eBook - ePub

Abbeys Monasteries and Priories Explained

Britain's Living History

Trevor Yorke

This is a test

Share book

- 129 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Abbeys Monasteries and Priories Explained

Britain's Living History

Trevor Yorke

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Abbeys of the middle ages remain some of the most wonderful of religious buildings. They were built with a firm sense of devotion, and with no expense spared, by communities which had a faith based upon venerable respect for the power and authority of the Church. The grace and majesty of their construction, and the beautiful rural settings of so many, make them a perfect destination for visitors throughout the year. Trevor Yorke, using diagrams, photographs and illustrations, explains the history of these buildings and describes how they were used in the centuries prior to the great Dissolution by Henry VIII in 1536, which left most of them in ruins.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Abbeys Monasteries and Priories Explained an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Abbeys Monasteries and Priories Explained by Trevor Yorke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Religious Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Religious ArchitectureSECTION

I

THE HISTORY

OF

ABBEYS

CHAPTER 1

Definitions and Origins

Definitions

Before looking into the history and features of abbeys, it is worth differentiating between the myriad of names that we associate with the subject. A religious house is a community of monks or nuns living together, more commonly called a convent when applied to the latter (but the term can be used for either sex). In most cases, therefore, a monastery is a religious house comprising monks, while a nunnery is a convent of nuns (it seems, though, that the word monastery is often applied to all types of religious houses and to both the community of monks and the buildings in which they live).

The important words for the purposes of this book are abbey, which is a monastery or nunnery of large size or high status, and priory, which is a smaller house, often subordinate to an abbey, although some grew in size and status to become just as important. A friary is the home of friars, a later group who relied upon begging for their income and spent much of their time preaching in the outside world, as opposed to monks and nuns who resided almost permanently within their abbey or priory. Between these are canons, who are divided into two types: regular and secular. The former (from the word regula, meaning rule) lived like monks by strict monastic rules within their own abbey or priory, but unlike them also preached outside. Secular canons were not connected with monasteries and were usually associated with other religious establishments such as cathedrals and colleges.

The principal member of the community was the abbot or abbess in an abbey and the prior or prioress in a priory, the latter often acting as deputies to their superiors at the abbey. Below these on the monastic social ladder were the obedientiaries, who were monks put in charge of the various departments of a monastery and typically named after them, like the cellarer, kitchener and infirmarer.

Monasticism is divided into two forms: eremitic, where monks live an isolated existence as hermits, and coenobitic (derived from the Greek for ‘common life’), where the monks spend at least part of their time within a community. Although this book will focus on the latter form and the spectacular abbeys these religious groups built in Britain, eremitical monasticism was not only ever present here, but also appeared alongside the coenobitic form when monasticism first took shape.

The Origins

There have been men and women who have isolated themselves from the outside world to seek a closer union with God since the earliest days of Christianity. A life of denying themselves indulgences (known as ‘asceticism’) and spending their days in solitary prayer began to appeal to a growing number of people more than 1,700 years ago. Perhaps inspired by Jesus and his forty days and forty nights spent in the desert, they sought a similar environment, the area along the River Nile, to the north-east of the Sahara (modern day Egypt) proving particularly attractive.

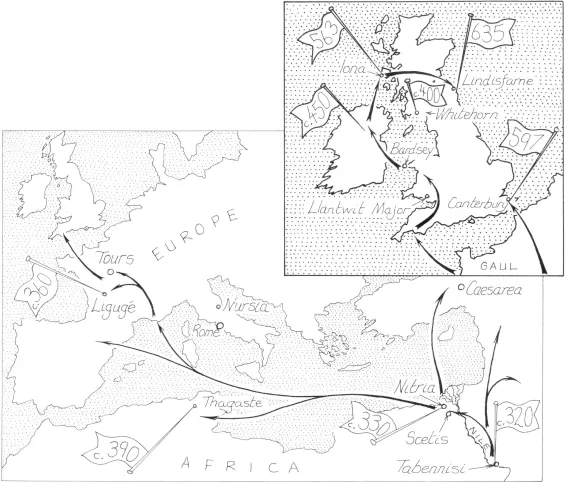

FIG 1.1: A map of Europe and close up of the British Isles showing the probable route by which monastic ideas spread from Egypt across modern day France and into Britain. This did not happen as one fluid movement but via individuals establishing religious communities at various locations and dates. The flags give approximate dates for the foundations of monasteries.

Paul of Thebes was possibly the first of these pioneers, who were later referred to as the ‘Desert Fathers’, becoming a hermit in his youth and living a solitary life surrounded by the shifting sands until his death around AD 341. St Antony, known as the Father of Monasticism, lived around the same time, spending his final forty years in a hermitage on Mount Kolzim, near the northern tip of the Red Sea. Perhaps more relevant to our story is Pachomius, an ex-soldier who used his military background to form many solitary Christians into disciplined groups of men, with his first community established at Tabennisi in around AD 320.

These early religious houses spread like wildfire, appearing on the outskirts of Egyptian towns and villages and in various isolated locations during the 4th century. They were probably unplanned settlements with wells, an area for cultivation and simple structures containing a single room or cell for the monks, all within a walled enclosure. Mealtimes and services may have been the only occasions on which the members of the community had contact, and it is recorded that even here they did their utmost to ignore one another and preserve their ascetic lifestyle.

This self denial and discipline reached unwelcome extremes as these religious loners sought to out perform each other with increasingly severe punishments. One character, Macarius, chastised himself for killing a solitary mosquito by spending six months naked next to an insect-infested marsh, emerging unrecognisable as his body was swollen and scarred by bites. He also went without cooked food for seven years for no better reason than that he had heard another group of monks did so for the period of Lent. Eventually, this competitiveness, which was itself a sin, was replaced with more reasonable behaviour.

Much of Europe in the 4th century still formed part of the Roman Empire and, with its acceptance of Christianity under the Emperor Constantine from AD 305, the religion was able to spread freely. The Empire was built around trade and there was constant movement of goods and people between countries, making it easy for monastic ideas from Egypt to be transported abroad. Hilary of Poitiers, for instance, had come into contact with monasticism while in exile in the East and on returning to Gaul (modern day France) had along with St Martin (who had already established a monastery in Milan) set up a community at Ligugé. They may have used an existing Roman villa site, a pattern which repeated itself across the old Empire. This illustrates a theme running throughout the history of monasteries – that they were founded by wealthy individuals of high status on estates within their gift.

The First British Monasteries

It is still unclear when the first monasteries were established on the British mainland, although it is unlikely that it was before the departure of the Roman legions in AD 410, which is commonly seen as marking the end of the Empire in Britain. Roman life actually carried on for some time as the remaining Romano British population of some four to five million still dominated the country, but, with the breakdown in the market system, the large cities and towns that it had supported could no longer be maintained. Although already present in Roman Britain, Germanic groups (including Saxons and Angles) began to increase in number, so that by the 6th century the Christian Romano British culture found itself confined to western Britain.

Although it is recorded that monastic sites were founded in the 5th and early 6th century (e.g. Llantwit Major and Bardsey Island in Wales) no site from this Dark Age period has been positively identified. It is most likely that monastic ideas spread from Gaul through the Celtic regions in the west and over to Ireland, as is famously recounted in the story of St Patrick who established a house in Armagh sometime around AD 450. Our story, though, will really begin in the middle and late 6th century, when Christianity returned to the British mainland not just from one source but two.

CHAPTER 2

Celtic and Saxon Monasteries

500-1066

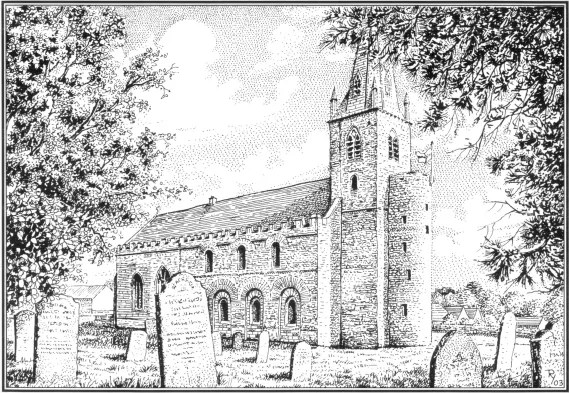

FIG 2.1: BRIXWORTH CHURCH, NORTHAMPTONSHIRE: A rare surviving church, in part dating from the 8th century. Ignore the later tower and semicircular stair turret, it is the main body of the building that was part of an early monastery. The bottom row of round arched windows were originally openings into what are believed to have been individual chapels that stood up against the sides of the wall.

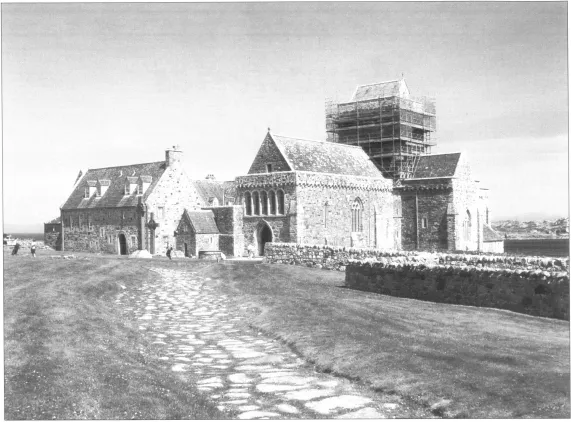

FIG 2.2: IONA ABBEY, OFF THE ISLE OF MULL: The structure in the picture is a medieval monastery built on the site of the religious house founded by St Columba in AD 563. The tiny pointed-roof building to the left of the west end of the church (the five windows in a row) is known as St Columba’s Shrine and was a chapel, which may date from the 9th century. In front of it are a number of stone crosses, some dating from the 8th century, which probably marked the route for pilgrims to the shrine.

Brief History

Sometime during AD 563, there came to a small island off the west coast of Mull, an Irish noble who, it is said, was banished by holy men as punishment for slaughtering too many in battle (although it was more likely to have been because he had become too powerful). The man was Columba (later Saint) and his landing place was lona, where he established a monastery along the lines of a new generation of religious houses he had already founded in Ireland. It was to this monastery that King Oswald of Northumbria, the most dominant power in England at the time, turned for his bishop in AD 635. St Aidan and a group of monks were despatched and settled on Lindisfarne (Holy Island), establishing a community second only to lona. This Celtic Christianity was spread by others down into the Midlands and the South while, in return,...