1.1 INTRODUCTION

A longtime Christian and student of the Bible posted the following comment about Romans 8:1:

View the difference in versions here! You may want to add this to your NIV. I have an NIV Bible, but when I study, I always compare it to the KJV:

“Therefore, there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (Rom 8:1 NIV).

“There is therefore now no condemnation to them which are in Christ Jesus, who walk not after the flesh, but after the spirit” (Rom 8:1 KJV).

Big difference, huh?

This comment concerns an issue that surfaces throughout the Bible: differences in Bible versions that may affect the meaning. While some Bibles include footnotes to indicate when such differences exist, these notes are not always helpful for readers with no background knowledge of the preservation and transmission of the Bible from its original authors to the current day.

What should we think when we find disagreement between English versions? Which translations are right? Why would translators “change” the biblical text? How can readers make good decisions about these discrepancies between versions?

These questions are important for every student of the Bible, and textual criticism contributes part of the answer. In this chapter we will describe what textual criticism is and why it is necessary. Then we will consider the goal of textual criticism and some of the basic principles for practicing it. Finally, we will evaluate the benefits and limitations of this discipline.

1.2 WHAT TEXTUAL CRITICISM IS—AND IS NOT

Textual criticism can explain some of the differences people notice between their English versions, such as the omission of “who walk not after the flesh, but after the Spirit” in the NIV of Romans 8:1 above. However, other variations in translation are not text critical in nature; instead, they reflect translation technique and decisions made by translation committees. Understanding the differences between text-critical issues and translation issues is an important first step in the study of textual criticism because it helps explain why translations differ and determine when textual criticism will not be helpful.

1.2.1 TRANSLATION TECHNIQUE AND UNCLEAR MEANING

Before a single word of the biblical text is translated, the translation committee, denomination, or other group commissioning the translation decides what their translation philosophy will be. Do they want to produce a “literal” translation, a paraphrase, or something in between? Many variables factor into the translation philosophy, but in general, translators must decide whether they want to preserve the form of the source language as closely as possible or the meaning of the source language as the translator understands it. It is impossible to reproduce languages exactly because the grammar and syntax of each language is different. The rules of the source language—Greek and Hebrew, in the case of the Bible—differ from the rules of English, the target language. Since each language has its own rules, translation requires adapting the rules of the source language to fit into the rules of the target language. Consider the following translations of Isaiah 19:16:

Table 1.1: Translation Options for Isaiah 19:16 |

NASB | NLT | NIV | MSG |

In that day the Egyptians will become like women, and they will tremble and be in dread because of the waving of the hand of the LORD of hosts, which He is going to wave over them. | In that day the Egyptians will be as weak as women. They will cower in fear beneath the upraised fist of the LORD of Heaven’s Armies. | In that day the Egyptians will become weaklings. They will shudder with fear at the uplifted hand that the LORD Almighty raises against them. | On that Day, Egyptians will be like hysterical schoolgirls, screaming at the first hint of action from GOD-of-the-Angel-Armies. |

The differences between these translations of the same Hebrew words illustrate the difficulty of representing information given in one language in a second language.

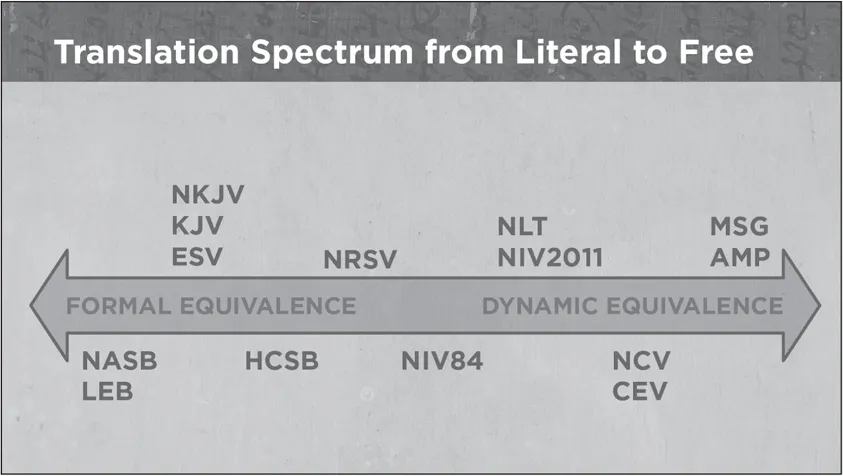

Translation committees decide whether they want to represent in English every word of the Greek or Hebrew, or whether they want to represent in English the meaning of the Greek or Hebrew text. The first option results in what is usually called a “word-for-word” translation or a “literal” translation (though both are impossible in an absolute sense). This approach to translation is called formal equivalence, and translations that aim to be “formally equivalent” try to translate the forms in the source language into equivalent forms in the target language as much as possible. A literal translation can give the reader a good sense of the structure of the underlying Hebrew or Greek, but it can also create an awkward sentence flow and even lead to a failure to grasp the author’s intended meaning. English Bible versions that strive for a word-for-word translation include the LEB, NASB, KJV, and ESV.

With the second approach, translators still make a real attempt to represent the Greek or Hebrew accurately, but they are more willing to “smooth out” the text so that it reflects more readable, idiomatic English. This approach is called dynamic equivalence. The goal is to “produce the same effect on readers today that the original produced on its readers.”1 English versions that employ dynamic equivalence include the NIV, NLT, CEV, and NCV.2

Practitioners of a third translation approach may add explanatory words or phrases that are not in the original text, and they are more likely to rework word order and other aspects of the structure. This option is typically called “paraphrase” (often described as “putting things into your own words”) because the adjustments make significant changes to the structure of the original Hebrew or Greek: “They tend to explain rather than translate.”3 In this method, the translator tries to give the text fresh impact for contemporary readers. Popular English paraphrases include the AMP and MSG.

Thus, the various English versions of the Bible all fall along a spectrum between “highly literal” and “highly paraphrastic.”4 According to New Testament scholar David Alan Black, most important differences in English translations can be accounted for by the translation technique a committee adopts.5

The translation committee makes their translation decisions based on the translation theory they have chosen.6 However, when the translators encounter a passage where the grammar or syntax of the source language is ambiguous, they still must decide how to best render the text in English. Consider the following translations of 1 Timothy 3:6, a verse identifying qualifications for an overseer:

Table 1.2: Translation Options for 1 Timothy 3:6 |

KJV; compare NRSV | NASB | NIV | NLT |

Not a novice, lest being lifted up with pride he fall into the condemnation of the devil. | Not a new convert, lest he become conceited and fall into the condemnation incurred by the devil. | He must not be a recent convert, or he may become conceited and fall under the same judgment as the devil. | An elder must not be a new believer, because he might become proud, and the devil would cause him to fall. |

This is an example of a sentence that has some ambiguity in meaning. The highlighted phrases translate the Greek clause εἰς κρίμα ἐμπέσῃ τοῦ διαβόλου (eis krima empesē tou diabolou):

εἰς κρίμα | ἐμπέσῃ | τοῦ διαβόλου |

eis krima | empesē | tou diabolou |

into condemnation | he might fall | of the devil |

The phrase literally translates as “[lest] he might fall into the...