![]()

SECTION I

CHURCHES

THROUGH

THE AGES

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Saxon and Norman

Churches

AD 600–1200

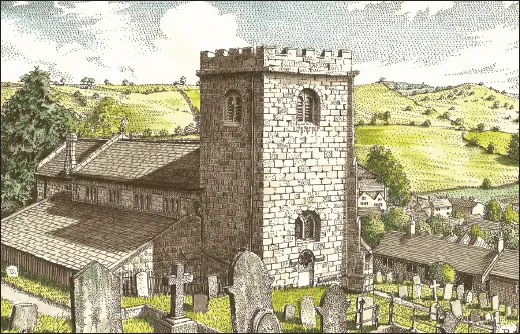

FIG 1.1 BRASSINGTON, DERBYS: This church set on the edge of the Peak District was built in the 12th century, yet as with most examples from this period the evidence is buried under later changes. The stocky, plain tower with its distinctive round-arch bell openings is the only part in this picture which is instantly recognizable as Norman.

In the closing decades of the 6th century Britain found itself under invasion on two fronts. Not from further bands of pagan Saxons who over the previous hundred years had pushed the existing Romano-British and their culture into the West, but from Christian missionaries seeking to convert the population (in effect, to reintroduce a religion which had established itself in the last century of Roman rule). St Columba, who had travelled over from Ireland and founded a monastery on Iona in AD 563, and his followers influenced the North while Augustine, sent by the Pope, had landed in Kent in AD 597 and established a base in Canterbury (London was resolutely pagan!). The inevitable differences between the two as they spread across the country was ironed out at the Synod of Whitby in AD 664 and, over the following century, a system of a regional central minster dispatching preachers to outlying field churches or open air sites was created.

Viking raids and later invasion during the 9th century ruined monastic life and crippled the Church until Alfred and his successors forced them back and established England as a single state by the mid 10th century. Under Edgar (AD 944–975) church building flourished, now not just minsters but new, smaller estate buildings, as lesser nobles sought to gain higher status by erecting a church next to their manor house, a fashion which continued over the next 200 years. At the same time the payment of tithes to support the priests was put in law and a parish from which they were to be paid was established, many following the boundary of these local estates. The majority of our medieval parish churches are likely to have been founded this way by Saxon nobles and after the Conquest by Norman barons until the late 12th century when the old minster system was virtually obsolete.

Saxon Churches

Part of the success of the early missionaries is likely to have been due to their adoption of existing pagan religious sites, and many early churches were built alongside holy wells, ancient stones, burial mounds and Roman remains. They were usually simple rectangular structures, mostly built from timber and have long since gone (an exception is in Fig 1.17); those which survive are the ones built in stone. These relied upon the bulk of their walls for stability and the thickness was exposed at the windows which were typically small with many splayed on both sides so the shutter or material used to close them off was in the centre (glass was rare).

FIG 1.2 STOW, LINCS: This outstanding example of a large Late Saxon cruciform church dwarfs the tiny village around it. Its size and dominant position are clues that it was once an important minster. These early principal churches were mainly established in the 7th and 8th centuries near important centres of the day and acted as a missionary base from which priests or monks could go out and preach to other communities within a territory. The creation of parishes from the 10th century broke down this system. Their presence is also still recorded in place-names like Kidderminster, or where they became a cathedral as at York Minster.

The main body had a distinctive tall, narrow form, most with a smaller chancel built onto the east end and a few larger churches having transepts to the sides and a tower. Where the wall had to be supported above a window, doorway or the opening between the nave and chancel, a simple round arch was used, typically narrow with tall sides. The roof above would have been steeply pitched and most likely thatched.

FIG 1.3: Churches built near ruined Roman towns or villas often raided their masonry (see Fig 1.18) for thin red bricks, then incorporated them into walls and arches as in this example at Brixworth (top). A distinctive feature of Late Saxon and Early Norman churches was the laying of stone in a herringbone pattern as in this example from Marton, Lincs (bottom).

Most of what you see today from this period will be fragmentary. Of the couple of hundred churches that display their Saxon origin, this is usually only indicated by the distinctive narrow profile of a nave or a single round headed window.

FIG 1.4: A distinctive feature of Saxon churches was long and short work, where narrow stones were alternately placed vertically and then horizontally on the corners (quoins).

FIG 1.5: Windows were usually small with a single and occasionally a twin opening (often with an elongated barrel shaped baluster in the centre). Most had a round head, smaller ones crudely carved out of a single block (top), larger examples with the arch formed out of carved segments (centre). A unique form on some Saxon churches was the triangular head (bottom).

FIG 1.6: Doorways (and the chancel arch inside) were typically simple and narrow with a lack of confidence in the size of the round arch limiting their width. They have a large impost stone from where the arch springs and occasionally attached columns.

FIG 1.7: Columns and the capitals on top of them are only found in a few Saxon churches. They are simple in form, often with decorative carving (the Saxons were in some ways more skilled craftsmen than the later Normans).

Norman Churches

William the Conqueror’s bloody arrival on these shores was followed by a large-scale building of castles and cathedrals; imposing structures designed to leave the rebellious Saxon population in awe. Apart from these there were few major churches built, it was the continuing pattern of local lords erecting new places of worship alongside their manorial homes which dominates this period. Parish churches found next to earthworks of motte and bailey castles are a common remnant of this link. However, a drive for a more pious Church during the 12th century encouraged these secular owners of churches to surrender the rights they had to appoint priests and collect revenue for services (part of the motivation for many to build the church in the first place) and place them into the hands of bishops and monasteries.

These early Norman churches have much in common at first glance with the simple, narrow Saxon structures except that an apse, a semi-circular extension to the chancel, was a popular import at this time from France. Towers were not common in most areas although on major build...