![]()

IT TURNS OUT THAT TECHNOLOGY DOES HAVE ITS LIMITS. NOT BECAUSE engineers can’t innovate, but because users can’t use. And it is costing tech industries billions in revenue growth every year. The gap between the value that technology products have the potential to deliver and what customers can actually achieve is growing rapidly. Most customers are struggling to keep up, and they usually settle for far less value than they could (and should) get from their purchases.

Unfortunately, most tech companies today lack an effective plan for driving customer success. Why? It’s partly because they can’t get clear of their own product DNA. But it’s mainly because of the organizational constraints imposed on them by their current financial models. Their business strategy simply won’t allow them to do what’s really best for the customer. Sure, they are great product innovators. But delivering true success to customers today requires much more than cool technology—and that is where the breakdown occurs.

A new business model for the tech industry is unfolding—one that requires radically different thinking about the future of services, sales, R&D priorities, and how companies create shareholder value. One that views the use of the product as the beginning of a journey with a customer, not the end. One that defines success in the customer’s terms, not based on revenue recognition rules and customer satisfaction surveys. One that creates competitive differentiation and profits not by adding more features but by getting better results for customers from the features they already have.

The companies that effectively help their customers close this value consumption gap will be the next winners. Feature-based differentiation is fading. Results-based differentiation is rising. Fortunately, many of the pieces needed to deliver this new model profitably are already in place and paid for.

But first, we need to take a step back.

Over the past two decades, the world has seen the digitization of nearly everything. There are the obvious things like computers, software, cell phones, and iPods. But today, cars are digital. So are toys, medical equipment, manufacturing lines, multi-function copiers, TVs, aircraft controls, and musical instruments. And innovations like GPS have made the most low-tech things of all—like taking a hike in the woods—a digital experience.

From the manufacturer’s perspective, the shift to digital is great news. Once a product goes digital, companies can add new and amazing features faster and cheaper than in practically any other form of product development. No factories to build, no dies to cast, no natural resources to deplete. Nearly every industry already has (or soon will find) a way to create a digital component to their product. Maybe it’s in the product itself or maybe it’s in the way you manage the product—like ordering office supplies on a Web site. Beginning on that day, you can count on a rapid proliferation in the features and capabilities of that product. First it is just some basic features. Soon new features will be built on top of the last ones, and so on and so on.

Don Norman, author of The Design of Everyday Things, says there are three primary reasons why companies focus so much of their resources on adding new features into their products.1

1. Customers ask for them. “If the product could just do x, y, or z, we’d buy it.” That also means that for every vertical market, or every horizontal market, we add features. The more markets we want to service, the more features we add.

2. To trump competitors who are also adding features. This is a phenomenon as old as business itself: The product with the most innovative features at the lowest price wins.

3. Engineers want to show they can do it. Product developers and teams have their own sense of pride and accomplishment. That usually takes the form of technical achievements, many of which have created fortunes and notoriety for the engineers and the companies they work for.

From the customer’s perspective, the all-digital world is a mixed blessing. On one hand, adding feature after feature has made products more capable (and in the case of consumer products, cheaper and more fun). On the other hand, all those new features are creating an avalanche of complexity that’s growing bigger and moving faster in industry after industry. And it doesn’t stop with individual products. In fact, one might argue that there’s almost no such thing anymore as an individual product—they’re all just components in larger networks. And the benefit of that network is what customers really want. That, of course, makes things even worse. If you’re trying to get three already complicated products to work together, instead of making your life easier, you’ve got complexity cubed. In order to be successful, customers from global corporations down to consumers need a rapidly escalating degree of expertise and experience. That is true because this avalanche of complexity can be seen everywhere: from complex corporate IT networks to home theater systems to cell phones to medical imaging instruments to, well, you name it.

It all begs the question: How are customers—whether they’re enterprise, small business or consumer, CIO, doctor, shop supervisor or student—surviving the complexity avalanche? According to a number of recent studies, not particularly well. Consider these stats:

• According to a 2009 survey conducted by TSIA, Neochange, and the Sand Hill Group, only 14% of enterprise software deployments are rated as “very successful” by the company IT executives who own them. Of these customers, 12% rate themselves as “not very successful” and 74% as only “moderately successful.”2

• Research group NPD reports that while 71% of mobile phones sold in the United States in 2008 had video capability, only 28% of users were aware they had that feature.3 Awareness among consumers that they can connect their phone to a local Wi-Fi network is probably similarly discouraging.

• According to a survey conducted by British Telecom in 2008, 71% of Britons have up to 10 gadgets lying idly around the home, as they find them too hard to use. The study also shows that 94% of people who experience problems with their home IT are too intimidated or proud to seek expert help. Over 80% of those who have a problem try to fix it themselves, or ask family and friends for advice.4

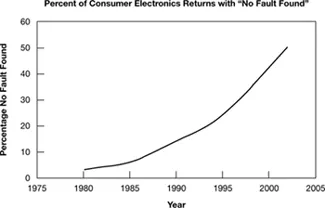

• Only 5% of consumer electronics products returned to retailers are malfunctioning—yet many people who return working products think they are broken. The report by technology consulting and outsourcing firm Accenture pegs the costs of consumer electronics returns in 2007 at $13.8 billion in the United States alone, with return rates ranging from 11% to 20%, depending on the type of product.5 It’s not so much that the product itself didn’t work; it’s that the customer couldn’t figure it out—this is especially true when it is part of the complex network we all know as “home theater.” Here is how consumer returns due to “no fault found” have trended over the last 25 years.6

Source: Brombacher et al. 2005.

FIGURE 1.1 Percentage “no fault found” in modern high-volume consumer electronics.

• Just a few years ago, the BMW 7 series landed up with the dubious distinction of making Time magazine’s 50 Worst Cars of All Time list. Here is what Time.com said: “Perfectly constructed, astonishingly fast and utterly besotted with technology, the big, gracious 7-series had … flaws: The first was something called iDrive, a rotary dial/joystick controller situated on the center console (based on the Windows CE operating system), through which drivers adjusted dozens of vehicle settings, from climate, navigation and audio functions to things like the sound of the door chime. The reason for iDrive and similar systems is that designers were running out of room for switches and instruments. The trouble was that the iDrive was hard to work. Damn near impossible, in fact. Drivers spent many hair-pulling minutes driving to figure out how to add radio presets, for example, or turn up the air conditioning. When confronted with complaints, BMW engineers said, with barely disguised contempt: Ze system werks pervectly. Dis is no problem. Since 2002, BMW has gradually improved iDrive to make it more intuitive, but it’s still a pain.”7

• In another enterprise case, a major software company is reported to have less than one-third of its sold licenses in actual use. In other words, more than two-thirds of what they sold is not being used. Again, it is not because the products don’t work or they are not useful, they simply are not being adopted. In such a case, how many incremental purchases can the company expect from their existing customer base over the next few years? Not many.

What other industries besides tech could possibly survive—let alone thrive—with customer results like these? Could Boeing stay in business if just 14% of the airlines were “very successful” at getting pilots and crews to use the features of the plane? What about John Deere with its tractor customers? What about your company? Would you tolerate only 14% of your customers being “very successful”? Probably not.

In their defense, tech manufacturers and software companies—both business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumer (B2C)—have tried creating voluntary technical standards to improve user interfaces and interoperability. Over the years (and years and years) standards do tend to happen and are hugely beneficial. But this long delay means that standards really haven’t done much to hold back the complexity avalanche. Standards simply can’t keep pace with the rapid proliferation of great ideas from smart companies and the features and capabilities that flow from them. For the first time, some tech customers are actually interested in having features taken out!

You will notice throughout this book that we bounce between product categories, industries, customer types, and price points. That is because the complexity avalanche is not just happening here or there; virtually every technology category is in its path. Many people would argue that this problem was once the domain of big enterprise IT customers. Now it’s happening in the home. And if it hasn’t already, it will soon happen to you.

THE CONSUMPTION GAP

So here’s the dilemma facing technology companies large and small: If your end customers can’t figure out how to use your product or they can’t get it to work in their network or they can’t change their business process to adapt to its features, it has little or no value to them. No amount of slick graphics, flashing lights, and jaw-dropping technological advances is going to change that. The ultimate goal for technology companies is no longer just to sell products. In order to make customers successful, companies must move beyond that thinking. The ultimate goal today is to enable customers and their businesses to get full value out of the product, the value it has the potential to provide.

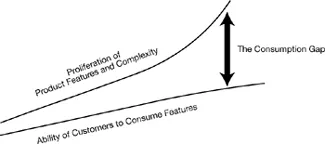

Source: TSIA

FIGURE 1.2 The Growing Technology Consumption Gap.

The difference between the value the product could provide to the customer and the value it actually does provide is what we call the “consumption gap.” And the consumption gap is growing, not shrinking. We’re talking about the manufacturing company who has only half its plants using its scheduling application, the IT guy who can’t use important system utility functions in the network management tools, the MRI tech who takes twice as long as his peers to do complicated scans, the average digital camera user who has only a small percentage of digital images in print, or the fire captain who can’t use the central dispatch system in the fire truck at all. Solving problems like these is a challenge that should rally your company no matter what its role in the supply chain. Whether your company makes tech products, relies on tech products, or sells them direct to customers, the consumption gap is a growing threat to your business.

Here are five powerful reasons why you and your company might care deeply about the consumption gap facing your customers:

1. It might be limiting the size of your market to only the technically advanced, “early adopters.” They are the only ones willing and able to figure things out.

2. It might be slowing the rate of repurchase by your existing customers because they aren’t using what they already own.

3. It might be increasing your cost of sales and reducing your product margins on repeat purchases because the value of their old version of the product wasn’t fully realized.

4. You might be leaving service revenue and profits on the table and missing a huge differentiation opportunity. Customers want help and will pay to get it.

5. If your sexy new features aren’t being used, they aren’t much help against the competition. There are multiple examples of products that compete effectively with other products boasting twice as many features. Both have the few features that customers actually use. The rest are not just useless, they are actually negative to some customers because they add clutter to the interface and steal system capacity. And they cost money to develop and maintain, used or not.

We are going to talk about these realities (and others) in different industries throughout this book because we see...