![]()

CHAPTER 2

Roman and Medieval Arched Bridges

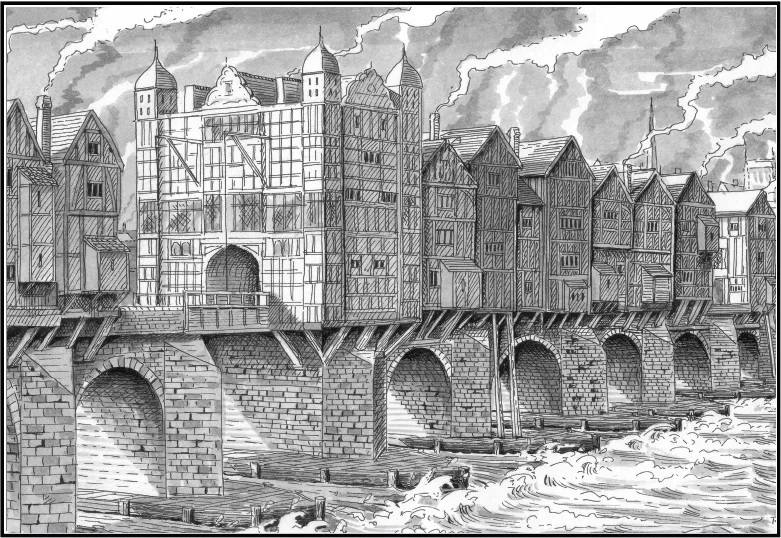

FIG. 2.1: LONDON BRIDGE: An impression of how the first stone London Bridge may have appeared in the 16th century. It had been designed by a priest, Peter of Colechurch, who died shortly before its completion in 1209 and was buried in the crypt of the chapel which stood upon it. His structure survived for more than 600 years, but when it was demolished in the 1830s his bones were uncovered and are believed to have been discarded into the Thames by workmen.

‘London Bridge is falling down, falling down, falling down.’ The well-known nursery rhyme of which this is the opening line is almost certainly of ancient origin and probably refers to an earlier bridge than the first stone structure in the picture above. The Romans had built a timber bridge across the Thames in this area, and this or a later one was damaged by fire and was replaced by a similar structure in 1169. It is not clear why, but less than ten years later the new stone bridge was begun. It was 900 ft long, with huge stone piers sunk into the tidal river. These were almost as wide as the arches or spans backing the river upstream of it, and had the effect of slowing the flow enough for the water to freeze over in winter and at the same time creating such a strong current below that the river bed was scoured out to a depth ideal for shipping in what it still known as the Pool of London.

What must have appeared most striking at the time was not just the scale of the project – it took over 30 years to build – but the imposing row of nineteen stone arches. Previous struc tures had used timber beams, and stone-arched bridges were rare at the time and unknown here on this scale, yet the bridge’s superior load-bearing capacity meant it could support the community of houses and shops which grew up on it and came to characterize it.

London Bridge had been rebuilt to maintain the capital’s position as a trading centre, and, although many medieval structures were constructed with convenience in mind, most were usually concerned with keeping traffic moving to market. Towns could grow or fail depending on whether they had a permanent crossing point.

After the Romans landed in AD 43 the first roads and major bridges were built by the army to ensure that legions could move swiftly to any corner of the empire’s new acquisition in order to quell uprisings. Their main use, once order had been established, was trade – the movement of grain, goods, and materials to local markets and foreign ports – which had been one of the main reasons for the invasion in the first place. It was the loss of this national market network when the last legions left these shores in AD 410 rather than the influx of Germanic tribes which in part distinguished the supposed Dark Ages from the preceding times. Most of the Roman roads and bridges fell into disrepair because the country fragmented into smaller tribal groups, so that long-distance trading routes were used less. In some cases new centres were established away from the existing roads. Some bridges were maintained, and new ones were constructed but these were timber structures with horizontal beams supported on vertical piles or stone piers (see Chapter 6).

It was not until a more unified kingdom emerged in the 10th century, and then an increase in trading and the founding of new markets in the 12th and 13th centuries, that new more permanent bridges were deemed necessary. Some were built to replace earlier timber structures; others were constructed as part of a new road or town, with the intention of diverting business away from a neighbouring market. Most goods were transported by horse or mule, and so medieval bridges were generally only wide enough to let a single vehicle pass. (Nearly all, though, have subsequently been widened.)

FIG. 2.2: ST IVES BRIDGE, CAMBS: This early 15th-century bridge with its original chapel (see Fig. 2.21) replaced an earlier structure which was built around 1100. It played an important part in making what was previously a small village and priory into an important medieval town and was possibly constructed and financed by the abbot of the mother house.

There was no controlling transport body in the medieval period and bridges were built by a variety of individuals or groups. Many were paid for by the church, monastic orders, town or city guilds, burgesses, or wealthy lords, while some were funded collectively by the local nobility who would benefit from it. The Crown, however, was rarely involved in bridge building. Deciding who was responsible for maintenance once it was completed was another matter. If the original builder could not be established, then responsibility fell upon the local parish and, if the money could not be raised from wealthy individuals, groups, or charities, then a grant of pontage would enable tolls to be charged for any necessary work. Many had chapels upon or near the structure, where mass could be chanted for the deceased, or indulgences granted by the church for remission of sin, in return for financial contributions towards the bridge’s upkeep. In other cases rent from land and buildings was bequeathed for this purpose.

The stone-arched bridges of this period varied in size from small structures for packhorse traffic to large, multi-arched examples across major rivers. However, there were only two main types of arch used: semi-circular and pointed.

SEMI-CIRCULAR OR ROMAN ARCHES

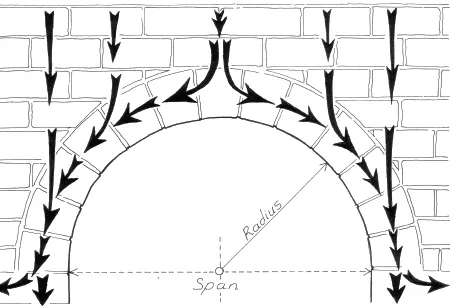

Although possibly first devised by the Sumerians as long ago as 4000 BC, it was the Romans who first developed and widely used a semi-circular arch, although in bridges in this country it was rare. It is in medieval structures that the earliest examples will be found, comprising wedge-shaped stones (voussoirs) arranged in a half-circle with the narrow ends on the underside. (Alternatively, regular shaped stones could be used with mortar filling the gaps.) The downward pressure from their own weight and that of any load built on top forces the stones tightly together, in effect transferring the force from above down the sides and onto the point from which it springs. A small force is transferred to the sides, however, and so the designer also has to bear this in mind (see Fig 2.3). This simple and ingenious design enabled the Romans to bridge large gaps with small sized blocks and to create more lasting and stronger structures. The arch is so durable that it can survive movement in its foundations or abutments to such a degree that one, two, or even three cracks or hinges in its line will not lead to collapse; only when a fourth appears will it fail.

FIG. 2.3: A diagram showing a semi-circular arch. The arrows show how the weight of the structure above and the load it carries are transferred out towards the piers and sides of the bridge.

FIG. 2.4: An example of a semi-circular arch with a single ring of voussoirs; the chamfered edge on the lower side was a feature of later medieval bridges.

A problem with a semi-circular arch, however, is that it does not achieve its strength until the central voussoir (the keystone) is put in place. This means that the arch needs su...