![]()

PURGATORIO

![]()

CANTO 1

Self-Help or Divine Help

The Damaging Power of Sin

Turning Points in Our Lives

The Necessity of the Church

In many bookstores, the section labeled “Spirituality” is often filled with an astounding variety of self-help books. The assumption seems to be that the spiritual life is fundamentally something we must do for ourselves, but something we rarely get around to doing. And so we need the encouragement of such books to inspire us to get down to business. And although we do need to take an active part in our spiritual lives, much of the work that needs to be done (in fact, the most important work) is beyond our ability. God himself teaches us that he takes an active role in our spiritual lives, in fact a leading role. “Thus says the LORD: ‘In a time of favor I have answered you, in a day of salvation I have helped you’” (Is 49:8). Salvation is God’s work. He is our help and our salvation.

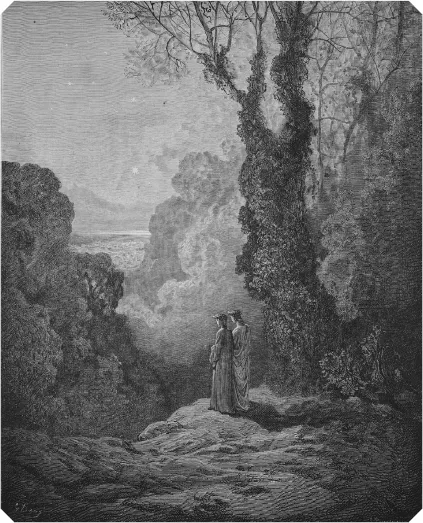

1 When Dante left the underworld at the end of the Inferno, he emerged from the darkness, and the first things he noticed as he climbed out of the pit of hell were the stars. There, in hell, he had been separated not only from heaven but also from the heavens. He had been with the people who had chosen to dwell in darkness eternally, but now he is beginning to see the light. After being light-deprived, it seems fitting that Dante begins Purgatorio with a description highly colored with astronomical imagery. Dante is glorying in his newfound light, a light that delights his eyes and his soul, a light that promises to guide him from the darkness of sin to the splendor of heaven.

The light Dante experiences seems more than mere physical light. It is an image of the grace that enables all activity in purgatory. Hell was deprived of all that is supernatural. Grace was entirely absent. But purgatory is different. Here, God’s light illuminates everything, giving it not only guidance but also strength, “fostering love like rain.”

25 The constellation of the Southern Cross rules the Southern Hemisphere’s sky. The light here is not merely light; it is a symbol of Christ’s triumph and our salvation. The Northern Hemisphere, considered by medievals to be the inhabited part of the earth, is considered a widower for not being able to see this constellation. It has been condemned because of sin to be separated from this natural sign of God’s grace. Dante himself is that widower, and so are we. There is so much that we don’t see because of the darkness of sin, so much that we don’t enjoy because of the twistedness of our natures, so much that we think is impossible because of our lack of awareness of God’s constant activity in our lives.

37 The first person Dante and Virgil meet after climbing out of the pit is an old and venerable man. The reflection of the Southern Cross illuminates the old man’s face. Grace gives him “a brilliant gleam.” We see how the hope of salvation, a hope that the grace of the cross brings, illuminates everything, makes everything shine or gleam. It transforms everything.

SIN is an action against God’s commandments. But what remains when the action is over? Is it simply a black mark in the book of life? Demerit points on our heavenly record? No, the reality of sin is much more serious and real than that. Sin causes objective damage to our souls. It changes us, twisting and distorting us, causing us pain and suffering. If we could see our souls with spiritual eyes, we could witness for ourselves the horrible, disfiguring effects of sin. We could observe for ourselves the source of our sufferings. Sin is not a legal fiction. It is a spiritual fact.

40 In the Inferno, Dante was often mistaken for a damned soul in those circles punishing sins to which he was inclined. The damned souls and the demons and beasts who dwell with them possess a sort of spiritual discernment, allowing them to “read” Dante’s soul. Merely by looking at him, they saw his bad habits and sins. They could see that he was on the path that would lead him to join them one day in hell.

The old man has the same sort of spiritual discernment. He identifies Dante as someone on the road to damnation and so concludes that he must have “come up the blind stream to flee the prison of eternity.” In a way, the old man is right. That is precisely what Dante’s journey is about. He has been taken on this unheard-of path so that he can escape hell not merely now but, more importantly, at the time of his death.

48 The old man clearly feels rather territorial: “You, the damned, come to my rocky shore?” As we shall learn, he is a sort of official here, greeting and directing the newly arrived souls. He has seen innumerable souls arrive here, but none who had arrived in the way Dante and Virgil did. What is going on? It is his responsibility to find out. He is Cato, and his story (and his reason for being here himself) will be revealed gradually.

51 Dante kneels and bows his head before Cato, showing the importance of humility in purgatory. His action seems almost liturgical. This liturgical tone will pervade the entire journey through purgatory. We will see that much of purgatory is spent on one’s knees. It is not clear whether Virgil merely tells Dante what to do or also offers this sign of respect to Cato himself, but his joining with Dante would seem to be quite fitting. Even on natural terms, Cato is a man deserving of our respect and veneration.

THERE are moments in our lives that at first seem no different from thousands of other moments. It might be someone we meet or an old friend with whom we reconnect. It might be a strange coincidence of events. It might be a whim that suddenly rises up in our hearts. They might seem like ordinary events, but for some reason, these are different. These choices will lead us in an entirely new direction, for better or for worse. These are turning points that we might come to appreciate only in retrospect. How did something that seemed so small at the time end up having such a profound effect? These moments are a reminder that the course of our lives is not something that we design and execute. There is a plan that is bigger than ourselves, a plan that encompasses every minute detail, a plan for our good.

52 Virgil explains to Cato that this journey began by a visit he received from a blessed soul from heaven. This woman who came to speak with him, Beatrice, was not acting on her own, as we learned in Inferno, canto 2. The Blessed Virgin Mary herself was the one who instigated this project for Dante’s salvation. She then asked the cooperation of St. Lucy, who then asked Beatrice. Dante’s appearing on the shores of Mount Purgatory is not the result of an infernal jail break. He is here as the fulfillment of a heavenly plan.

60 “… very little time to turn.” Dante’s journey is somehow a matter of life and death, something urgent. We aren’t told exactly why, but the impression is that if the three ladies from heaven had not intervened when they did, Dante would have been a lost soul. Not only would he have continued in his ways, but also those ways wouldn’t have lasted for long. Death and damnation were just around the corner. Something needed to be done immediately.

71 “He seeks his freedom.” Virgil expresses Dante’s journey as a battle for freedom, a fitting way to introduce him to Cato. Cato had died by suicide rather than violate his conscience or renounce his freedom. He is viewed by Dante as a sort of martyr to freedom of conscience. Dante is now willing to do whatever it takes to regain his own freedom. Liberty is the goal of purgatory: here, everything reminds us that “the truth shall set you free.” This realization changes everything. It will, for example, affect the attitude of the holy souls to their penances. They are not undertaken in a begrudging spirit but with an awareness that they are necessary for their freedom, for their happiness. They are eager to get down to the business of preparing their souls for heavenly bliss.

85 Virgil has tried to win over Cato by appealing to his love for his wife, Martia. He has been a devoted husband; it seems only natural to Virgil to promise to take greetings to her when he returns to limbo, where Martia spends her eternity too. Dante’s depiction of limbo is his own unique invention. There he gathers together the Church’s traditional teaching about the bosom of Abraham (often called the limbo of the fathers), the theological speculation of a limbo for unbaptized children, and his own invention of an eternal destiny for virtuous pagans. Cato’s wife, Martia, is one of these virtuous souls who lacked the grace needed to enter heaven.

But Cato lets Virgil know that he has misjudged his loyalties. Those in hell (and limbo is part of hell) have no influence over those in purgatory. Natural bonds have been replaced by the communion of saints. The wishes of Martia, Cato’s beloved wife, count for nothing, but those of Beatrice, a complete stranger, are like a command. “Beg in her name: there is no more to say” (93).

C. S. Lewis, who in addition to being a popular author was a scholar of medieval and Renaissance literature, presents a similar idea in The Great Divorce. There, one of the souls visiting from hell tries to make the souls in heaven miserable out of pity for the sufferings of the damned. His wife, Sarah Smith, tells him that the misery of hell cannot have veto power over the bliss of heaven.

Regardless of Cato’s natural sympathies and loyalties toward Martia, he is now a citizen of the heavenly city; he might still be in exile in purgatory, but heaven is where he now belongs; the bonds of charity are all that matter now. The wishes of the citizens of heaven are his delight.

THE Church has consistently taught that the Church Christ founded is not merely an optional assistance on the road to salvation. It is necessary. The Second Vatican Council “teaches that the Church, now sojourning on earth as an exile, is necessary for salvation.”2 Every soul that is saved, every soul that ultimately makes it to heaven, will do so through some sort of union with the Church. Although this might sound like an arrogant thing for the Church to define, it is really theologically rather straightforward. Christ is the pathway to heaven; he is the one whose death pays the price for our sins. No one can be saved without being united to Christ as a member of his body. But if you are united with Christ and I am united with Christ, then we are united together in him. That is what constitutes the Church. We cannot belong to Christ without somehow belonging to the Church. Salvation is a communal action, an ecclesial event. No one is saved apart from the Church.

94 Entry into purgatory requires a sort of ritual cleansing and preparation. The pilgrim must be clearly identified by the reed around his waist (just as medieval pilgrims could be spotted by their distinctive garb), and the grime of hell must be washed away.

This stands for the ritual entry into the Church, for everyone who enters purgatory enters the Church as well. The white baptismal garment that signifies the new life received at Baptism is here replaced by the pilgrim’s reed. The cleansing waters of Baptism that wash away original and personal sin are seen in the dew that descends upon purgatory.

Cato insists upon this baptismal imagery. He is the one who assures that all new arrivals follow the proper procedure. But he himself was a pagan. He was born and died before the coming of Christ and the possibility of baptism. What is he doing here? The membership in the Church, the Mystical Body of Christ, that is necessary for our salvation must somehow encompass Cato too.

102 The reeds are the only plants to grow on the mountain’s shores. They are symbols of humility, often associated with those on pilgrimage, a sign of being consecrated to God. Because they bend (thus the connection with humility and bowing down low), they can withstand the beating of the waves. Only those souls who have that same characteristic will be able to withstand the rigors of life, both in this world and in purgatory. The spiritual life must be built on the foundation of humility. The “stiffened trunk” of pride cannot survive here.

112 As Virgil and Dante begin their ascent, the first streaks of dawn appear in the sky. It is Easter morning. The paschal mystery is complete, making spiritual progress possible.

124 Dew is a symbol of God’s grace. In Advent, the Church uses the hymn Rorate caeli desuper. We ask heaven to rain down the Just One like the dew. In the wilderness, God fed the people of Israel with manna that came down like dew. Think also of Gideon and the fleece covered in dew, by which God calmed Gideon’s doubts.

Grace is the foundation of everything here in purgatory. With that dew of grace, Virgil cleans the grime of hell from Dante’s face. All cleansing in purgatory is made possible by grace. This is not a place of self-help or Pelagian self-reliance. Notice that Dante is not even allowed to wipe his own face. He receives that cleansing as a gift.

Dante’s true color, until now obscured by the grime of hell, is now exposed. Being cleansed from guilt and purged of our bad habits reveals the true person buried beneath the dehumanizing grime of sin. Growth in holiness is a growth towards our true individuality, not a denial of it.

135 The reed grows back as soon as it is picked. Since the reed is necessary for beginning the climb, this immediate replacement of the reed Dante used shows the unbounded generosity of God’s forgiveness, making available whatever is necessary for our spiritual progress. The fact that Dante has taken a reed for his own use will not limit the possibilities of another soul. God’s grace will be there as fully and generously for the next soul to arrive as it was for Dante.

_______________

2 Lumen Gentium, 14.

![]()

CANTO 2

Spiritual Inertia

Eagerness for Our Heavenly Home

Human Love Purified

The Distracted Life

Getting started is indeed half the battle. Call it inertia or procrastination—sometimes it can be an enormous struggle to begin work, especially when the work promises to be long or taxing. We come up with excuses; we avoid thinking about it; we distract ourselves with other things. Putting things off is a minor art form. It can be humbling to realize how unable we are to get ourselves moving. Sometimes it takes something from the outside, an external stimulus, a firm shove in the back, to get us moving. This tendency can be even greater in the spiritual life. The tasks are often not as visible as our everyday work is, and there always seems to be plenty of time to get around to it. We do have plenty of time, don’t we?

7 The poem begins with a reference to the dawn, the rising sun now peeking above the horizon, a symbol of God’s goodness and grace poured out upon his creation. Because of the geography of a mountain, progress here will bring us closer and closer to the light. The transformative activity of this light (it is more than merely a source of illumination) is a recurring theme in Purgatorio. The imagery of dawn is made even more powerful when we realize that this is Easter morning, the time of the Resurrection of Our Lord and of his triumph over death and sin.

10 Dante has difficulty actually getting started on the journey up the mou...