eBook - ePub

Chimneys, Gables and Gargoyles

A Guide to Britain's Rooftops

Trevor Yorke

This is a test

Share book

- 80 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Chimneys, Gables and Gargoyles

A Guide to Britain's Rooftops

Trevor Yorke

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The roof lines of our towns and cities are places seldom looked at from below. Yet they contain a world of architectural delights.

This easy-to-follow guide includes hundreds of photos and drawings of rooftops and their features from around the country and offers a fascinating glimpse into this overlooked aspect of Britain's architectural history.

Just above the shop fronts, offices, banks and public buildings lie elaborate chimneys, fancy ironwork, and terracotta mouldings of mythical beasts.

Our own homes too can have roofs decorated with intricate bargeboards, elegant parapets and patterned tiles. Each one has a specific role and their style can reveal much about the history of the building.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Chimneys, Gables and Gargoyles an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Chimneys, Gables and Gargoyles by Trevor Yorke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture General | THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING A ROOFStyles and Materials |

The roof is arguably the most important part of a building. Without it rain, snow and wind would penetrate inside making it uninhabitable and quickly ruining the structure beneath. At the same time it also keeps the heat in during winter and protects the interior from the effects of the sun. In traditional construction ‘a good hat and strong boots’, the roof and foundations, were regarded as the essential elements to ensure that a building would stand the test of time. As long as these were sound the walls beneath could simply be made of mud and straw and would last decades if not centuries. In addition to this protective role the roof is a prominent visual feature which can be used by the architect for dramatic effect. Its chosen form, the angle at which it is set and the colours and shapes of the covering material are a distinctive part of the architectural style of the building. Further interest is created by the decorative trimmings, dormer windows, towers, parapets, gables, gargoyles and chimneys which help create the lively skylines of Britain’s towns and cities.

How a roof works

In our wet climate it has long been appreciated that a roof is best formed with a slope, the angle or pitch at which it is set being determined by the covering’s efficiency in shedding rainwater. A porous material like thatch had to be set at a steep pitch so that the rain ran off or evaporated before it could soak through the layers of straw or reed. Large Welsh slates on the other hand had few gaps for water to get through and could be set at a shallow pitch. The effects of the wind also had to be accounted for as it would push down on the windward side and suck up the covering on the leeward. The pitch of the roof and the way in which the tiles or slates were fixed ensured a gale would not cause damage. In addition there was the dead weight of the roof structure and covering to consider, which could be greater in winter when snow was laying on top. A heavy covering like plain clay tiles or stone slates would require thicker or more tightly packed supporting timbers irrespective of the pitch of the roof.

FIG 1.1: Looking up at buildings can reveal architectural delights especially upon those from the 19th century. The 1891 Victoria Law Courts, Birmingham, pictured here, show how architects in this period used decorative towers, finials, chimneys, gables, cornice and dormers to create a lively roof line which can easily be seen from below.

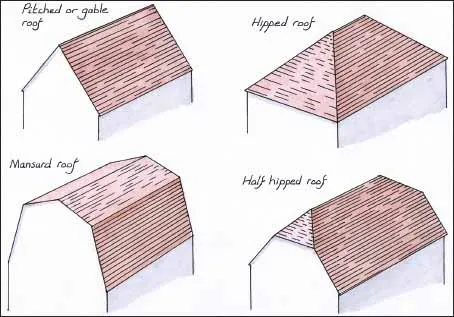

FIG 1.2: The most common forms of British roofs. Large buildings can be covered by a complex arrangement of slopes but still tend to be composed of these primary forms.

There was another problem which affected pitched roofs. Just as when you rest two playing cards at an angle against each other on a flat surface they are prone to slip and fall flat, so the sloping sides of a roof are always trying to spread out. The flatter the angle and heavier the roof the more they apply a horizontal thrust and try to push the tops of the walls outwards. Masons, carpenters and architects had to allow for this effect by adding exterior supports like buttresses or form trusses inside which tied the sloping sides of the roof together. This has placed restrictions upon the size and plan of buildings and their design has been in part shaped by the need to counter the effect of this spread.

FIG 1.3: Ely Cathedral, Cambs: Buttresses help counter the horizontal thrust from the pitched roof so the walls can be thinner and filled with glass. The flying buttresses pictured here are used in larger churches to span the side aisle with the decorative pinnacles on top acting as weights to add stability to the supports.

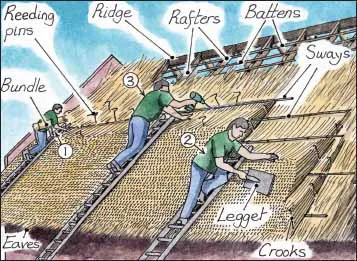

FIG 1.4: The straw or reeds are laid from the eaves upwards with the bundles spread out over the battens and temporarily held by reeding pins (1). The surface is then dressed with a legget, a wooden bat with a ridged surface, to form a smooth even surface (2). This is held by sways fixed into the rafters (3). A ridge piece is formed along the top and the eaves trimmed to complete the roof.

FIG 1.5: A limestone slate roof from the Cotswolds. The stepped slates projecting out are a traditional method of keeping rain away from the junction between the roof and the wall. Note the slates are larger along the eaves (bottom) and smaller at the ridge (top).

The style of roof

The form of the roof that you see when looking up at buildings has been shaped by changes in architectural fashion and the types of roof coverings used. The most common covering on medieval buildings was thatch (from the Old English thaec meaning roof covering), although straw, reeds and other vegetation fell from favour in many towns from an early date as it allowed fire to spread easily. In rural areas its use continued into the 19th century but by this time it was associated with poverty, covering the cottages and hovels of the poor. Today there are three types of materials used for thatching. Water reed has been traditionally limited to the Norfolk Broads and a few coastal areas where they grew in sufficient quantity although much of what is used today is imported. The ends or butts of the reeds are flush so the finished surface appears smooth but the ridge section is usually formed out of straw as it is more flexible. Combed wheat reed is straw which has been specially prepared for thatching by removing the waste so only the stem remains. Long straw was the most common type in the past with the material being used uncombed with the heads still attached. It is laid out and wetted to make it more pliable and is then gathered into yealms, the bundles which are carried onto the roof to be laid. Long straw has lines of liggers (thin wooden rods which hold down the thatch) around the eaves and verges and not just the ridge as with reed. As just the top layer is replaced (coatwork) rather than a complete new covering there are some examples of medieval thatch still in existence under later thatch, with their undersides still blackened by smoke from open fires over 500 years ago.

FIG 1.6: Large medieval, Tudor and early Georgian buildings were usually spanned by a series or pair of short spanned roofs as here at the Guild Hall, Thaxted, Essex.

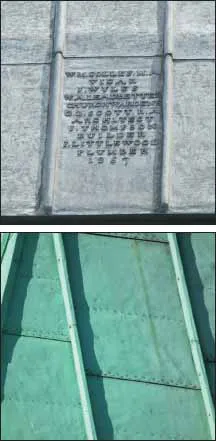

FIG 1.7: Traditional cast lead (top) can last centuries, its durability coming from the salts in its composition which are insoluble and form a protective coating as it weathers. This example from St Mary’s church, Melton Mowbray records its restoration in 1867. Copper (bottom) was often used on towers and domes. It gains a distinctive bright green coating once it is exposed to the atmosphere when acidic pollutants create a chemical reaction which forms copper sulphate. It is this green patina which prevents further weathering.

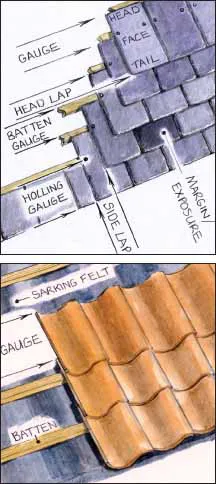

FIG 1.8: Cut away views of a double lap slate roof (top) and a single lap pantile roof (bottom).

FIG 1.9: The roofs of some late 17th and early 18th century buildings featured deep sculptured cornices, white painted dormers with alternate triangular and arched pediments, and a central cupola or lantern as in this example from Bury St Edmunds.

Some parts of the country were fortunate to have sedimentary stones which could be split into thin slabs (fissile) which are known as either tiles, tilestones or slates. These were used from an early date on important buildings but did not become common until the 17th and 18th centuries. In parts of Yorkshire and Derbyshire sandstone was used, which could be naturally split or sawn in a quarry to make stacks of thin slates. These were worked into shape by the knapper or striker who would hammer the edges over a vertical stone and then sort the finished pieces into set sizes which were known by distinctive local names. Limestone roof tiles or slates are a distinctive feature of the Cotswolds and Northamptonshire. Those which naturally formed slabs of even thickness ready to be trimmed to size were referred to as presents, those which had to be split were called pendles. Presents were used as far back as Roman times but it was not until the 16th century that an effective method for splitting limestone to form pendles was discovered. On most stone roofs the tiler would have a random selection of sizes available and would fit the largest ones at the bottom of the roof over the wall and graduate up to the smallest at the ridge. This was because the larger tiles were thicker and hence heavier so were placed directly above the walls for the best support.

FIG 1.10: Traditional plain clay tiles were hand-made and have a bowed profile. Later machine-made types are more regular and square edged. Although the tiles appear like small rectangles only a small portion is exposed as they are double lapped (see FIG 1.8).

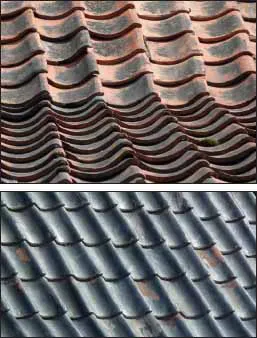

FIG 1.11: Traditional clay pantiles from Norfolk (top right) with their distinctive flat ‘s’ shape profile which covers up the gap with the adjoining tiles so they can be laid single lapped (see FIG 1.8). Glazed black pantiles (bottom right) were an alternative which were used in the 18th and 19th centuries.

FIG 1.12:...