![]()

| MEDIEVAL SIEGE WARFARE Kings, Knights and Castles |

In the medieval world kingdoms were won, monarchs toppled and nobles gained new lands through the successful attack upon, or defence of, a castle. Those who tried to capture the fortification could launch a surprise attack or besiege it for weeks and sometimes even months, often resorting to extraordinary actions in order to break through the defences. They used siege engines to pound the walls, archers to pick men off the tops of the walls, and sent incendiary devices over the battlements to set fire to the buildings within. Tunnels were dug under the walls; sappers sent up to pick at the masonry in order to create a breach; siege towers and ladders were used for an assault over the top. Some attackers even fired contaminated corpses into the castle to spread disease, or they had prisoners executed in front of horrified defenders to try and induce surrender.

Medieval commanders were not afraid to employ deception and intrigue with devious tricks used to try and enter the castle gates or have spies planted inside to find out vital information. If a direct attack failed then the defenders, cut off from gaining fresh supplies, could eventually have to surrender through starvation or lack of water. Medieval siege warfare was not a rapid process and much of a medieval king’s, baron’s and knight’s time and money was spent attacking an enemy’s castles or defending their own.

Those trapped within did not just sit down and wait for the inevitable end. Sieges were two-way battles and the defenders were just as likely to go onto the offensive. They too had siege engines which could take out enemy weapons and personnel. They had giant crossbows which could pierce armour and shields and they used fire to destroy the attackers’ machinery. Most castles had a discreet rear exit so soldiers could slip out at night and raid the enemy camp, take hostages, or get a message out to send for a relieving force. Defenders upon the battlements had the advantage of height so heavy objects and red hot substances could be dropped around the walls or gates while archers had a good line of sight to shoot unwary attackers below. King Richard I, idealised as one of our great monarchs despite spending only a few months of his ten-year reign in this country, was inspecting progress on the siege of a small French castle when he was shot by a crossbow bolt fired from the battlements by a boy and he died a few weeks later from the wound. So although attackers would seem to have the upper hand with their wide range of weapons and tactics, in most cases defenders still had a few countermeasures available, and in some cases they could even turn the situation to their advantage. From the Norman invasion in 1066 through to the early 14th century castles were the centre point of military activity in Britain and through them the fate of a king, prince or noble could be decided.

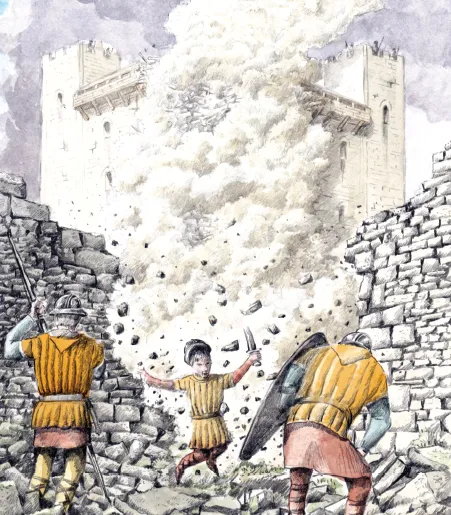

FIG 1.1: The moment in late November 1215 when, after nearly two months of besieging Rochester Castle, Kent, military miners working for King John finally brought down the corner of the mighty stone keep. This unpopular monarch had broken his promises made in the Magna Carta, so rebel barons rose up against him, capturing a number of key castles including Rochester. The king’s forces had attacked the defences with crossbows and missiles, and bombarded its walls with siege engines. But, it was only when they undermined its fortifications by digging tunnels beneath the structure that they finally broke through. Despite this, the defenders held on within one half of the keep for a further few days before surrendering when their supplies ran out.

Why were castles so important?

Why did medieval commanders go to great lengths to capture or disable castles? Part of the reason was that most medieval kings were wary about major battles, which they saw as unpredictable and dangerous events in which an army could be wiped out in a matter of hours. A war could be fought with the forces split across a number of sieges so that if one failed all was not lost. Many early castles were positioned to guard a key route or a river crossing so an invading army would have to pass by thus making them vulnerable to attack. Some castle ruins can be found today at the head of a lonely valley or by a seemingly minor bridge because when they were founded these were either important routes or the only crossing in the area. If an army tried to bypass these strategically placed fortifications then it could add days onto a march, which would give the enemy time to prepare. It could also cause problems because the garrison in the castle could ride out and disrupt their supply chain. In 1216, when Prince Louis of France invaded Southern England and marched into London, he neglected to first disable the castles which stood between his army and the south coast where his supplies were landed. As a result, the garrison at Dover Castle constantly disrupted his supply chain taking up so much time and resources that his invasion faltered and he was ultimately paid off to refute his claim to be King of England. Castles were also important because they were not just a military establishment but also the home of a king or noble. Unlike earlier Roman forts which were purely military bases, or Saxon burhs which were fortified towns, castles were designed to accommodate both an armed garrison and the wealthy owner and his household. Anyone trying to take over a territory could not claim to be the new incumbent until the previous one had been removed from his castle.

FIG 1.2: The castle was built upon a high point with a towering form not just to be impenetrable but also to overawe the conquered population. Its formidable defences, battlements and huge towers sent a message to them that the owner and his troops were an immovable and invincible force which was there for the long term. King Edward I had this in mind when he built Caernarfon Castle, pictured here, which became the centre of English rule over the Principality of Wales after his victorious campaign in the 1280s.

Who lived in the castle?

The castle was the home of a king, lord or knight, although sometimes a lady might be in control when her husband was absent or had died. Monarchs had their own royal castles which they would constantly travel between. Their number fluctuated as some were granted to feudal vassals as a reward while others were confiscated in punishment. The majority of castles however were in the hands of lords and knights who were responsible for keeping order over their fiefdom or manor and providing military service when called upon. In the absence of the owner, castles were run by the castellan, castelain or constable, a role which could include responsibility for the garrison of soldiers as well as the daily running of the fortification. As a king and his nobles would have a number of castles and could only be at one place at any time it was often the castelain who defended the building and organised the garrison when it was besieged. The castle was a busy place even in times of peace with soldiers training, blacksmiths making and repairing weapons and armour, and carpenters and masons building. The outer bailey or ward not only contained workshops and storage for supplies but also the men’s accommodation and stables for the horses.

How to conduct a siege

As the fate of a kingdom could centre upon gaining control of castles, the attack and defence of them had to be thoroughly planned. The first approach in most situations was to try and avoid a siege by allowing the garrison to surrender. This was regarded as a chivalric move (the chivalric code was an unwritten code of chivalrous social behavior between knights and nobles) in part to protect the unnecessary loss of nobles and knights, but it also made sense because a siege would be an expensive process for both sides and could result in damage to the castle which would then be costly for the victor to repair. Sometimes the reputation of a feared commander or a huge army might force the garrison to throw open the gates of a castle before they had even arrived. In other cases, diplomacy or bribery could be used so that a compromise was reached by which the castle would be spared as long as it did not then threaten the attacker’s progress. As a monarch or lord usually had a number of castles each one was left in the hands of his castelain or garrison commander. If they were unclear on their instructions or were unable to communicate with their master, they might be more susceptible to surrender. In other cases, if the owner of the castles had been captured then he could be forced to send orders for them to open the gates.

FIG 1.3: Castles were generally located in a strategic military position or in a location where they could control the local population and trade. They were very rarely positioned on top of the highest hill but were sited lower down in a dominant position close to river crossings, the head of a valley or in a town or city. Many were located on a natural promontory or mound while others were built on relatively flat land so that artificial mottes, ditches and moats had to be created as defensive measures. It was also common for a new town to be established or to develop close to the castle as here at Dunster Castle, Somerset. Although this would seem to be an advantage for the inhabitants as they could seek refuge if an army approached, they were often kicked out of the castle if supplies got low and could be massacred by attackers frustrated that they could not break though the walls.

If a fight was inevitable then both sides usually had a little time to prepare. Some commanders had access to the works of the Roman military author Vegetius and were influenced by his belief in extensive training, thorough preparation, and waiting to make a decisive move when victory was virtually guaranteed. Those defending the castle would have to make sure they had good supplies of food and a reliable source of water, as well as the materials to enhance their defences and a stock of weapons plus the carpenters and blacksmiths to make and repair them. Those besieging would need the same and as the area around the castle might have been burned or cleared of such supplies before their arrival they might have to wait some time before they could commence their attack. Timing was also an issue for a military planner. Late spring and early summer was the best time to attack when the weather was favourable. The stock of food in the castle would be low and water was liable to run out. For a besieger, winter was usually avoided due to the wet and cold while many of those serving would frequently go back to their homes in order to sow seeds early in the year. The same difficulty applied at harvest time towards the end of the year. The commander of the garrison was penned into his castle, but even he had to consider the soldiers and knights who were serving as part of their feudal duties. This commitment to help with the defence, known as castle guard, only lasted for a set period, typically around two to three months a year, so they were within their rights to walk out if a siege extended beyond this time. As this could be inconvenient for both parties it became common for them to give their lord a payment rather than serve, money which could be spent on better trained and dedicated mercenaries who would be expected to fight to the end.

The Roman Influence

Many medieval kings often saw themselves as natural successors to the Romans. Medieval clerics translated surviving texts from the ancient Roman authors such as Vitruvius and Vegetius, which would have given them access to some of the empire’s military tactics and the design of both their defensive structures and siege engines. As the Roman Empire had survived around Constantinople, medieval kings and knights may also have been influenced by the forts and weapons they came across while on the crusades. In addition, there were the remains which the Romans had left behind in this country. They had built mighty stone and brick walls for their forts and town defences; most spectacularly along much of Hadrian’s Wall. They had towers and gatehouses which were designed to resist an attack and above all, a network of well-built roads which could give their forces a direct route so they could respond quickly to any incident. Many of the earliest castles were established on the site of a Roman fort or were built reusing the material from their defensive walls.

FIG 1.4: Castles were multifunctional centres for a town or territory. They were a military base from which armed knights and soldiers could venture out and suppress rebellion or raid neighbouring land. Castles were the home of a king or noble so could have a grand hall and fine accommodation. There would also be room for the numerous household servants and carts full of belongings that the owner travelled with between visits to their properties. They would usually only stay a matter of weeks at each one.

The high walls and towers were essential as look-out posts to warn of approaching armies and the rooms underground were vital to store supplies in case of a siege or the arrival of the owner. Castles also became the administrative centre of a territory, from where a lord could carry out his feudal role, soldiers could patrol the area, courts could be held and prisoners thrown in jail. Many castles have survived into the modern age because they were convenient courtrooms and prisons long after their military value had faded. Norwich Castle, pictured here, still has the old prison buildings which were added to the rear of this mighty Norman keep.

Once the castle had been surrounded the attackers would often go on the rampage, raiding the surrounding towns and villages for loot and burning the countryside to deprive the castle of supplies if this had not already been done by the defenders. Initially men would have been kept occupied erecting siege engines, digging ditches, raising banks and in some cases building temporary castles so the besiegers would be safe from a surprise attack. If a siege dragged on then keeping the morale up of those inside and outside the castle could soon become a problem. The constant pounding of stone balls smashing into walls or the dead bodies of colleagues being catapulted into the castle could take their toll on the mental state of those trapped inside. The attackers could equally become demoralised if they saw that their attempts to break through were constantly failing. A deal which was sometimes struck allowed the castelain or commander to send out a message to his master for instruction on whether to continue the defence of the castle on the promise that if he did not receive a reply within an agreed time he would surrender. Sometimes a belligerent commander might persist with a siege despite the castle being impenetrable or the defenders might refuse all offers in the belief that they might be saved by a relieving force be...