eBook - ePub

Effective Intercultural Communication (Encountering Mission)

A Christian Perspective

- 412 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Effective Intercultural Communication (Encountering Mission)

A Christian Perspective

About this book

With the development of instantaneous global communication, it is vital to communicate effectively across cultural boundaries. This addition to the acclaimed Encountering Mission series is designed to offer contemporary intercultural communication insights to mission students and practitioners. Authored by leading missionary scholars with significant intercultural experience, the book explores the cultural values that show up in intercultural communication and examines how we can communicate effectively in a new cultural setting. Features such as case studies, tables, figures, and sidebars are included, making the book useful for classrooms.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Effective Intercultural Communication (Encountering Mission) by A. Scott Moreau,Evvy Hay Campbell,Susan Greener, Moreau, A. Scott, A. Scott Moreau in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teologia e religione & Ministro del culto cristiano. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Introducing Intercultural Communication

At one time in mission history, it was thought that we simply needed to bring the “pure” gospel to the people whom God has called us to serve. Now, however, many—though not all—Christians recognize that our ideals of the “pure” gospel are always tainted by our own cultural viewpoints. The gospel is not naked; it is always enfleshed in culture if for no other reason than it is expressed in and constrained by human language. Evangelistic tools such as the Four Spiritual Laws, at one time considered the pure gospel, are increasingly regarded as culturally conditioned formulations of the gospel message that do not always communicate well in places where the culture differs from the one in which they were developed.

These realities, and others like them, clearly demonstrate the need for understanding and using principles of intercultural communication in our increasingly multicultural church. In our interconnected world, the ability to communicate well across cultural divides is more important than ever. From business people who travel internationally to short-term cross-cultural workers to long-term church planters, those skilled in understanding how to communicate well are more likely to succeed in the tasks they face.

To help you understand this principle, in chapter 1 we offer important definitions and a model of communication that sets the stage for all the discussion that follows. In chapter 2 we present two perspectives on the history of the discipline: the secular and the Christian. We consider three historical figures who crossed cultures for Christ before the discipline of intercultural communication even existed and present the ways in which Christians currently handle the discipline before examining the ways people approach intercultural communication in chapter 3. Finally, we explore selected issues from a Christian perspective, including the purpose of communication, the missiological implications of intercultural communication, and the more significant challenges that the secular discipline presents for Christians.

1

What Is Intercultural Communication?

In this chapter we lay some of the important foundations for the rest of the book by defining communication and culture, briefly surveying the development of the discipline, offering a model for the process of communication, and exploring the major approaches and themes found in the contemporary discipline.

DEFINING COMMUNICATION

One of the early problems facing the discipline involved the meaning of the two terms at its heart: culture and communication. Neither was clearly or even adequately defined (Saral 1978, 389–90; Kramsch 2002; Levine, Park, and Kim 2007). Although many definitions for each term have been proposed over the decades, there is still no single set on which everyone agrees.

With that in mind, how do we communicate? As early as 1970, almost one hundred definitions of communication had appeared in print (Mortensen 1972, 14). A very general definition is “communication occurs whenever persons attribute significance to message-related behavior.”

This definition implies several postulates (Mortensen 1972, 14–21; compare with Porter and Samovar 1982, 30). First, communication is dynamic: it is not a static “thing” but a dynamic process that maintains stability and identity through all its fluctuations.

Second, communication is irreversible: the very fact that communication has occurred (or is occurring) means that the persons in communication have changed, however subtly. The fact that we have memories means that once we begin the process, there is no “reset” button; we cannot begin again as blank slates.

Third, communication is proactive: in communicating we are not merely passive respondents to external stimuli. When we communicate, we enter the process totally and are proactive, selecting, amplifying, and manipulating the signals that come to us.

Fourth, communication is interactive on two fronts: the intrapersonal, or what goes on inside each communicator; and the interpersonal, or what takes place between communicators. We must pay attention to both fronts to understand the communication process.

Finally, communication is contextual: it always happens in a larger context, be that the physical environment, the emotional mood of the communication event, or the purposes (which may be overt or hidden) behind the communication.

DEFINING CULTURE

As beings made in God’s image and created with the need to learn, grow, and order our world, we learn the rules of the society in which we grow up. Those rules provide us with maps to understand the world around us. None of us escapes the fact that she or he is a cultural creature, and culture has a deep impact on communication.

At the same time, trying to understand any culture is like trying to hit a moving target. Your culture—like all cultures—is not rigid and static. It is dynamic. The rules you learned while growing up will not be identical to the rules you pass on to your own children, especially in technologically advanced settings. Scott still remembers learning how to use a mouse for a computer, while his children acquired the skill at such an early age that they have no memories of learning how to use one.

But what is this thing we all are immersed in that is called “culture”? In 1952, Alfred Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn (38–40, 149) compiled at least 164 definitions of culture for analysis and used close to 300 definitions in their book! One of the reasons culture is so difficult to define is simply because it is so deeply a part of each of us. Every interpretation we make—even every observation—is molded by culture.

One of the most commonly cited definitions is that of Clifford Geertz, who defines culture as a “historically transmitted pattern of meanings embedded and expressed in symbols that are used to communicate, perpetuate, and develop . . . knowledge about and attitudes toward life” (1973, 89). In this concise definition, Geertz indicates both the breadth and depth of culture, helping to frame its richness and complexity.

However we may choose to define culture, it is clear that it is a dynamic (Moreau 1995, 121) and interconnected (Hall 1976, 16–17) pattern that is learned (Hofstede 1991, 5) and transmitted from one generation to the next through symbols (Geertz 1973, 89) that are consciously and unconsciously framed (Hall 1983, 230) and shared by a group of people (Dahl 2004, 4); this pattern enables them to interpret the behaviors of others (Spencer-Oatey 2000, 4).

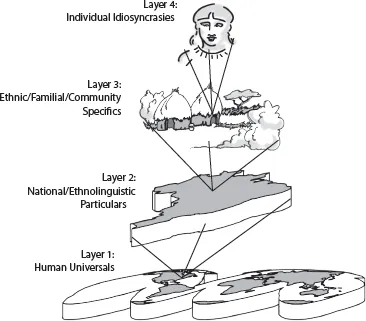

At the same time, culture is neither monolithic nor homogeneous. We can recognize at least four layers of culture (fig. 1.1; see also Hofstede 1991, 6–7; Hesselgrave 1978; Levine, Park, and Kim 2007, 211). The first layer encompasses the universals we all share as humans, including not only such things as language, institutions, values, and sociability, but also our bearing God’s image, our need for relationships, our ability to learn and grow, and so on. We elaborate more on these universals later in the discussion of the common human core.

The second layer includes the specific values and worldview of the largest cultural (or national) unit that people identify as their own. They provide the rule book by which people from that culture operate in meeting their universal needs.

The third layer involves the reality that many of us are part of subcultures within the larger societal or national setting. Much intercultural communication research focuses on the second and third layers.

The fourth and final layer in the diagram reflects that people—even those of the most collective cultures—are still individuals and choose how they will live by cultural rules and regulations. It also reflects that as a genetically unique person who has a unique history, everyone has varying skills in applying his or her cultural rules to the situations of life. This is the layer at which individual idiosyncrasy emerges. Some cultures allow this layer to be valued, while others value less idiosyncrasy and greater harmony and conformity.

FIGURE 1.1

THE LAYERS OF CULTURE

THE LAYERS OF CULTURE

CHARACTERISTICS OF INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION

There are several realities that characterize all communication, whether intercultural or not. They are true of communication in every context (see Moreau, Corwin, and McGee 2004, 266–67). First, everything that we do “communicates”—it is impossible for us to stop communicating (Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson 1967).

Second, the goal of communication is always more than just to impart information—persuasion is behind everything we do. Even a simple “hello” is an act that requests a response or an acknowledgment of your existence and relationship with the person to whom you say, “Hello” (Berlo 1960, 12).

Third, the communication process is generally far more complex than most people realize. Because we have been communicating for so long, and because we do it all the time, we have the tendency to take it for granted (Hesselgrave and Rommen 1989, 180; Filbeck 1985, 2–3).

Fourth, we always communicate our messages through more than one channel, and we always communicate more than one message. At times, these “multiple” messages may contradict one another, causing our audience to respond negatively to our primary concern. At other times, they enhance and reinforce our message, helping to elicit a more positive response from our audience (Kraft 1983, 76).

Fifth, and finally, if we seek to communicate effectively across cultural barriers, the foundational consideration for all our communication should be, “What can I do to build trust on the part of the audience?” (see Mayers 1974, 30–79).

TERMINOLOGY

The discipline of intercultural communication has remained largely within communication studies, though its genesis came from anthropologists (Kitao 1985), and recently calls have been made for anthropology to add its voice to the ongoing discussion (e.g., Coertze 2000). Today the discipline of intercultural communication includes interracial communication, interethnic communication, cross-cultural communication, and international communication (Kitao 1985, 8–9; see table 1.1 for terminology).

WORKING MODEL OF THE COMMUNICATION PROCESS

In figure 1.2 we present a working model of the communication process (see also, e.g., Mortensen 1972; Applbaum et al. 1973; Hesselgrave 1991b, 51; Singer 1987, 70; Poyatos 1983; Dodd 1991, 5; Gudykunst and Kim 1992, 33; Eilers 1999, 242–43; Klopf 2001, 50; and Neuliep 2009, 25). In it we have Participant A, Participant ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1 Introducing Intercultural Communication

- Part 2 Foundations of Intercultural Communication Patterns

- Part 3 Patterns of Intercultural Communication

- Part 4 Developing Intercultural Expertise

- Reference List

- Subject Index

- Scripture Index

- Back Cover