![]()

| VICTORIAN

RAILWAY STATIONS |

History and Style

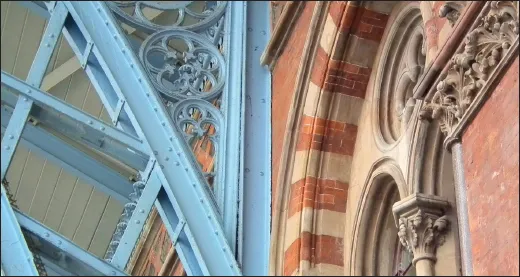

St Pancras Station, London: George Gilbert Scott’s Midland Hotel is a Gothic masterpiece which reflects the ambitions and confidence of Victorian railway companies. It opened in 1873 and still offers luxury accommodation.

Victorian stations stand today as a tangible monument to the railway age. Their impressive structures and colourful historic styles reflect not just the admirable quality of buildings from this period, but also the ambition and confidence of the men who designed and built this exciting new transport system. Just as the railways were at the cutting edge of 19th century technology, so the station buildings were built in the latest styles with their glorious façades designed by the era’s leading architects.

Railway stations were one of the few places where society would intermingle. Although early stations were geared towards the well off, it was not long before the middle and working classes were crowding upon the same platforms. In most communities the railway station was the primary link to the outside world, the point where distant friends and family were received, the latest news and fashions discovered and local produce dispatched to far off cities. Victorian industry and society revolved around the railway station; towns and cities were drawn towards their location with new housing, warehousing and factories developing around them. The buildings which stand today reflect this importance, and the demands, desires and expectations of the railway companies and their passengers.

Darlington, County Durham: Station built in fields on the edge of what was a small market town. In 1887, when the building was rebuilt with its impressive tower, the town had begun to spread around the site and today it seems part of the urban area.

In the early days of the railways, one reason why the railway companies felt the need to build such magnificent buildings was to reassure a nervous public. These thundering iron machines spitting sparks and billowing smoke, hurtled along at speeds faster than anyone had ever travelled before. They invoked wonder and fear. Many people believed the trains were monstrous, dangerous creations that would blacken the landscape and terrify livestock. By building such permanent and impressive stations in major cities and towns, the railwaymen sought to dispel these fears.

There was little regulation or centralized planning from government with hundreds of companies competing with each other for the same traffic. As a result it was only where one company dominated an area, or companies worked together, that there was a single main station serving a location. In most large towns and cities there were numerous stations, many built in an ever more imposing form or up-to-date style to attract potential customers away from their competitors.

Building stations

The size and grandeur of many Victorian stations implies that the railway age was a period of steady growth and guaranteed success. However, the development of the national rail network was a bumpy ride which ruined many investors and resulted in the building of lines that would never make a sustainable profit. The Railway Mania of the mid 1840s was a relatively short period of intense and at times crazed investment in a large number of schemes. This was followed by the inevitable fall, with periods of more cautious development. Those lines which received Parliamentary approval were built at an incredible rate. The speed by which railways were surveyed, land purchased and vast engineering projects carried out, in a period with limited communications and mechanical aids, was a wonder of the Victorian age.

Problems arose when new lines were driven by competition with another company, rather than by an increase in traffic. Even those lines which were a success and form part of today’s national network sometimes struggled to make an initial profit, after the capital outlay and expensive engineering works had been paid for. As a result, many important main lines initially had quite basic station buildings. Financial constraints also limited the choice of site in a town or city. Most companies chose to build their first termini on the cheaper land on the outskirts. This reduced opposition from the canals, stagecoaches and turnpike trusts that might lose out to railway competition, as well as the need to demolish existing buildings, or build bridges and tunnels to access urban centres. As smaller companies were bought out, or amalgamated to form larger enterprises, so they gained the financial power to rebuild these earlier stations. Many of the Victorian buildings we see today are either the second or even third to be built in that location, or mark the re-siting of a station from a less convenient location.

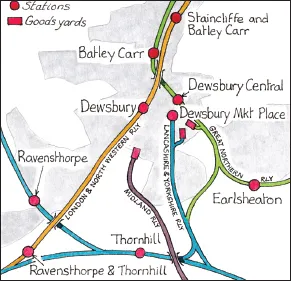

Dewsbury, West Yorkshire: Competition was rife between Victorian railway companies. Even a moderate-sized industrial town like Dewsbury, with a population of around 50,000 in 1910 when this map is dated, was served by four separate railway companies with nine stations within a two-mile square. The Midland had even planned another station near the town centre, but abandoned it when the Lancashire and Yorkshire let them use their lines. The section which had been built then served a large goods yard, in competition with two others in the town. There was a similar intensity of railway stations in many other towns across the country.

Salisbury, Wiltshire: Competition between Great Western and London and South Western for routes to the south west included a number of schemes for Salisbury. GWR arrived in 1856, with Brunel designing its simple terminus building (top). LSWR completed its new line from Basingstoke in 1859, and built a new station alongside (centre). This was in turn rebuilt at the turn of the 20th century (bottom). This has left us with three distinctly different railway station buildings on one site.

The railways drove the Victorian economy. This came in part from the rapid growth in transporting the produce of industry and agriculture to a world market. Around 40 million tons were carried in the early 1850s, which grew to 200 million tons by the 1870s. Coal was the most important commodity, accounting for around half of all goods moved. The economy was also boosted by the construction and running of the lines themselves. Around 60,000 men were involved in building new railways each year, while permanent employees numbered around 55,000 in 1850, and grew to around 600,000 just before the outbreak of the First World War.

Challenges facing the architect

Victorian railway stations were busy structures with a seemingly endless number of rooms which reflect many aspects of 19th century railway travel. The main entrance space would have been for the booking hall, with room for queuing passengers on one side and a busy office on the other. In the early days, there were usually only a few services each day with long journeys interrupted, so waiting and refreshment rooms were an important part of the station. Whole suites of these waiting rooms and facilities had to be provided to maintain the Victorian’s strict segregation of class and sex. The station was also the place where parcels, newspapers and telegrams were received and distributed; with room needed for sorting and dispatching them.

As there were so many railway companies, many main line stations also served as a headquarters, with offices and a board room on the upper floor of the building. It became standard practice for the station master to live on site, with his house either built as part of the main buildings, or as a separate home close by.

With the large scale of the operation, the numerous rôles the station had to fulfil and the fact that railway travel was completely new, the first Victorian stations were a challenge to the architects and engineers who designed them. Canals and turnpikes had never had to handle such numbers of passengers, while other large public buildings had a single rôle, with people moving around them in a more predictable manner. The railway station had to cope with sudden large numbers of people and goods, as well as provide space to sell tickets, keep passengers comfortable and refreshed, sort out paperwork, process parcels and mail, and house staff. The designers of the early stations were in effect inventing a building which would incorporate the functions of a hall, shop, office, house and inn, all in one coherent form which would be easily accessible by a public unfamiliar with this type of transport. Yet within twenty years, by the 1850s most of the development had taken place and the station buildings and platform arrangement had evolved into a form that we are familiar with today.

Development of Victorian architecture

The building of the railway stations occurred at the same time as some notable changes in architecture. These iconic buildings played a key part in the expression of new ideas and the promotion of the revivalist styles which dominated the Victorian period. The seemingly bewildering range of Gothic, Italianate, Classical and Renaissance details which we tend to focus upon gives the impression that architects simply copied the past. However, on closer inspection they were using elements from history to create new decorative forms, resulting in original buildings which are distinctly Victorian in style.

In the 18th century there was an academic approach to design; architects aimed for fine proportions strictly controlled by the Classical Orders. Georgian buildings are symmetrical, refined and elegant, but by the turn of the 19th century could seem plain and severe. Victorian architects began to reject these earlier restrictions and sought to explore a new Picturesque aesthetic, as if buildings had been taken from a painting of a romanticised past.

As the 19th century progressed, the focus shifted from flat, monotonous façades on to three-dimensional structures which could be viewed from many angles, each one creating a different appearance. Tricky angled and corner sites could be regarded with favour as they allowed the exploration of these new styles. Architects wrestled with asymmetrical arrangements of horizontal and vertical blocks to create pleasingly irregular structures. Surfaces were recessed and projected as architects orchestrated drama with areas of light and shade. The formerly horizontal skyline was now broken by tall chimneys, steep pitched roofs, spires and towers, in a fashion for emphasising the vertical which dominated much of the Victorian period. These new styles fulfilled a desire for a more lavish and luxurious appearance, with heavily decorated façades packed with carved details and different coloured materials.

St Pancras, London: Major Victorian railway stations can highlight the conflict between the architect and the engineer. Complex train sheds required mechanical engineering, while the main public face needed a more artistic approach. This contrast was heightened as 19th-century architects were taught to build upon the work of their predecessors and use historic styles as inspiration, while engineers were embracing new materials and methods of construction. At St Pancras, the leading ecclesiastic architect, George Gilbert Scott, designed the Midland Hotel with its colourful brickwork and Gothic details, while the railway company’s consultant engineer, William Henry Barlow, designed the train shed with its blue painted ironwork.

As the century progressed, there was a move towards honesty in design, believing that structural elements like columns and buttresses should only be incorporated for carrying the load, rather than mere decoration. Brick had been hidden under coats of stucco (plaster), which was then painted to give the appearance of stone. But by the 1850s, brick became fashionable again with decoration coming from bands of different coloured brick, rather than adding pointless architectural features. New materials like iron, terracotta and glass were celebrated and details which had been hidden in the past, like metal girders and guttering, were exposed and lavishly decorated.

Social division on stagecoaches was as simple as inside (cabin) or outside (on the roof). The word ‘class’ only came into common use due to the railways. Initially, there was first and second class, with th...