![]()

WHAT IS GOTHIC?

Gothic architecture is characterised primarily by the use of the pointed arch. Although it is associated with medieval churches, abbeys and cathedrals, and the revival of this style in the 19th century which will be the focus of this book, the pointed arch is a constructional tool not restricted to these periods. As G. E. Street, one of its leading Victorian advocates stated, ‘Gothic ... is emphatically the style of the pointed arch and not of this or that nation, or of this or that age’.

However, when his generation of architects studied the buildings of Europe built from the 12th through to the 16th century they were inspired by more than just this more flexible form of arch. The fact that structural elements like buttresses were left exposed on the exterior of medieval churches and, in many cases, embellished with carvings, was an honesty in construction in stark contrast to the Classical style of buildings which was dominant in the early 19th century. The stone and brick used was left in its natural state and, if decorated, was only done so in patterns formed from different coloured types rather than the stucco-covered brick houses which imitated fine masonry in most Victorian cities. The way in which medieval builders arranged the elements of their buildings to suit the requirements of each part, with little concern for the overall appearance, inspired the Revivalists to create asymmetrical façades and free the interior from the restrictive rules of symmetry which had dominated architecture through the 18th century. Inevitably they also used many of the other details which they noted on these medieval buildings, such as battlemented walls, gable ends, pinnacles and towers, not simply copying them but adapting the forms to modern use.

This Gothic Revival from the 1840s through to the 1870s was more than just a passing fashion in building. The nation and its expanding empire were searching for an identity, one that was home-grown rather than inspired by Ancient Greece or Rome. In art and architecture they found it on their doorstep in the soaring cathedrals, colourful paintings and illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages. With the rapid changes in society and the effects of the Industrial Revolution, an enfranchised middle class growing in influence sought new moral codes and rules and through their rather rose-tinted view of medieval Britain found a time of romantic chivalry, religious adherence and honest craftsmanship. This would inspire not only the ideal Victorian family and the churches they would worship in but also the style of houses they thought fit to live in. Artists and critics began to highlight the faults with the factory system and the poor quality in the design of the goods produced. They recommended the approach of medieval craftsmen who stylised subjects rather than trying to copy them. They began to see an answer to the evils of the Industrial Age in the working practices of guilds and craftsmen from the Middle Ages, although it would not be until later in the century that the Arts and Crafts movement turned the theory into reality.

FIG 1.2: The Gothic Revival was most visible in the huge public buildings constructed in towns and city centres during this period of urban expansion, as in these examples from Liverpool, Manchester and Bradford.

Before looking at Gothic Revival architecture, the housing produced in imitation of it by builders, the characteristic details on the exterior and how it shaped the inside of the Victorian home, we need to go back and briefly explain where the style originated and why it was brought back to life.

Origins

The Romans are credited with developing the arch (the Greeks only had columns and horizontal lintels to form structures). However, the semicircular form the Romans used on their Classical buildings was limited in that to make it span a wider space it had to become higher in proportion which was often not convenient. For a bridge or wall this meant that it was usually composed of a series of small arches rather than just a few large ones. Saxon and Norman masons used the same principle in their churches and castles, with very thick walls pierced by small round arches which, although not elegant, have survived through their sheer mass of stonework.

It was only in the late 12th century that a new idea, first seen at Durham Cathedral, developed further in France, and then used by Cistercian monks in the new abbeys they were building in England, was introduced – the pointed arch. This simple device composed of two sections of a larger arch meeting at a point at the top was more flexible in that it could be made wider or thinner like a hinge, without greatly affecting the height of the structure. Its use in buildings over the following three centuries gave master masons greater freedom and, combined with the development of stone ribs, wooden trusses and external buttresses to carry the load from the roof, enabled walls to become thinner and openings larger, thus transforming the interiors of churches and cathedrals into the glorious spaces bathed in colourful light which we admire today.

FIG 1.3: Saxon and Norman masons used round arches (right) but by the early 13th century the more flexible Gothic pointed arch (left) had been adopted. Note the column on the left is thinner than the pillar in the centre as the use of trusses and buttresses meant wall thickness could be reduced.

However, on the Continent during the 15th century, architects were rediscovering the works of Classical antiquity and applying their principles to new buildings. This Renaissance which would affect all forms of art and education changed the approach to building, with the proportions and symmetry of a façade calculated on paper plans rather than scratched on a floor by experienced Gothic masons. In fact, it was in a book written in around 1550 by the Florentine Giorgio Vasari about the work of these new Classical architects that the word ‘gothic’ was first used. He devised it as a derogatory term, comparing medieval buildings to the Goths, the Northern European tribes who overran the Roman Empire in the 5th and 6th centuries, ‘Then arose new architects who after the manner of their barbarous nations erected buildings in that style which we call Gothic’.

The arrival of the Renaissance in Britain during the first half of the 16th century coincided with the establishment of the Church of England and the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Gothic buildings were being stripped out or demolished and once there was some form of religious and political stability in the reign of Elizabeth I, new houses were erected with symmetrical façades, classical columns and round arches. Wealthy individuals directed their funds towards displays of taste and refinement in country houses, with portraits and collections of books and artwork, rather than looking to the church to guarantee them safe passage through purgatory as their medieval ancestors had done. As a result, few new churches were built after the 1530s and the Gothic style of building had all but died out by the mid 17th century.

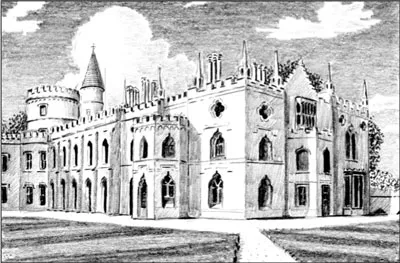

FIG 1.4: Strawberry Hill, Twickenham, London: Horace Walpole’s Gothick fantasy based upon medieval buildings but arranged and adapted to form a unique style.

Gothick

The revival began in the mid 18th century when the garden designer Batty Langley published Ancient Architecture Restored and Improved in 1742 (renamed Gothic Architecture, improved by Rules and Proportions in 1747) in which he adapted Gothic forms by applying Classical rules. This resulted in a range of whimsical follies, with only a loose similarity to medieval buildings, appearing in the landscaped gardens of the rich. A more ambitious scheme was devised by Horace Walpole, the fourth son of Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole who, from the early 1750s through to the late 1770s, transformed a small villa he had purchased in 1747 near the Thames at Twickenham into a Gothic fantasy. Strawberry Hill was the first major domestic building in this revival style, with Walpole’s Committee of Taste helping him to design and build the white-rendered structure embellished with battlements, pinnacles and pointed arches adapted from actual medieval structures; the result inspiring a generation of villas, cottages and gatehouses. However, this fanciful style using parts from large buildings and squashing and squeezing them into compact but distorted forms was not a serious attempt to understand the mechanics or motivation behind the originals on which they were based, hence this first phase which reached a peak in the Regency period is known as Gothick.

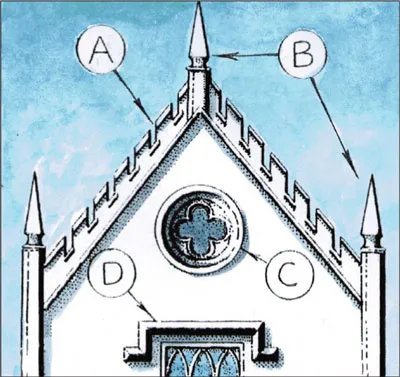

FIG 1.5: Late Georgian and Regency Gothick houses were distinguished by being covered in stucco (an external render) which was originally painted in beiges and greys to imitate fashionable stone but today are usually white. Other common features were battlements (A), pinnacles and finials (B), quatrefoils (C), and hood moulds above openings (D). Windows often had pointed arches or ‘Y’-shaped glazing bars.

The Gothic Revival

Attitudes towards medieval architecture began to change from the early 19th century. War with Napoleon had slowed the flow of young aristocrats taking Grand Tours of the classical wonders of Europe while a growing appreciation of the sublime and picturesque inspired many to look at our own historic buildings. Some of the most patriotic created new castles and abbeys in the medieval style and, a little later, Tudor-and Elizabethan-style mansions. At the end of hostilities, artefacts from the Middle Ages flooded the market and collectors began studying manuscripts, illustrations and carvings in more detail, none more so than Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, the son of a French draughtsman, who began to unravel the principles behind Gothic buildings and set in place practical rules and moral codes which would guide the next generation of architects and artists. His incredible output in such a short life (he died aged 40 in 1852) included designs for the clock tower housing Big Ben in London and the interiors of the Houses of Parliament, churches, country houses, and volumes of drawings and books. These included Contrasts (1836) in which he compared contemporary buildings with their medieval equivalents in such a way as to promote his belief that the latter were morally and socially superior.

Pugin was working in a period when the Church of England finally woke up to the changes taking place in society and the rapid expansion of urban areas which had left a large proportion of the population beyond its reach. At the same time the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 meant that Catholics too could now worship in public, hence there began a massive church building programme which would last through most of the 19th century (Pugin himself converted to Catholicism in 1834). These buildings, however, would not be the cavernous, box-like chapels with shallow roofs, round-arched windows and symmetrical fronts which had been the standard form for the past century or two. Now, after the Oxford Movement had encouraged the introduction of many medieval practices into the Anglican church, Pugin and the Cambridge Campden Society (later renamed the Ecclesiological Society) promoted Gothic as the most appropriate style for these new churches, more precisely that of the 14th century. They were asymmetrical with towers and spires, ornaments restricted to structural elements, and the division between the nave and chancel now clearly displayed on the exterior, with the walls at first in stone but, by the 1850s, in red brick as it became more acceptable (especially after the repeal of the brick tax in 1850 made it cheaper).

Alongside these were erected new vicarages which reflected the style of the church, with a steep-pitched roof, prominent gables and chimneys, and pointed-arched windows or doors. These buildings looked more like a compact, asymmetrical country house, with a tall window breaking through the storeys reflecting that of a medieval hall. At a time when most houses were Classical, Italianate or Tudor in inspiration, these ecclesiastical homes were something of a revelation.

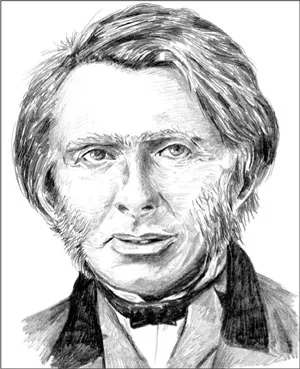

FIG 1.6: John Ruskin (1819–1900): This most inspirational of art critics conveyed his highly moralistic Christian beliefs, love of nature and admiration of medieval Gothic buildings and the craftsmen who built them through a series of influential books, the most notable being The Stones ...