eBook - ePub

Timber Framed Buildings Explained

Trevor Yorke

This is a test

Share book

- 80 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Timber Framed Buildings Explained

Trevor Yorke

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Timber framed buildings, whether they are medieval halls, barns, grand houses, or picturesque cottages, form one of the most delightful features of our historic towns and countryside. They catch our imagination as we admire the skill and craft of the carpenters who created them, with a strength and quality that has seen many of them survive for over six centuries. Using his own photographs, drawings and detailed diagrams, Trevor Yorke helps us to understand what such buildings may have originally looked like, the challenging technology behind their construction, how they have changed over the years, and the details by which we can date them. He also lists some of the prime examples that are open to the viewing public.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Timber Framed Buildings Explained an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Timber Framed Buildings Explained by Trevor Yorke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architettura & Storia dell'architettura. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitetturaSubtopic

Storia dell'architetturaSECTION I

A HISTORY OF TIMBER FRAMED BUILDINGS

CHAPTER 1

| Definition and Origins |  |

FIG 1.1: LITTLE MORETON HALL, CHESHIRE (NT): This most famous of timber framed houses was begun in the 15th century. The whole of this picture (the three-storey building) shows the south range, built a century after the north and east range. The projection next to the bridge is the entrance porch and the long row of windows along the upper floor, the long gallery. Outwardly, it appears as a large substantial structure, yet once inside you find it is formed from a ring of thin rectangular boxes arranged around a courtyard.

Ask most people what a timber framed building looks like and they will describe an old house with black wooden beams, white panels between and a tiled or thatched roof above. This distinctive form, unique to this island, has in the past century been an icon of our countryside, featuring on countless images of rural England and attracting millions of visitors to the finest remaining examples. Before looking at them in detail we first need to put them in context. What date are the earliest buildings, when did they fall from favour and what exactly do we mean by timber framing?

What is a timber framed building?

A timber framed building is one in which a principal framework of vertical and horizontal or inclined beams form the main load-bearing support for the upper floors and roof. The infill between them and any outer cladding of stone, brick, tile or timber is purely to weatherproof the structure and to change its outward appearance to suit the whims of fashion. Each wall of the structure is a separate frame, which was prefabricated before being raised or reconstructed in position and linked together. The individual parts were connected by different joints, each one designed to counter the forces applied to it through its shape and the inclusion of wooden pegs (later buildings used iron bolts and straps).

The carpenter had to select timber of suitable thickness to support the main frame and the additional load imposed upon it from fittings and people, falls of snow on the roof and the weight of the building materials themselves. He also had to account for sideways pressure from wind and movement in the foundations and so inserted diagonal struts and braces to resist these. The breadth of timber, the size of the panels, and the patterns formed in each of these frames are the most distinctive features of the building, seen from the outside, which can help to arrive at an approximate date.

FIG 1.2: A view through the side of a medieval timber framed house, highlighting in black the elements that are resisting a force applied in the direction of the arrows. In A the posts take the weight applied vertically from the roof covering, rafters and floor, in B the horizontal beams resist the spreading effect of the roof and in C the angled struts stop the whole toppling over in a side wind. In the latter example the timbers are forming a triangle, which is the one geometric shape that cannot be distorted and is key to keeping timber framed buildings rigid.

The key problem facing builders in the past was how to hold up the roof and in our wet climate a steep pitched type covered in thatch, stone or clay tiles was the traditional form prior to the Industrial Revolution. If you have ever tried to stand two playing cards up by leaning them against each other on a table you will soon realise that they have to be nearly vertical (like a steeple) before they will stay in place; any angle less than this and their bottom edges simply push outwards and they collapse. In effect this is what a roof is trying to do to the walls of the building below and the structure has to be designed to resist this force and the total weight of the rafters and covering.

In traditional timber framed construction this was achieved by generally using steep pitched roofs (the angle depending on the weight and rain shedding properties of the covering material) and different types of roof truss or arrangement of posts and beams, which hold the rafters up from beneath and tie the bottom edges so they cannot push outwards. Their form varies through time and in different regions. When trying to discover the origins of a building it is these hidden structures in the loft that experts seek to ascertain its original dimensions and form.

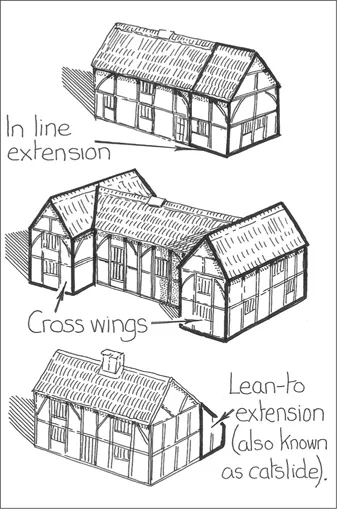

Most timber framed buildings prior to the late 17th century were built one main room deep and were rectangular in plan (there was a limit to how big a gap a horizontal beam could cross before sagging and breaking). This basic form was subdivided into bays, each one being the space between the principal load-bearing posts (see page 6). Any additional space required could be created by extending this form lengthways, but more often carpenters added wings across the ends or built a lean-to structure along the rear (see Fig 1.3). In larger buildings the structure could have aisles along each side to increase space or have its parts arranged around a courtyard, outwardly appearing as more substantial but still having its individual parts only one room deep (see Fig 1.1).

FIG 1.3: Common methods of extending a basic timber framed structure at a later date. The beauty of a framed structure is that these extensions are easily fitted and add to its stability; cross wings at right angles resisted wind pressure applied to the ends of the original building and catslides propped up the main walls to counter the spread of the roof.

Why build in timber?

Despite the close proximity of suitable stone and skilled brickmakers, timber framed structures were still the dominant form of building across the country well into the 17th century. This was mainly because these alternative forms were very expensive. There were few permanent quarries, most local ones being opened for just a single major project, and masons tended to congregate around principal cities and the cost of their services were out of the range of even some lords of the manor. Bricks were handmade to order on site, the skills required making them a costly material, that was generally restricted to the eastern and south-east counties until the later Tudor period and was still not common in the west until the 18th century. It was also difficult to move these products any distance, roads were poor and rivers limited in scope, so materials and skilled workmen were generally supplied from the locality, creating vernacular forms of building. Because reliable sources of wood and the knowledge and tools required to work it were widely available, timber framed structures – usually with roofs covered in equally abundant thatch – were the type that most people lived in until the 17th century and, in some rural areas, beyond.

FIG 1.4: THE ROEBUCK, LEEK, STAFFORDSHIRE: Legend has it that this pub dating from the 1620s was moved from Shropshire some 40 miles away. Although these prefabricated structures could be disassembled, the transporting of hundreds of heavy beams and posts over this distance is unlikely with such poor roads. It would be easier and more cost effective to build with local materials and methods of construction passed down from father to son and the vast majority of timber framed buildings were of vernacular style.

When did timber framing first appear?

Man has always used timber in the building of structures since he first started clearing woodland after the last ice age. However, in most prehistoric examples a structural framework with carpentry joints was not used; an Iron Age round house, for instance, had long poles held in position by a timber ring to form a conical roof, which stood upon low walls of stone, clay or posts.

The Romans certainly used timber framed houses even in their towns and cities. New research is showing that earlier calculations of population may have been wrong because archaeologists underestimated the numbers of these buildings as they did not always leave foundations in the ground. During the Saxon period forms of construction from Scandinavia and Northern Europe seem to have been adopted with vertical halved t...