![]()

| CHAPTER ONE |

FROM

SERVICE TO

SOMETHING

ELSE |

IN APRIL 2005, several hundred faculty, administrators, service-learning office personnel, and community partners met in Cocoa Beach, Florida, for the Gulf-South Summit on Service-Learning and Civic Engagement in Higher Education. In its third year, the consortium of universities was a cooperative venture. It had no staff or budget or physical home; it arose out of a need for a regional gathering of theorists and practitioners to network, discuss institutional cultures, and make sense of what many participants hoped would be a permanent shift toward more robust and creative ways higher education would fulfill its public mission. “To Fish or Not to Fish” was the theme of the meeting, but it had nothing to do with the Atlantic Ocean just outside the conference hotel. Most conference themes are innocuous expressions of thematic intent, but this 2005 gathering prompted attendees to listen and respond to faculty colleagues who believed service learning and civic engagement were misguided, inappropriate wastes of time and resources.

Less than a year before the conference, Stanley Fish, former dean of the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Illinois, Chicago, published an opinion in the New York Times titled, “Why We Built the Ivory Tower.”4 Fish was responding to a growing number of university presidents who were signing the Presidents’ Declaration on the Civic Responsibility of Higher Education,5 a document that was shaped, in part, by another national statement, the Wingspread Declaration on Renewing the Civic Mission of the American Research University,6 written by Harry Boyte of the Humphrey Institute at the University of Minnesota and Elizabeth Hollander of Campus Compact, a coalition of colleges and universities committed to the public purpose of higher education. The President’s Declaration proclaimed a “vision of institutional public engagement” that would include greater emphasis on the public mission of universities among faculty, staff, trustees, and students, as well as recognition of civic responsibility in accreditation procedures, rankings, and Carnegie classifications. “We believe that now and through the next century, our institutions must be vital agents and architects of a flourishing democracy,”7 the presidents declared.

Stanley Fish disagreed and imparted a half-century of wisdom to those who work in higher education: “Don’t confuse your academic obligations with the obligation to save the world.” Character formation and civic responsibility are good things, he admitted, but they are not the responsibility of a university, which is to transmit and produce knowledge. To aim for more than that, he argued, dilutes the mission, offers faculty members a platform to espouse their personal political beliefs, and should be the work of people in society other than university faculty. Conference organizers printed copies of the editorial, and throughout the meeting attendees discussed their reactions—mostly in disagreement—using some creative remarks describing successful ways to cook fish. Stanley Fish later extended his argument into an entire book on the subject, provocatively titled Save the World on Your Own Time.8

The disagreement among those in higher education regarding the mission of colleges and universities … could indicate that the experiment of higher education is performing exactly as it should.

The obvious disagreement among those in higher education regarding the mission of colleges and universities might be viewed as an indicator that institutions of higher education are eroding from within. But it could also indicate that the experiment of higher education is performing exactly as it should—shaping and reshaping its self-understanding through discussion and clarification of values that are often in tension with one another, a signature aspect of a process inherent in democratic societies.

While there is disagreement among the academic community regarding how a university’s mission should be realized among citizens, few will deny the long, creative history of universities making knowledge useful and public. The most obvious example is the land-grant system of colleges and universities created by the Morrill Act of 1862, which provided funds for states to create and maintain institutions to teach agriculture and mechanical arts—not to the exclusion of sciences and classics—“to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions of life.”9 Vermont senator Justin Morrill’s vision of increasing access to higher education and investing in the country through the lives of the sons and daughters of farmers and factory workers became a hallmark of higher education in the United States.

The vision expanded with additional federal legislation over the next half-century. In 1887, the Hatch Act created or expanded a system of agricultural experiment stations throughout each state that was connected to the land-grant university, and, most important, connected to the farmers who frequented the stations to receive (and give) practical advice on crops, fertilizers, diseases, and pesky insects. In 1890, Congress passed a second Morrill Act, which forced states to either show that race or color was not a condition of admission for students or create a separate land-grant college for blacks, which many did in the segregated South.

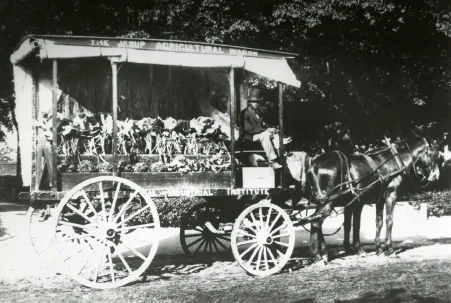

Although federal legislation provided the funds necessary to build schools and curriculum, the desire for communities to become classrooms stemmed from something much deeper than votes in Congress. In rural Macon County, Alabama, for example, soon after his arrival in 1881, Tuskegee Institute president Booker T. Washington made regular overnight trips on horseback to visit farming families. Similarly, in 1896, George Washington Carver, head of the school of agriculture, loaded a buggy full of materials for weekend travels to demonstrate new methods. Within ten years, Carver had developed the fully loaded Jesup Agricultural Wagon, complete with all kinds of modern agricultural inventions and supplies, which Washington called the “Farmers’ College on Wheels.”10 For Washington and Carver, an educational institution could not be separated from the people who could directly benefit from its work.

The Smith-Lever Act of 1914, the last of the four key pieces of legislation that shaped the land-grant tradition, established the cooperative extension system that employs agents affiliated with a university throughout each state. The system is an agreement among federal, state, and county governments, and the army of agents across the nation continue to deliver practical university research to doorsteps, schoolrooms, and community centers in every corner of every state.

While these federal acts shaped a portion of America’s higher education institutions toward systematic dissemination of expertise and research, another federal movement following World War II focused attention on the democratic nature—and promise—of colleges and universities to shape students for more than just professional careers. In July of 1946, President Harry S. Truman convened the Presidential Commission on Higher Education, and he charged 30 civic and educational leaders with making recommendations for expanding higher education to meet a revolution in enrollment, which was due, in large part, to returning soldiers and the G.I. Bill. In addition to access, the commission called for curriculum changes that would provide a general education aimed at developing a civic consciousness and civic skills. The commission condemned racial and religious discrimination in enrollment, although a dissenting opinion written by four commissioners proved that this democratic notion was not held by all.11

George Washington Carver’s Jesup Agricultural Wagon (courtesy of the Tuskegee University Archives, Tuskegee University)

Alfred Bonds Jr., then-president of Baldwin Wallace University in Berea, Ohio, praised the commission’s report but acknowledged the challenge for black institutions. Writing for the Journal of Negro Education in 1948, he surmised that enrollment for African Americans would have to increase by more than 500 percent in order for blacks to be fully represented in higher education by 1960, and “virtually superhuman efforts” would be required in elementary and secondary schools to provide “adequate feeder lines.” But he found some hope in what he identified as the “implicit attitude which runs throughout the entire document: that wholeness of personality needs to become a major objective of higher education.”12 Segregation’s end would come as a result of an emphasis on democracy. Carter Woodson, founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, wrote a scathing indictment of the minority report, saying, “These would-be-liberal-educators have not risen above their medieval constituency with respect to the practice of brotherhood and democracy.”13

The commission report articulated democratic ideals, challenges, and opportunities for higher education, some of which would be realized in the cultural revolution of the late 1950s and 1960s, but the institutionalization of volunteerism and service as a civic commitment in higher education came in 1985 with the establishment of Campus Compact. Founded by the presidents of Brown, Georgetown, and Stanford Universities, along with the president of the Education Commission of the States, the organization began as a response to the media’s portrayal of college students “as materialistic and self-absorbed, more interested in making money than in helping their neighbors.”14 And so, in an effort to correct a public image, Campus Compact was created to assist colleges and universities in the coordination of community engagement. More than 1,100 colleges and universities are members of the coalition.

In 1996, Ernest Boyer, former president of the Carnegie Foundation for Teaching and Learning, offered a conceptual statement on the “scholarship of engagement” that has remained in use for two decades. Simply put, Boyer suggests four modes of scholarship: discovery, integration, teaching, and application. The scholarship of engagement, he says, connects the rich resources of academic institutions to pressing social, civic, and ethical problems present in communities.15 In one sense, Boyer spoke to what many faculty were experiencing: an emerging understanding of the role of the faculty member in a university.

Since the founding of Campus Compact, the number of conferences, consortia, networks, and organizations with a primary focus on civic and community engagement has grown, not only in the United States but also around the world. Journals related to public scholarship are in print and online. Handbooks and anthologies abound. The Carnegie Foundation offers an elective classification for community engagement, a process that requires a significant data collection effort, but that delivers positive outcomes in helping to raise the visibility of engagement and build and strengthen cross-campus relationships. Many universities provide faculty awards for community engagement, and the overall status of the public mission is raised beyond what many pioneers could have imagined 30 or 40 years ago.

The distance between what counts as scholarship and what is produced through collaborative endeavors with communities is both deep and wide.

Despite these gains, which some movement participants might consider modest, the distance between what counts as scholarship in the academy and what is produced through collaborative endeavors with communities is both deep and wide. New faculty are often warned by their department chairs not to venture far from the well-worn path to tenure, yet these junior colleagues are often the ones who bring the most energy around public concerns and a willingness to experiment with new forms of teaching and learning. Community engagement, therefore, is seen as risky, and rightly so, since everyone seems to know someone who had a fabulous body of engagement-activity work but not enough standard publications to warrant the respect of their peers.

The consortium Imagining America: Artists and Scholars in Public Life took on this central issue and published the report Scholarship in Public: Knowledge Creation and Tenure Policy in the Engaged University in 2008, inspired by “faculty members who want to do public scholarship and live to tell the tale.”16 The report offered the following definition:

Publicly engaged academic work is scholarly or creative activity integral to a faculty member’s academic area. It encompasses different forms of making knowledge about, for, and with diverse publics and communities. Through a coherent, purposeful sequence of activities, it contributes to the public good and yields artifacts of public and intellectual value.17

The report includes strategies for junior faculty and departments to employ to make public scholarship count, and while the strategies are reasonable and convincing, the report underscores just how difficult an institutional culture shift can be.

Not long after the release of Imagining America’s Scholarship in Public report, the American Association of Colleges and Universities, with funds from the US Department of Education, convened a National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement, approaching the issue of university mission and active citizenship as an educational priority. The report, A Crucible Moment: College Learning and Democracy’s Future, provides a framework for 21st century civic learning and democratic engagement, and offers the categories of knowledge, skills, values, and collective action as parts of the civic continuum.18 The task force considered its report a “national call to action,” and the refrain throughout is that higher education is more than just workforce training, an idea even most employers would probably agree with.

The national emphasis on public engagement and higher education that is manifested through reports, toolkits, conferences, consortia, and classifications—and in various other iterations—promotes cultural change within individual colleges and universities. At Auburn University (AU), for example, the Guide for Faculty Engagement published by the Office of the Vice President for University Outreach now differentiates between three forms of activity: instruction, expert assistance, and community engagement. Utilizing language from the Carnegie Foundation, AU now defines community engagement as that which “encourages collaboration between the institution and its larger community (local, state, regional, national, global) for the mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge and resources in a context of partnership and reciprocity.”19 The guide also includes definitions and descriptions of activities, such as civic engagement, outreach (engaged) scholarship, extension, and service learning, among others. The addition of new terminology—broadened over the years from just the word “outreach” or “extension”—might indicate an institutional culture change, though not necessarily so.

Throughout the movement, one impetus and anticipated benefit of strengthening the relationship between the public and higher education has related to state funding. In theory, as the public usefulness of universities grows and reciprocity among stakeholders flourishes, legislatures will be compelled to invest in higher education at an equal or higher level. Unfortunately, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the level of state funding in 2014 remains well below where it was before the recession.21 On average, states have reduced funding by 23 percent per student, and nine states have cut spending by more than one-third per student. To manage this crisis, universities have cut expenses and raised tuition, which only deepens the identity of students as consumers rather than citizens. The civic-engagement movement could not weather the fiscal storm of the recession on behalf of universities, and advocates for institutional change now have an e...