- 156 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A minute-by-minute and day-by-day account of the elite 101st Airborne's daring parachute landing behind enemy lines at Normandy is accompanied by firsthand accounts from Airborne veterans and forty incredible, previously unknown (let alone published) color photos of the "Screaming Eagles" at Normandy and in Great Britain prior to the invasion. Accompanying these remarkable D-Day color Kodachromes—which were unearthed in the attic of an Army doctor's daughter—are more than two hundred black-and-white photographs from 101st survivors and the author's own private collection. This is an unprecedented look at an elite fighting force during one of the last century's most crucial moments.

Information

CHAPTER 1

TRAINING

AND

MANEUVERS

Benjamin Franklin predicted airborne warfare long ago, writing that “ten thousand men descending from the clouds might not in many places do an infinite deal of mischief, before a force could be brought together to repel them.” Franklin’s eighteenth-century idea envisioned two men each in “five hundred balloons” as a means of deployment long before airplanes or parachutes became a reality. It was perhaps fitting that the first successful airplanes would be tested, invented, and flown by this visionary founding father’s countrymen.

The very first use of parachute jumpers as soldiers was slated to involve U.S. infantrymen of the 1st Division as early as 1918, but the armistice ending World War I forestalled that proposed mission. American military parachutists would eventually be deployed in combat when the 509th Parachute Battalion dropped into North Africa in 1942.

In the interim years, parachuting had mostly been confined to amusement rides at world’s fairs and stunt descents at air shows. Despite small-scale experiments in the late 1920s, the U.S. military didn’t take another serious look at the potential of deploying armed parachute forces until the Russians made mass drops of paratroopers in the late 1920s, the U.S. military didn’t take another serious look at the potential of deploying armed parachute forces until the Russians made mass drops of paratroopers in the late 1930s.

The 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment began in 1941 as a battalion. It was not upgraded to regimental size until August 1942. When the 101st Airborne Division was activated, the 502nd became the original parachute infantry regiment (PIR) of the division. In this battalion-era photo, new arrivals, mostly men from Ohio, are being issued jumpsuits on June 20, 1941. Two of them, identified as Rigsby (fifth from right) and John Q. Young (far right), later became members of Company G in the 502nd Regiment. Rigsby was killed on a night patrol in Holland—soon after jumping there—in September 1944. Rigsby’s cousin, Gene Baker, was a platoon sergeant in the same company. Acme Newspictures, Atlanta, GA H/502 PIR marching at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, in 1943. In the right foreground is their company commander, Capt. Cecil L. Simmons, also known as “Big Cec.” Simmons had been a uniformed police officer in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and a member of the Michigan National Guard before entering federal service. Also recognizable in the photo are Sgt. Elden Dobbyn and Sgt. J. B. Cooper. The troopers have been issued M42 jumpsuits with white nametapes and are carrying old-style gas masks slung under their left arms. Newer assault-type gas masks were issued for combat jumps into Normandy and Holland. Signal Corps via C. L. Simmons

With war clouds gathering in Europe, the German army experimented with paratroop forces prior to their invasion of Poland in late 1939. The Germans demonstrated during their blitzkrieg in the west that airborne forces deployed in small groups could seize key objectives such as bridges and even fortresses. The invasion of Crete further demonstrated to the world—albeit at a costly price to the German invaders—what airborne troops could do. The Americans and British soon copied the German example with experimental, small-scale forces of their own. A U.S. “parachute test platoon” was formed in 1940 and began testing various equipment and parachute types.

Whereas the Germans made paratroopers part of their Luftwaffe, the Americans decided that the primary job of its paratroopers would involve ground combat. After the initial experiments of the test platoon, a number of volunteer parachute battalions were activated and men were accepted into them on a strictly volunteer basis.

In addition to the glamour of belonging to an elite, death-defying unit, volunteers would be paid fifty extra dollars per month as jump pay for enlisted men and one hundred extra dollars per month for commissioned officers. The earliest battalions were the 501st at Panama and the 502nd at Ft. Benning, Georgia (later at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina). Glider infantry and artillery units were also soon formed and a new tradition of elite warfare had been born in the U.S. Army.

A practice jump at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, in 1943. The troopers pictured are from I/502 PIR. Their platoon leader (later company commander), Lt. Ivan Ray Hershner, is seated at left near the exit door. Lieutenant Smith is standing at the far end of the aisle near the bulkhead. In this photo, a lot of Airborne equipment is visible, including M2 jump helmets, reserve chest-pack parachutes, padded cases containing weapons (tucked behind the reserve chutes), and a coiled “jump-rope” used to climb down if a trooper landed in a tree or on a rooftop. Signal Corps via Ivan R. Hershner

The famous 82nd Infantry Division at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, was the first large-scale unit marked for airborne status. In World War I, the 82nd had been the home outfit of the legendary Sgt. Alvin York. In 1942, the new division was loaded with a combination of old army regulars and recently conscripted draftees brought into the army by selective service. After Hitler’s forces attacked western Europe and then invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, it seemed only a matter of time before the United States became directly involved. Initially, U.S. Airborne tacticians visualized small-scale deployments of platoons, companies, or battalions of paratroopers with limited objectives. But deployment of entire divisions to open the second front became a more and more appealing idea.

As early as 1942, Allied planners were conceiving and designing ways to penetrate Hitler’s Atlantic Wall with test raids on the German-held coast. The Red Army was engaged on a massive scale along a two-thousand-mile front, and Russia was clamoring for the Allies to relieve some of the pressure by advancing on the Nazi homeland from the west. Starting methodically in North Africa to drive Rommel’s Afrikakorps from the desert, the western Allies pushed north into Sicily, then staged for multiple landings along the coast of Italy. Brutal fighting in the Mediterranean theatre eventually slowed to a long war of attrition.

The way into Germany obviously lay farther to the north, with a massive crossing of the English Channel into France. For this epic invasion to succeed, division-size airborne units in unprecedented numbers, along with sea-landing forces, would have to secure lodgment. These units, thousands strong, would jump or glide into the areas behind the Nazi-held coastlines to attack the beach defense from behind, paving the way for the seaborne landings. The success of those debarking on the shorelines required weakening and distracting the German defenders to minimize casualties.

Back in the United States, massive drafts of military-age males in 1940 and 1941 had swelled the ranks of the peacetime army, but the picture came clearly into view after Imperial Japan struck the U.S. naval fleet at Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

On December 8, the United States had officially declared war on Japan. Although Germany’s ally had been the aggressor, Germany declared war on the United States only a few days later, December 11. Some of the early parachute battalions had already been training for months before America’s entry into World War II. Members of the 501st Battalion were dispersed as cadre to train massive numbers of future paratroopers, and the 502nd Battalion would be enlarged into a regiment. The 82nd Infantry Division at Camp Claiborne was divided in half, with part redesignated as the 82nd Airborne Division, and part formed as the new 101st Airborne Division, which was activated on August 15, 1942.

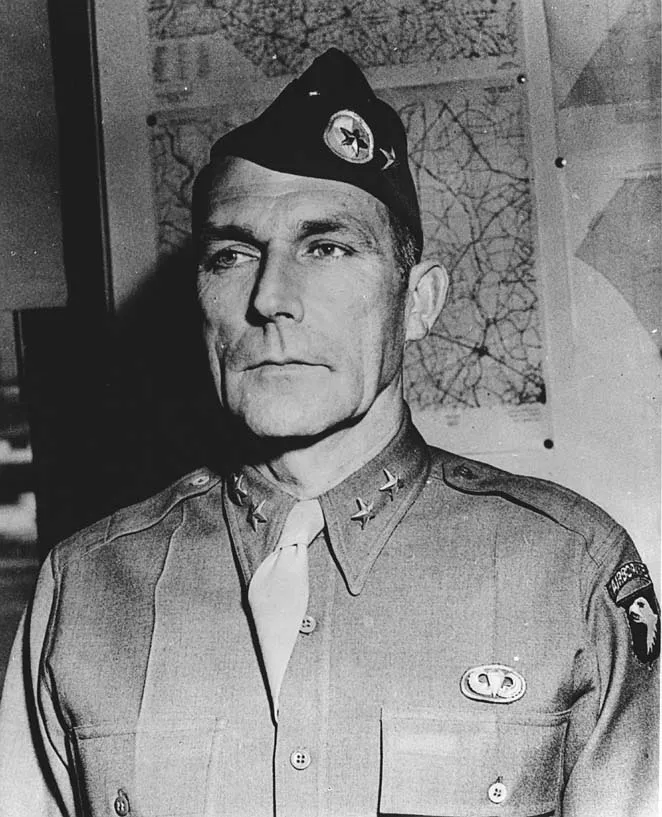

Maj. Gen. William Carey Lee, more commonly known as “Bill Lee” or just plain “Bill” to his friends, was the first divisional commander of the 101st Airborne. A World War I veteran and native of Dunn, North Carolina, General Lee was a pioneer in organizing the first U.S. Army parachute formations as well as in writing their doctrine and tables of organization. A strict but well-respected commander, Bill Lee led the division through training and into England for invasion preparation. Sadly, he was forced to relinquish command a few months before D-Day due to a heart ailment. U.S. Army

The 101st moved its headquarters to Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, and the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), sent up from Ft. Benning, became the original parachute infantry regiment in that division. New 101st units that came from the split with the 82nd Division were numbered slightly higher than their sister units in the 82nd. For instance, the 82nd included the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment (GIR), 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion (AEB), and 80th Airborne Antiaircraft/Antitank Battalion (AA/AT), while the 101st had the 327th GIR, 326th AEB, and 81st Airborne AA/AT. Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Weisberg conceived, wrote, experimented with, and developed doctrine for the deployment of parachute field artillery with his 377th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion (PFAB). Gliderborne artillery units were also forming, including the 321st Glider Field Artillery Battalion (GFAB), and 907th GFAB.

All glider-borne personnel, whether infantry, medics, engineers, or artillerymen, were not initially “volunteers” as such; the army could order a soldier to enter a glider as surely as any other vehicle, such as a jeep or a truck. And while glider riders suffered a lot of casualties from bad landings and more serious mishaps, they were not entitled to receive hazardous duty pay. To further aggravate the situation, parachutists within the same division treated glider troops with disdain, and many fights erupted from the inevitable resentment. Glider-borne personnel were required to wear old-fashioned ankle gaiters with their low shoes, while paratroopers received tall jump boots with capped toes and high ankles, taking twelve eyelets to lace them up.

The jumpers were also held to more rigorous physical training involving thousands of push-ups, long-distance runs, and speed hikes covering extreme distances in incredibly short times. So, on another level, the daredevil volunteer parachutists felt entitled to scorn all soldiers they considered to be of lesser condition, courage, and motivation. Unfortunately, glider-borne troops also fell into this category. Not until the jumpers saw countless gliders smashed into hedgerows in Normandy, with their fragile human cargoes impaled and mangled, did the paratroopers’ disdain for glider troopers stop. The situation was eventually mitigated after hazardous duty pay was approved for these brave soldiers and a special badge was devised to recognize glider training and combat insertion via glider.

Troopers of E/502 PIR lined up at Ft. Bragg in 1943, wearing M42 jumpsuits and overseas caps with the early blue and white Parachute Infantry patches. The patches are on the left side of the cap; until orders came down in 1944, these patches were optionally worn on either side of the flat overseas caps. After the regulations were written in 1944, all enlisted personnel were compelled to wear cap patches on the left side only, while officers wore them on the right side, so that rank insignia could be worn on the left side. Before these regulations came out, many Deuce officers wore the patch on the left side and pinned their rank insignia right through the patch. Signal Corps, Ray Hoffman collection via R. Campoy

Within the newly activated 101st Airborne Division was also a battalion of engineers, the 326th Airborne Engineer Battalion. The battalion’s Headquarters and Service (HQ/SVC) Company and companies A and B were glider-borne troops; only Company C was parachute-qualified. After Normandy, only jump-qualified personnel were accepted as replacements into the 101st division. The previously all-glider companies began receiving so many jumping replacements that they began forming a special “jump platoon” in each company. The same happened with replacements arriving into the 327th GIR after Normandy. Another glider infantry regiment, the 401st, was split into two parts, with half the personnel serving in the 82nd Airborne Division and the other half becoming the 3rd Battalion of the 327th GIR.

Prop blast party at Camp Toccoa, Georgia, late 1942. Col. Robert F. Sink, the commander of the 506th PIR, was anxious to have as many of his officers as possible “qualified” as parachutists, which required five jumps. He arranged for an Air Corps plane to drop groups of officers at Toccoa, before the majority of the 506th PIR went to qualify at the Parachute School (TPS) at Ft. Benning, Georgia. Each regiment and its independent battalions had its own uniquely designed prop blast mug, in which assorted alcoholic beverages were mixed for consumption by newly qualified paratroopers. Each individual was required to guzzle from the mug, while the onlookers chanted, “One thousand... two thousand... three thousand... four thousand,” just as a jumper would count when leaving the plane and waiting for his parachute to open. Drinking from the mug is Lt. Ed Harrell. The short officer visible over his shoulder is the 3/506 battalion commander, Lt. Col. Robert L. Wolverton (West Point 1938). Capt. Selve Matheson is fully visible, smiling, with a cigarette in his raised hand. Maj. George S. Grant, the XO (second in command) of 3/506, is next, standing with both hands at his side. Capt. Ernest LaFlamme is standing holding the glass, hand in pocket, while Lt. Robert I. Berry stands at far right. Both Lieutenant Colonel Wolverton and Major Grant were KIA immediately upon landing in Drop Zone D on D-Day night. Robert L. Wolverton collection via Lee Wolverton

The 101st also had a 326th Airborne Medical Company (AMC), consisting of division-level surgeons (all commissioned officers) as well as surgical teams to assist the doctors whenever frontline hospitals could be established. Although the 326th AMC was basically designed as a glider-borne outfit, a third of its personnel were jump-qualified in time for the Normandy Invasion. On D-Day, onethird of the 326th AMC entered Normandy by parachute, with the other two-thirds arriving in equal numbers via sea and glider. This dispersion ensured that at least some of the team members would arrive at the divisional hospital.

Meanwhile, the Parachute School (TPS) at Ft. Benning, Georgia, put volunteers through a four-week parachutist qualification course. These jump-qualified replacements were sent wherever they were needed within the rapidly expanding Airborne Command. In late 1942, many new graduates of TPS were sent to help upgrade the 502nd PIR into full regimental strength. Many others were sent to the various units of the 82nd Airborne Division, which was preparing for overseas movement by early 1943.

During that period, the 101st was completing training and participating in maneuvers and was not yet at full strength. This would be solved by attaching the 501st and 506th PIRs, but only after these independent units completed their separate training. The old 501st Battalion’s members had been so thoroughly dispersed that only several former members ever entered the ranks of the newly formed unit of the same number—Colonel Howard R. “Jumpy” Johnson’s 501st PIR.

The 501st Regiment existed at a later time, with all differe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: Training and Maneuvers

- Chapter 2: England Before D-Day

- Chapter 3: Normandy, Part I: The Invasion

- Chapter 4: Normandy, Part II: The Push Inland

- Chapter 5: England, Summer 1944

- Chapter 6: Holland, Part I: Liberation of the Corridor

- Chapter 7: Holland, Part Ii: The Island

- Chapter 8: Bastogne

- Chapter 9: Alsace-Lorraine

- Chapter 10: Berchtesgaden and the End of the War

- Appendix: Screaming Eagles World War II Artifacts

- Bibliography

- Index

- Copyright page

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access 101st Airborne by Mark Bando in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.