 17th and early 18th century houses, but were arranged in new forms by both architects.

Literature, films and photographs of the Edwardian period give us today a vision in sepia of a long lost imperial world resplendent in pomp and ceremony, with poignant images of weekend parties and lazy days by the river all set in a seemingly endless summer. It appears from this distance that it represented the final flowering of the British Empire, a confident time celebrated in magnificent buildings and rousing anthems, led by ambitious men and world leading innovators, with a population that spent a large proportion of their earnings on hats. In reality, however, it was a period of anxiety with the realisation that all was not well with our colonial acquisitions, the economy and the conditions and social status of too many of its inhabitants. It was a time of great contrasts not only between rich and poor but also between the embracing of inventions and the obsession with preserving the past. Far from being a decadent, leisurely decade it was one in which ground breaking new legislation and political ideas were laid down, creating the foundations for the 20th century. And in reality the summers were not that good either!

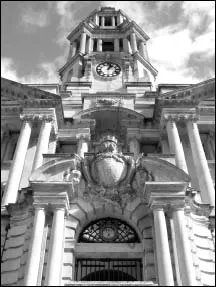

FIG 1.2: STOCKPORT TOWN HALL, GREATER MANCHESTER: For major Edwardian public buildings there was a rejection of the red brick Gothic that had been popular in the mid to late Victorian period and a return to classical architecture, in this case the flamboyant Baroque of the late 17th and early 18th centuries (see Fig 1.5).

The Fall of the Landed Classes

The accession to the throne of the notorious and disreputable Prince of Wales in 1901 played its part in welcoming in a lighter, more relaxed attitude to life especially among the younger generation. Gone was the distant and austere Queen; now there was a new King whose fashionable, lavish and extravagant lifestyle fulfilled the public’s image of an imperial monarch and fuelled a fascination with the aristocracy. The super-rich seemed to be on an endless cycle of long weekend parties, great shoots and gambling, their year based around the London Season from spring to summer, then sailing at Cowes or off to the French Riviera before returning for the Glorious 12th and the Hunt (during a three-day shoot at Sandringham in 1905, we are told that the King and his guests managed to shoot down more than 6,000 birds).

FIG 1.3: SANDRINGHAM PALACE, NORFOLK: Purchased in 1862 by the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, as a country estate for shooting parties and entertaining, it was largely rebuilt a few years later (the left-hand part in this view) and extended in 1892 (the right-hand side). This sociable monarch, although popular with the working classes, was seen as disreputable by the more serious minded middle classes and it was only his role of country gentleman on his Sandringham estate that gained their favour.

However, not all gentlemen were able to enjoy this lifestyle, especially those whose wealth had been dependent upon rents from their estates, money that dried up as a result of the halving of land values in the wake of the agricultural depression of the late 1800s. These difficulties were intensified by the King’s own government, which from the late 19th century was elected by an increased proportion of the population, loosening the landed gentry’s traditional grip on power (Asquith who became Prime Minister in 1908 was the first to do so without a country seat). With the introduction of – and subsequent increases in – taxes on the super rich and their property, including death duties, many were forced into cutbacks, selling their town residences and retreating to the country, or at worst losing their seat completely. More than fifty great houses were demolished or abandoned in this period. There was, however, plenty of new money floating around, ready to snap up a bargain title, house and estate. As the effects of the slump in farming and the ‘boom and bust’ nature in elements of the economy were patchy, there were some who did well in this period – especially those in finance, who were ready to buy into the aristocratic image.

The Liberal government that came to power in 1906 intended to use much of the revenue from taxing the rich to pay for new social policies. Although the welfare state is associated with the post Second World War period, the first pensions and national insurance schemes were actually introduced by Lloyd George in his 1909 budget. An after effect of this, however, was the Parliament Act, which was required in order to force this controversial package through the Lords and which took away their right of veto, further crippling the power of the aristocracy.

FIG 1.4: CASTLE DROGO, DEVON: Regarded as the last major country house built in England. It was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens for Julius Drewe, the founder of the Home and Colonial Stores, in 1910–11 but was not completed until 1930 and then on a reduced scale.

There were, however, many other problems facing the Government at the time that were not so easily solved – the rising power of Germany, Home Rule for Ireland and, closer to home, the Feminist Movement. As the 20th century dawned, women became the majority of the population, they had improved health and many made the conscious decision to have smaller families and improve their lot. Around three-quarters of women between 15 and 34 years of age worked but only an exceptional few had professional jobs, most being restricted to traditional female trades like domestic service, though an increasing number were finding new opportunities in teaching, nursing, the Post Office and the new light industries. The frustration with this situation was most famously voiced by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters who broke away from more conservative feminist groups and campaigned with increased violence, which peaked in the years just before the First World War, a time further disrupted by widespread industrial unrest.

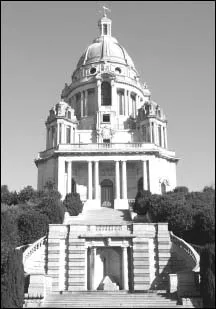

FIG 1.5: ASHTON MEMORIAL, LANCASTER: This huge Baroque style, domed memorial was built between 1904 and 1909 to the designs of John Belcher and was paid for by Lord Ashton, a local industrialist and millionaire.

Middle Class Growth and Anxiety

The fear of disruption and revolution among the working classes had long been of concern to the middle classes, and now added to this were worries about foreign competition and moral decline, such that leading philosophers and economists predicted worse times ahead. Despite this underlying gloom the position of the professional classes was strengthened in this period with growing political influence and financial success, partly through the doubling of exports and Britain’s command of the world financial markets, to the extent that the gap between the middle and upper classes closed and could sometimes merge. From the managers down to the clerks there was more money to be spent upon the home and in the rapidly increasing array of shops that had suddenly grown over the past fifty years to cater for the aristocratic aspirations of the middle classes.

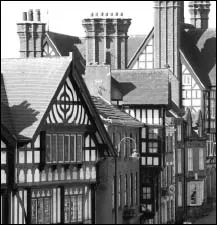

FIG 1.6: ST EDWARDS STREET, LEEK, STAFFORDSHIRE: These late Victorian houses, shops and flats are cloaked in a reassuring traditional style with Cheshire black and white timber work and Tudoresque tall brick chimneys, despite this being a modern progressive industrial town at the time.

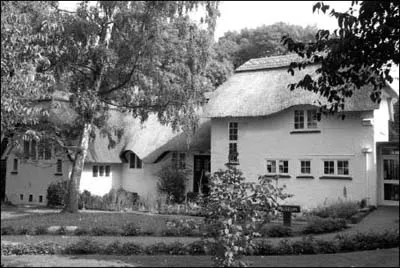

FIG 1.7: THE FIRST GARDEN CITY HERITAGE MUSEUM, LETCHWORTH: Some architects used features from the much idealised English country cottage, as in this example with thatched roof, rendered walls and tiny casement windows designed by Barry Parker in 1907 and now the home of the First Garden City Heritage Museum.

The Edwardians were also surrounded by a wealth of technological advances from the past few decades, including cars, aeroplanes, the wireless and telephones. Electricity was now becoming available in more homes, its clean light and ability to power a wide range of modern appliances appealing to the middle and upper classes obsessed with hygiene and struggling to find domestic servants. In this world of machine-made products and shockingly new devices, there was a peculiarly English rejection of modernity, an obsession particularly amongst the middle classes for a mythical rural past, which had a huge effect upon interior design and architecture. This fashion for handmade crafts, rustic cottages and country ways was further enhanced by a general mistrust amongst the populace for all things Continental; even Impressionist artwork was mocked or ignored, making developments in design rather insular and backward looking.

FIG 1.8: HAMPSTEAD GARDEN SUBURB, LONDON: The more modest red brick country house of the late 17th century was the source for what developed into the Neo Georgian style as used in this institute and school building.

The ideal life for the middle class family was still formalised, ordered and guided by etiquette, taught through a now wider range of books, magazines, schools and universities. Social occasions and public celebrations were embellished with pomp and deliberately elongated; all classes could take part, if only so that their position in society could be reinforced. Despite the growth and prominence of the urban middle classes they still only accounted for around 15% of the population at the turn of the century.

Working Class Life and Poverty

Life for the urban working classes, the majority of the population, had improved in many ways over the previous fifty years. The average family at the turn of the century could expect accommodation spread over four rooms rather tha...