- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A culmination of decades of research on field notes, plats, correspondence, legislation, and observations of surveyors, cartographers, government officials, military commanders, Native Americans, early settlers, and land speculators, this volume is the first of its kind in nearly a century. Interweaving the history of Ohio and biographies of the individuals associated with surveying and mapping, Blazes, Posts and Stones is a must-read book about the non-sequential development of Ohio lands and its subdivisions. The book is complete with maps and figures and provides technical descriptions of them. An excellent resource for county engineers, but also for those who have an interest in Ohio history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Blazes, Posts & Stones by James L. Williams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Land Act of 1796

AN ACT PROVIDING FOR THE SALE OF LANDS OF THE UNITED STATES, IN THE TERRITORY NORTH-WEST OF THE RIVER OHIO, AND ABOVE THE MOUTH OF THE KENTUCKY RIVER, MAY 18, 1796

Given its experience with selling tracts of one million acres or more to the Ohio Company of Associates, The Scioto Company, and John Cleves Symmes, Congress gave up on the idea of conveying large grants to private individuals or companies. Symmes had evoked the distrust of Congress when he persisted in conveying land beyond the boundaries of his grant of 1792.1 In the spring of 1796 Congress returned to the policy of federal subdivision of the Northwestern Territory. Without reference to the Land Act of 1785, which had expired with the Continental Congress under the Articles of Confederation, the US Congress began debating a new land subdivision policy. Again, Hugh Williamson of North Carolina led the discussion and was supported by Elias Boudinot of New Jersey. President Washington signed the act on May 18, 1796. The immediate result of the new act was the reopening of sales in the Seven Ranges. One quarter township was sold at Philadelphia and by June 1798 two townships had been sold at Pittsburgh.

The Land Act of 1796 reestablished the basic principles of the Act of 1785 and became the legal basis of all subsequent US Public Land surveying. It also established the office of Surveyor General.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, that a Surveyor General shall be appointed, whose duty it shall be to engage a sufficient number of skillful surveyors, as his deputies, whom he shall cause, without delay, to survey and mark the unascertained outlines of the lands lying northwest of the river Ohio, and above the mouth of the river Kentucky, in which the titles of the Indian tribes have been extinguished, and to divide the same in the manner hereinafter directed; and shall have authority to frame regulations and instructions for the government of his deputies; to administer the necessary oaths, upon their appointments; and to remove them for negligence or misconduct in office.2

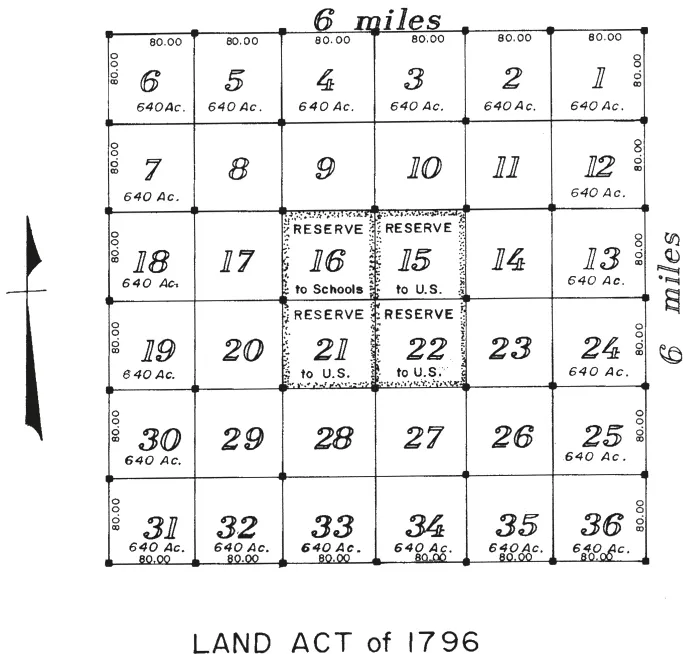

The Act of 1796 once again called for north-south lines to be run by the “true meridian.” East-west lines would cross them at right angles, so as to form townships of six miles square. The corners of each township were to be marked with progressive numbers from the beginning; “each distance of a mile between the said corners shall be also distinctly marked with marks different from the corners.” One half of the townships, taking them alternately, were to be subdivided into sections, containing, as nearly as possible, six hundred and forty acres each, “by running through the same, each way, parallel lines, at the end of every two miles; and by marking a corner, on each of said the lines, at the end of every mile; the sections shall be numbered respectively, beginning with the number one, in the north east section, and proceeding west and east alternately, through the whole township, with progressive numbers, until the thirty-sixth be completed.”3 This is the beginning of the “Two Mile Blocks” which brought surveying control inside each township. While not setting every section corner, it did set three of the four corners on each section. The reason for the change in the section numbering is not clear. Perhaps the Congress of 1796 did not know the system for numbering lots in the Act of 1785.

Figure 6.5-1. Congress in passing the Land Act of 1796, changed the numbering of sections and the four reserved sections in each township. The Act also provided for the surveying of the “Two Mile Blocks” inside each township. This brought federal surveyor’s control in the townships with three corner posts set on each and every section.

Deputies were now required to mark the section number on trees at the corner or on trees nearby and mark the township number above it. Deputies were also required to keep field books describing the corner trees and the numbers marked on them. Field books were to also note salt licks, mill seats, water courses, and the quality of the land. Field books were to be returned to the Surveyor General upon completion of the survey. The Surveyor General must make a plat from these field books, keep one copy in his office, and send copies to both the place of sale and the Secretary of the Treasury.

All lines were to be measured by a chain of two perches (thirty three feet) long. These chains were to be adjusted to a standard chain kept just for that purpose. Chain carriers were to be sworn in by the deputy surveyors. Although the two- pole chain was to be used in the field, the unit of measure on the plat was to be the 66-foot chain. This continued the scale of one inch equaling forty chains that had been the practice of Hutchins’ and Putnam’s surveyors in 1786 and 1788.

The Surveyor General was also to delineate the line of General Wayne’s Treaty with the Indians. He was to “survey and mark the unascertained outlines of the lands lying northwest of the river Ohio, and above the mouth of the river Kentucky, in which the titles of the Indian tribes have been extinguished.”

Also, the United States reserved the four center sections 15, 16, 21, and 22 of each township for future disposal. It should be noted that when Putnam sent his deputies back into the Old Seven Ranges attempting to rework some of the section lines, they reserved the four center sections in some of the townships. Other townships in the Old Seven Ranges contained the federal reserves of the Act of 1785.

The four principal areas for the Surveyor General to concentrate the work of his deputies were: the Military Reserve, the lands west of the Seven Ranges to the Scioto River, the land west of the Great Miami River, and the lands south of the Connecticut Reserve to the Geographer’s line. Lands west of the Great Miami were to be sold at Cincinnati. But lands between the Scioto and the Seven Ranges were to be sold at Pittsburgh and the same for the lands south of the Connecticut Reserve. All lands were sold for not less than two dollars per acre.4

The Act of 1796 further stated “that all navigable rivers, within the territory to be disposed of by virtue of this Act, shall be deemed to be, and remain public highways: And in all cases, where the opposite banks of any stream, not navigable, shall belong to different persons, the stream and the bed thereof shall become common to both.”5

The Surveyor General’s salary was two thousand dollars per annum. The President of the United States could set the compensation of assistant surveyors, chain-carriers and axemen, provided that the whole expense of surveying and marking the lines did not exceed three dollars per mile. The Surveyor General, assistant surveyors, and chain-carriers were to take an oath or affirmation to faithfully perform the duties assigned to them by the United States of America.

The Act was signed by: “Jonathan Dayton, Speaker of the House of Representatives, Samuel Livermore, President of the Senate, pro tempore, George Washington, President of the United States and approved May the Eighteenth, 1796.”

President Washington chose Simeon DeWitt, Surveyor General of New York and former Geographer of the Continental Army, to be the first Surveyor General. DeWitt declined the President’s offer. Israel Ludlow applied for the position but was passed over by President Washington. Anthony Wayne was passed over by the President. Rufus Putnam of Marietta, Northwestern Territory and Superintendent of Surveys for the Ohio Company, was next offered the position and Putnam accepted. On September 30, 1796 Putnam received his commission as Surveyor General of the United States from Secretary of State Timothy Pickering.6

The Land Act of 1796 did not address convergence of the meridians and Putnam was not proficient enough at mathematics to solve it. He was, however, the most experienced surveyor and survey manager in the western country who possessed a proven record in the Ohio Company’s Purchase. Although the surveyors were supposed to run true meridians (i.e. correct for magnetic declination), Putnam in order to avoid a long triangular gap between their new work and the work of 1787, instructed his deputies to align their surveys to the westerly line of the Old Seven Ranges. Under Putnam’s direction, the Ohio Company surveyors had worked under a contract system, where each surveyor was assigned a specific line or township to measure and mark. Putnam continued that system while he was Surveyor General.

Even though the Act of 1796 instructed the surveyors to mark trees at or near section and township corners with the appropriate numbers, it did not specify the exact markings to be used. Therefore, Putnam’s deputies perpetuated the marking system first used by Israel Ludlow on the Seventh Range of the survey of 1787. Ludlow marked line trees with three notches on the north and south for lines measured in a westerly direction and three notches on the east and west for lines ran southerly. He notched his posts with the appropriate number of cuts to reflect the number of the section or township. He blazed township corner trees and witness trees and stamped the township number into the blaze and notched the trees accordingly. The system was carried across the Northwest Territory and beyond by US deputy surveyors.

THE GREENEVILLE TREATY LINE 1797–1799 ACCORDING TO GENERAL WAYNE’S TREATY OF 1795

“Israel Ludlow is a man of ability, diligence, integrity and great energy” stated Thomas Hutchins, Geographer of the United States in 1786. In the Seven Ranges survey of 1787, it was Ludlow who volunteered for the survey of the Seventh Range, the one most exposed to random strikes by Indian banditti. In 1789 Ludlow surveyed eighty miles up the Scioto and then ran a line easterly to the Seventh Range through the very heart of Wyandot and Delaware Indian country. Likewise, Ludlow had undertaken the survey of the Ohio Company’s Purchase boundary in 1791, after General Harmar’s failed expedition against the Miami Indians. After General St. Clair’s defeat on the Wabash in November 1791, Ludlow again took to the field. He surveyed the boundary of the Symmes Purchase when the Indian threat was greatest. In 1794, Ludlow again risked his life to survey north of Symmes Purchase.

Surveyor General of the United States, Rufus Putnam had only one deputy surveyor in mind for surveying of the Indian Boundary Line and that was Israel Ludlow. In March 1797 Ludlow, who was a captain in the Hamilton County militia, received Putnam’s invitation to measure and mark this line.7 Ludlow immediately began assembling a group of men to undertake this dangerous assignment. Ludlow’s party included his chain carriers William C. Schenck and Israel Shreeve, both from New Jersey, five axe-men, and a twelve-man escort. They departed Ludlow’s Station at Mill Creek on May 20th with a small herd of cattle and made their way to the forks of Loramie’s Creek, where once had stood Peter Loramie’s store.8 Ludlow and his men made camp there on the first day of June.

There they waited for the Indian chiefs who were to accompany them and watch the line be marked in a “conspicuous manner.” Each day they watched the northern horizon for signs of the Indians and each day they were disappointed. In the meantime their supplies began to diminish. When no chiefs had appeared by the 15th of June, Ludlow administered the oath to his chain carriers: “You and each of you will to the best of your ability, well and truly execute the duties assigned to you as chain carriers while employed in the measuring the boundary line now to be surveyed between the United States and the several Indian tribes according to the late treaty by General Wayne and a true return of the several distances give as shall be required of you. This you solemnly swear as you shall answer to God on that Great Day.”9

After writing to Ludlow in March, Putnam wrote to General James Wilkinson, commander of the US Army at Fort Washington, to ask Wilkinson to invite some influential Indian chiefs to accompany Ludlow along the line and to provide an armed escort for the party. Although Putnam had offered the survey to Ludlow in March, he had not heard from him by May 6 regarding this assi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Drawings, Plats, and Maps

- Author’s Note

- A Note on the Maps and Plats

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Land Act of 1785

- The Indian War 1790–1795

- The Land Act of 1796

- Afterword

- Index