![]()

PART ONE

![]()

I. THE BACKGROUND

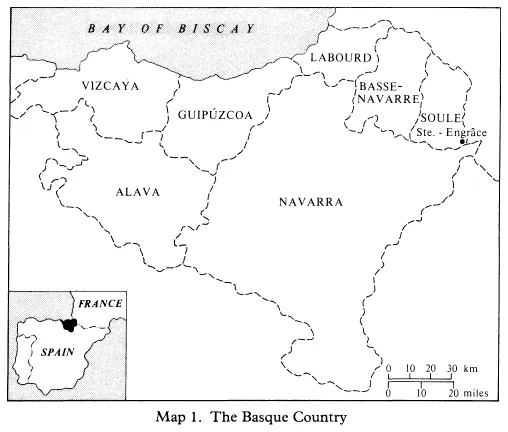

SAINTE-ENGRÂCE is a Basque mountain community located in the province of Soule on the south-eastern edge of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques. Soule (Xiberoa, or Zuberoa) is one of seven Basque provinces in Üskal-Herria, ‘the Basque Country’.1 The three northern provinces of Labourd, Basse-Navarre, and Soule are in France; the four southern Basque provinces of Navarra, Alava, Vizcaya, and Guipúzcoa lie in Spain.

Although there were well over 1,000 people in Sainte-Engrâce during the latter half of the nineteenth century, the resident population is now only 376 (see Appendix).2 The majority of the people, like their forefathers, are pastoralists who cultivate small farms scattered along the valley. Approximately 66 per cent of the adult male population are shepherds, whose daily lives are largely devoted to caring for their 4,000 sheep.3 Although most of the people are now bilingual in Basque and French, Basque is still their first and daily language. They speak the Souletine dialect, Xiberotarra, the grammar and vocabulary of which differ considerably from those of the other seven major Basque dialects.4 When spoken the Souletine dialect also has a melodic quality which the other dialects lack; and of all the Souletine Basques, the Sainte-Engrâce people have the most musical accent.

I

Although the literature about the Basques is extensive, it contains few references to Sainte-Engrâce; and these are primarily concerned with the history and architecture of its eleventh-century church. The series of articles by Foix (1921, 1922, 1923, 1924) is an exception, in as much as it provides us with some information about both the ecclesiastical and the social history of the commune.

The recorded history of Sainte-Engrâce covers a period of nearly 1,400 years, and begins with the defeat of the Franks in the seventh century. Under the leadership of Arimbert, the Frankish army invaded the Vascons of Subola (Soule) in 635. The ambush and subsequent defeat of Arimbert took place in Ehüjarre, a deep and narrow gorge which lies within the present boundaries of Sainte-Engrâce.

By the tenth century Catholicism had already been established in the community, which was known then as Urdax (or Urdaix).5 The ancient church of Sainte Madeleine, which stood on the south-eastern edge of the commune, is thought to have been built in that century. Although no visible traces of the church remain, the remnants of the Cross of Sainte Madeleine still stand on the site.

In the eleventh century the community of Urdax was renamed Sainte-Engrâce du Port, in honour of the Portuguese virgin and martyr. Variations of the name appear in the literature: Sancta Gracia in the twelfth century, Sancta Engracia in the thirteenth century, and Senta Grace Deus Ports in the fifteenth century (Cuzacq 1972: 2).

At the time of her martyrdom, Sainte Engrâce was travelling to Saragossa with eighteen of her relatives, who were also Christians. According to the legend, her breasts, liver, and heart were torn from her body; those who accompanied her were decapitated. Soon after the conversion of Constantine the Great, the city of Saragossa built a shrine in her honour.

A band of thieves pilfered the shrine in the eleventh century. In order to obtain the jewels with which the hands of the saint were laden, the thieves reportedly cut off her arm and fled to the mountains of Soule. The version of the legend commonly accepted in Sainte-Engrâce claims that the thieves hid the arm in the hollow of an oak tree beside the Fountain of the Virgin Mother at the south-eastern end of the commune. The waters of that fountain are still thought to have curative powers.

The miraculous discovery of the relic is attributed to a bull, whose horns blazed ‘like two candles on the altar’ as it knelt in front of the oak (Cuzacq 1972: 3). The relic was placed in the sacristy of the church of Sainte Madeleine, but returned time and again to the oak in which it had been discovered. This second miracle was interpreted as a sign that the saint wished for a church in her honour on that site. The new church was built in the late eleventh century or early twelfth century; and it is perhaps the finest example of roman architecture in the Basque country today.

In approximately the middle of the eleventh century, an Augustinian collegiate was founded in the community. The monastery probably served as a refuge and hostel for pilgrims travelling from Soule to Navarra. The earliest extant reference to the collegiate appears in a Charter of 1085, in which Sanche I, King of Navarra and Aragon, placed it under the suzerainty of Leyre in Navarra. Leyre was one of the most celebrated and wealthy abbeys in the Middle Ages. Although the monks of Leyre were Benedictine, the canons of Sainte-Engrâce remained Augustinian and refused to recognize the royal decree of annexation. An agreement between the two rival abbeys was reached in 1125, by which the collegiate was obliged to give Leyre two salmon once every year and two cows on Ascension and St John the Baptist.

Conflict between the abbeys resumed in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The Sainte-Engrâce canons objected to the taxes imposed upon them by Leyre; and in 1491, they were threatened with excommunication. In the fifteenth century the canons were involved in a dispute concerning pasturage rights and four cayolars of which Leyre claimed ownership (Foix 1922: 504). So far as I know, the account of this dispute is the earliest extant reference to the Souletine cayolar (olha in Basque), the pastoral institution with which a substantial part of this book will be concerned.

Following the usurpation of Haute-Navarre by Ferdinand the Catholic in 1512, relations between Leyre and the collegiate were probably severed. The collegiate was temporarily disbanded at the end of the sixteenth century, when its canonates were allocated to priests in other parts of Soule.

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, Sainte-Engrâce was one of six royal boroughs. One of the most important documents in the history of the commune was drawn up in that century—namely, the Coutume de Soule. During the reign of François I and under the direction of the jurist Jean Dibarrola, a general assembly of Souletine nobles and clergy was convened in 1520. The purpose of the assembly was to codify the customary laws and privileges of the province. Sainte-Engrâce was represented by one of its canons (Nussy Saint-Saëns 1955: 35). The Coutume covered several different aspects of Souletine law; but a substantial portion of it was devoted to ‘the right of the cayolar’.

The Coutume was first written in Gascon, the official administrative language of the period. For this reason, the Gascon term cayolar—rather than its Basque equivalent olha—is employed in the text. Etymologically cayolar is derived from another Gascon word, couye, meaning ‘ewe’ (Lefebvre 1933: 192). As defined by the Coutume, the cayolar is a pastoral syndicate which consists of a group of shepherds, their communal herding hut, corral, and the mountain pastures on which their flocks graze during the months of summer transhumance.

The ‘law of the cayolar’ decreed that the members of each pastoral group should live ‘socialement’ in the hut, and that their primary duties were to tend their communal flocks and to make cheese from the milk of the ewes (Lefebvre 1933: 192). The emphasis placed upon the cohabitation of the shepherds ‘socialement’ is especially interesting, because it continues to receive expression in the present olha groups of Sainte-Engrâce. (See Chapter IX.)

The ‘right of the cayolar’ defined in the Coutume provides my account of the modern olha with an historical depth of more than 400 years. The ‘right’ was threefold: the right of pasturage on a specified tract of mountain land was reserved exclusively for the members of the pastoral group; the cayolar was granted ownership rights to the hut, the corral, and the land on which these stood; and thirdly, the members of the cayolar received the right to use timber from the nearby forests for firewood and for the construction and repairs of the hut and corral (Nussy Saint-Saëns 1955: 89). These rights are still accorded to the Sainte-Engrâce shepherds by the commune.

Shortly after the Coutume de Soule was written, the Protestant forces of Jeanne d’Albret invaded Catholic Soule. In 1570 the Sainte-Engrâce church was burned by the Huguenot army of Montgomery. Although the archives, interior, and ornaments of the church were destroyed, the walls remained intact. The relic of the saint is said to have been surrendered to the enemy by one of the local priests (Foix 1923: 80).

In order to punish the Sainte-Engrâce people for having refused to embrace Protestantism, Jeanne D’Albret gave a large tract of their communal forest and pasturage to the neighbouring Béarnais communes of Lannes, Aramits, and Arette. Nearly 300 years later, in 1866, the Sainte-Engrâce people contested the legitimacy of her action in the Court of Appeal at Pau and demanded that the land should be returned to them. The court rejected their claims; and some of the people are still obliged to pay the Béarnais communes for the use of those pastures.

When Arnaud II de Maytie became Bishop of Oloron in 1622, the collegiate of Sainte-Engrâce was re-established; and two of its priests were sent to Saragossa to obtain a new relic of the saint. This relic, the third finger of her right hand, is now kept in the sacristy of the church.

In the eighteenth century local attempts to preserve the autonomy and independence of the collegiate suffered further defeat. In the first quarter of that century the Bishop of Oloron received royal authorization to annex the collegiate, and thereby to increase the revenue for his newly founded seminary (Foix 1923: 83). The bishop promised that two places in the seminary would be reserved each year for Souletine students; and that special preference would be given to candidates from Sainte-Engrâce. The three priests and the priest-sacristan of the commune opposed the annexation; and the case was taken to the Council of State. In 1725 Louis XV supported the Bishop of Oloron, and the decree of union was re-confirmed (Foix 1923: 85).

During the Reign of Terror, many of the Souletine clergy escaped to Spain; but the priest and vicar of Sainte-Engrâce steadfastly remained in their mountain cul-de-sac. The Sacraments were administered covertly in the grange of the former presbytery (Cuzacq 1972: 11). In order to conceal his true profession, the vicar is reported to have enlisted himself as a mule-driver in a military caravan. His expertise in deceiving the authorities was further demonstrated when customs officers were sent to the commune. According to local tradition, Haritchabalet played a vital role in the flourishing contraband trade by staging mock funeral processions. The coffin was filled with smuggled goods; and while the officers knelt to express their respect, the coffin was transported safely past them.

During the career of Haritchabalet, the customs officers received their board and lodging in local houses. In 1840 his successor convinced the municipal council that the officers should be provided with their own station—ostensibly to control the contraband trade more effectively. But his primary objective was to check the reported promiscuous behaviour of the young officers.

In 1838 the Syndicate of Soule was established by royal decree with a view to regulating the exploitation of natural resources in the province, and to promote the growth of the Souletine economy. In keeping with its previous attempts to remain independent, Sainte-Engrâce was one of only two communes which refused to join. By doing so the community retained possession of its forests, mountain pasturage, and common lands, which otherwise would have become the communal property of the Syndicate.

In 1841 the church was classified as an historical monument; and under the direction of Etchecopar, one of the few priests whom Sainte-Engrâce has produced, the church was completely renovated between 1850 and 1864.

With the exceptions of Haristoy (1893) and Foix (1921, 1922, 1923, 1924) the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century references to Sainte-Engrâce contain little material of sociological interest. Haristoy gives us a fairly detailed account of the procession to the Three Crosses at Lechartzu, a col located on the north-western edge of the commune, on Corpus Christi; and he makes the interesting observation that the processional cross was carried à tour de rôle by the men whose lands were traversed by the pilgrims.6 People who participated in the procession before the Second World War confirmed his report in 1976/7.

II

It is outside the specific aims of this book to explore fully the recent history of Sainte-Engrâce, which, in the French Basque country, is widely regarded as the most geographically and socially isolated community in the region; but it is important to the achievement of certain aims to examine selectively events which have brought the Sainte-Engrâce people into contact with the outside world during the latter part of the nineteenth century and until 1979. In this way it will be possible to appreciate the extent to which the people have been exposed to outside influences and yet have retained many aspects of traditional Basque culture which have been lost or are becoming obsolete in other parts of the Basque country.

During the nineteenth century and until the 1920s the period of summer transhumance brought the Sainte-Engrâce men into close contact with three groups of outsiders: the shepherds from lowland Souletine villages whose households owned shares in herding huts located on the mountain pastures of Sainte-Engrâce and who spent the milking and cheese-making season in these huts; Spanish Basque shepherds from Isaba, the village in north-eastern Navarra that is closest to Sainte-Engrâce; and shepherds from southern Navarra who travelled with their flocks to the mountain pastures bordering the southern edge of Sainte-Engrâce.

Formerly, the Isaba and southern Navarrese shepherds regularly hired Sainte-Engrâce men to milk their ewes and to make cheese for them in June and July. According to the Sainte-Engrâce men, they and their forefathers were hired to perform these tasks because they were widely acclaimed to be the most skilful shepherds and cheese-makers in the region. During the two-month period the Sainte-Engrâce men lived in huts owned by Isaba shepherds and which lay between five and fifteen kilometres south of the commune. Those who were hired were generally young, unmarried men whose fathers and/or brothers remained in Sainte-Engrâce to act as shepherds for their own households. The Sainte-Engrâce men continued to work for Isaba shepherds until about 1927, by which time few of the large Isaba flocks remained intact and, according to the Sainte-Engrâce men, when ‘the Isaba shepherds lost interest in the arts of cheese-making and shepherding’.

During the months of summer transhumance, the Isaba and lowland Souletine shepherds occasionally came down from the mountains to drink in Sainte-Engrâce cafés; and some were regular visitors in local households. I am told that conversations between the Isaba shepherds and the people were generally conducted in Basque, though the two groups had difficulty in understanding their respective dialects.

In the nineteenth century and until 1913, the Sainte-Engrâce people were also well known among the merchants and traders of Isaba, which was formerly regarded as ‘the first neighbour village’ (herri-aizoa) of Sainte-Engrâce. In this part of the Basque country, a community has only one ‘first neighbour village’, with which a trading relationship is established. Some of the elderly people vividly recalled having made the thirty-five-kilometre journey to Isaba on foot or on mule when they had livestock, cheese, and woollen cloth to sell or to trade in return for goods such as salt, sugar, cotton cloth, and metal tools.

When the paved road from lowland Soule to the north-western end of the commune was completed in 1913, Tardets became the ‘first neighbour village’ of Sainte-Engrâce. As a result, commercial ties between Sainte-Engrâce households and traders from Isaba and other nearby Navarrese villages were weakened; but they were by no means severed, for the Sainte-Engrâce shepherds continued to rely upon certain traders to supply them with contraband goods such as wine and spirits. A fairly large-scale contraband trade flourished in the area until the Second World War.

Before the completion of the road, Sainte-Engrâce was accessible to lowland Soule only by means of narrow, rough trails. The few French Basques who were not shepherds and who travelled to Sainte-Engrâce regularly were mostly priests and bishops. Pub...