![]()

SECTION I

THE HISTORY

OF THE

VICTORIAN

HOUSE

![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Background

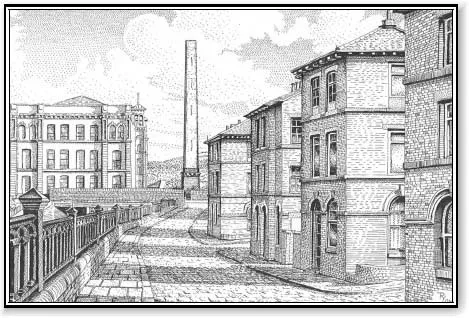

FIG 1.1: Saltaire, West Yorkshire: In 1853, Titus Salt did as many entrepreneurs of the day were doing and opened a new mill which incorporated numerous separate manufacturing processes for the first time under one roof (rear left of picture). Few, however, went on to build a complete village with sanitary housing, school, hospital, library and church for his employees, a rare benevolent action which took place over the 1850s and 1860s. The village was named after Titus ‘Salt’ and the River ‘Aire’ upon which it stood.

The impression left by Victorian England is one of great contrasts. There is the perceived image of religious adherence and high family values, yet there was still child labour, poor public health and disease. We marvel at so many great inventions and impressive engineering projects, but forget the high loss of life in their creation and the intolerable working conditions of those who had to use them. We can still visit the gleaming steam engines and pristine country houses today, but without the filthy environment, smog and soot in which they originally stood. From this distance, the period appears a time of consistent financial success and international glory. However, this simple view masks the fluctuations, failures and depressions which struck at differing times throughout Victoria's long reign.

These same contrasts exist in their houses. Those which survive today are generally spacious and well built from good quality materials, with highly decorated façades. Yet the homes in which the majority of the working population lived were unhygienic, tiny and often poorly built, creating slums which have long since been flattened. Our image of Victorian buildings is therefore slightly skewed as so much of what was bad has been pulled down, while left standing are the quality structures or those with the space to permit adaptations for modern living.

When criticising modern housing, compared to the more decorative and better quality Victorian product, it is worth bearing in mind that a skilled worker who today might expect a three-bedroom semi with garden and all mod cons, in the 19th century would have sufficed with a two-bedroom terraced house and yard. Likewise, a small terrace house on the bottom of today's property ladder would have been a good-sized family home for a skilled factory worker in the 1850s.

The Victorian house has become popular again since the 1980s, especially compared with some of the plain and apparently flimsy housing on offer from the 1960s and 1970s. However, it should be noted that nearly three times more houses were erected in these decades than at the peak of Victorian building around 1900.

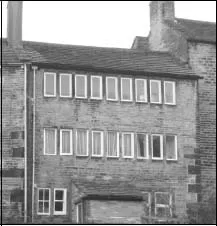

FIG 1.2: Weavers’ cottages in Holmsfirth, with the distinctive rows of windows illuminating the top workshop floors.

Although these points are aimed at removing our rose-tinted glasses before proceeding, this book is written not only as a hands-on practical guide to recognising and understanding Victorian houses but also as an enthusiastic celebration of these colourful, eccentric, eclectic and quality products of the industrial age. They were built to house a population which grew from eleven million in 1801 to thirty-two million a century later. Our story will begin with a look at where this bulging population lived.

Town and Village

Victorian England had a booming population, one that had been growing since the mid 18th century (principally due to a fall in the death rate of the very young) but which doubled between 1841 and 1901. At the same time, the number of people in each household dropped which, coupled with an expectation of more privacy and independence, led to greater demand for housing.

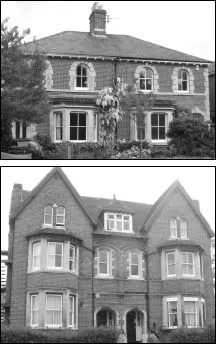

FIG 1.3: Examples of Victorian semi-detached houses in North Oxford, with an Italianate style (top) and Gothic style (bottom), both dating from the 1860s and 1870s.

The type and location of new building was to be greatly affected by the emergence of a new and increasingly influential social group – the middle class (although even by 1890 it accounted for less than 15% of the population). Those with a good education, a skilled job and a desire to demonstrate their success looked away from the cramped old Georgian terraces in the heart of the towns and cities. Instead, they were attracted to new developments on the edge of the urban area where the rapidly growing railway network still gave them easy access to the work place. These suburban estates, or suburbia, contained a variety of building types and sizes depending on whether they were aimed at lawyers, managers and doctors or clerks and tradesmen. The three commonest forms were the villa, the semi and the terraced house. Originally, villas were large detached estate houses in a landscaped setting but by the later 19th century the name could refer to almost any properties which were reasonably sized, detached or terraced and with a garden. Semis were not common yet and were often styled at this date to appear as a single detached house and hence raise their status. The bulk of suburban housing was terraced, usually one room wide and two deep, with a corridor running off from the front door, but as with all these housing types they became generally larger as the period went on, with more adaptations and extensions.

The growth of suburbia represented the new middle class's aspiration to appear respectable and at the same time to be separated from the lower classes. In the towns and cities, the poor would no longer live alongside the educated professional. Instead, the ordinary workers moved to the old buildings in the centres of towns and cities that had been vacated by the middle classes. These buildings were often divided up and filled with a number of families so that the landlord could still achieve a reasonable income despite the lower individual rents.

New housing created for the poor was crammed into small plots and usually set around courtyards or along narrow, muddy back streets with, in the early years, no proper drainage or sanitation and only a communal water supply at best. The houses were either small terraces with through passages or back-to-backs, which were common in the industrial areas like Sheffield, Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham and Nottingham. These were terraced houses of one room depth which backed directly onto an identical row behind. They had no rear door and were surrounded on three of their four sides (figs 1.4 and 1.5). They were understandably unhygienic and, although as conditions improved local authorities forbade their construction, many were still being built in areas like Leeds right up to the end of the 19th century.

However, by 1900 conditions had improved and the poor working family who were likely to have lived in just one room when Victoria came to the throne could expect a small two-up two-down house by the time she passed on. A few fortunate workers might find themselves in the employment of a philanthropic individual who, inspired either by religious benevolence or a desire to improve efficiency and create social stability, would build good quality housing for their staff. These new housing estates had proper sanitation, purpose-built churches, libraries and green spaces but rarely pubs! Famous examples include Saltaire, outside Leeds (fig 1.1), Port Sunlight on the Wirral and Bourneville to the south of Birmingham.

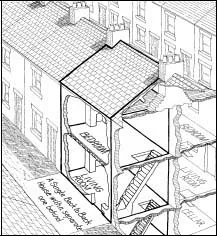

FIG 1.4: A cut-away view of one type of back-to-back house, with a cellar for coal, a single living room and a bedroom above.

FIG 1.5: Restored back-to-backs in Inge Street, Birmingham (National Trust). Although they received a bad press in the 20th century, in their day they were a big improvement upon the single rooms working-class families had to share in many towns and cities (houses facing the street on the left and houses facing into the courtyard on the right).

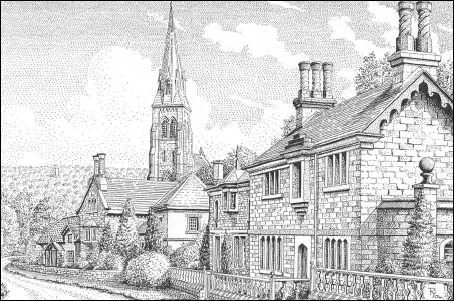

FIG 1.6: Edensor, Derbyshire. When the 6th Duke of Devonshire decided Edensor rather spoilt the view from Chatsworth House, he had the village flattened and a series of individually designed, rather eccentric stone houses built out of sight in the late 1830s. Many of the designs in this model village were inspired by the influential Encyclopedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture and Furniture by J.C. Loudon.

Despite the fluctuating drift of rural workers into the industrial towns and cities, the population of the countryside remained steady or even increased in the first half of the Victorian period. This was principally due to new settlements or extensions to existing ones being built to house workers for canals, railways, mining, quarrying, brickmaking and similar industries. Many villages in the later 18th and early 19th century became controlled environments, with any remaining common land enclosed and selected estate staff and tenant farmers tied to what was often the better quality housing. This process could also result in the eviction of casual agricultural labourers who could either try their luck in industry or struggle to find rural accommodation and end up in slum conditions worse than those in the cities. The modern image of the ideal English village, complete with a church, shop, school and rustic cottages set around a green, took shape in this period. There were few neat and trim rural settlements with these facilities before the 19th century.

The most notable aspect of rural housing from the late 18th century through to the second half of the 19th is the model villages erected by landowners to house their estate workers. Their motive for providing new accommodation was less likely to be benevolence than the improved efficiency of their estate or to make a more attractiv...