![]()

CHAPTER 1

“Silencing” Memories

Why Are We Again Forgetting the No Gun Ri Story?

On September 29, 1999, with the comment “It was a story no one wanted to hear,” the Associated Press (AP) brought an uneasy flashback of the Korean War to the American public’s mind. Along with an in-depth analysis of declassified military records, the AP had interviewed dozens of Korean War veterans and No Gun Ri survivors by telephone and in person.1 The long-submerged memories that had lasted nearly a human life span were fatigued, splintery, and malleable to reconstruction. Rather than claiming demonstrative truth, the Associated Press cautiously unfolded a horrific scene from a long-forgotten war: “American veterans of the Korean War say that in late July 1950, in the conflict’s first desperate weeks, U.S. troops killed a large number of South Korean refugees, many of them women and children, trapped beneath a bridge at a hamlet called No Gun Ri. …What then happened under the concrete bridge cannot be reconstructed in full detail.”2

The next day, the AP’s account of the No Gun Ri incident appeared across the U.S. media, with many newspapers carrying an abbreviated version. Prestigious newspapers, including the New York Times and the Washington Post, gave special attention to the story by devoting a portion of their front pages to it. The New York Times published a picture of an elderly Asian woman standing in front of a bridge with a sullen expression, making a somewhat intense gesture. The caption ran: “Chun Choon Ja, a survivor, during a commemoration last year at the bridge near No Gun Ri.” This enigmatic image of a Korean woman conjured the disturbing scene that had been forgotten for five decades. Considering the passage of time, the report was somewhat terse, and thus immediately raised a chain of questions: Why were we hearing the story now? How had the AP found this forgotten story? What caused such a tragic incident? How could we possibly know the details of incidents that took place five decades ago?

This special AP report was initiated by testimonies of the No Gun Ri survivors who had held on to their memories for those five decades. Under the authoritarian rule of the U.S.-allied South Korean government, however, survivors and victims’ relatives were afraid to share their traumatic stories because they might be accused of being communist sympathizers. Nevertheless, Chung Eun-Yong, who lost his five-year-old son, Goo-Phil, and two-year-old daughter, Goo-Hi, had devoted his life to bringing public attention to this forgotten episode. He had collected all available archives related to the incident and in 1994 published a novel titled Do You Know Our Pain?3 and based on the story told by the survivors. Moreover, he had sent petitions seeking compensation for the survivors and the victims’ families to both the U.S. and the Korean governments. Even so, Chung’s family and the No Gun Ri villagers found it difficult to find a media outlet; their files were rejected by both the South Korean and the U.S. governments. In the 1990s, when South Korea began to have a liberalized political atmosphere, a few Korean media reported the No Gun Ri incident, but it had little impact on the public’s consciousness at that time.4 This event did not receive international recognition until investigative reporters from the Associated Press brought it to the American public in 1999.

Many newspaper articles drew an analogy between the No Gun Ri incident and the 1969 My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War.5 Both were U.S. atrocities involving foreign civilians; both would be “hard-sell” stories in the U.S. media.6 In an intriguing difference, however, My Lai was told through pictures, whereas No Gun Ri was recalled through oral testimonies. The report of the My Lai massacre appeared with an emotion-provoking image that depicted the dead bodies of children and women,7 whereas the coverage of the No Gun Ri incident had no similar eyewitness photo that could play “the primary role of convincing disbelieving publics about the atrocities.”8 Although the bullet-riddled bridge and the survivors’ wounded bodies provocatively evoked tragic memories, they became visual evidence only when supported by verbal testimony. The backbone of the story thus became the testimony emerging from numerous memory sites, including official archives, evidence collected at the scene, the faltering voices of GIs,9 and survivors’ memories etched in their wounded bodies and minds.

Such eclectic utterances substantially validated the No Gun Ri story to the point that the AP investigative reporters—Sang-Hun Choe, Charles Hanley, Martha Mendoza, and Randy Herschaft—won two of journalism’s most prestigious awards in 1999 and 2000: the Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting and the George Polk Award for international reporting. Furthermore, influential media institutions’ competitive coverage, along with substantial evidence, provoked the Pentagon to order an official investigation of the incident. After one year, however, Secretary of Defense William Cohen announced that a “thorough and exhaustive review”10 by the U.S. Army was not able to uncover what had really occurred at No Gun Ri. Neither specific casualty figures nor the existence of orders to shoot could be clarified by their inquiry. Confirming the army’s account, the Clinton administration, while officially acknowledging the American troops’ killing of the innocent civilians, nevertheless called for a didactic closure by suggesting how the incident should be remembered: “As we honor those civilians who fell victim to this conflict, let us not forget that pain is not the only legacy of the Korean War. American and Korean veterans fought shoulder to shoulder in the harshest of conditions for the cause of freedom, and they prevailed. The vibrancy of democracy in the Republic of Korea, the strong alliance between our two peoples today is a testament to the sacrifices made by both of our nations 50 years ago.”11

The official closure of the No Gun Ri investigation asked ex-GIs to bury their traumatic memories under the shining narrative of a noble mission while encouraging victims to ease their bitterness through gratitude for their country’s prosperity. The U.S. government decided not to give a formal apology to the South Korean people, nor would it offer financial compensation to the victims’ families. In fact, Clinton’s statement used the word “regret,” as opposed to “apology,” a choice that provoked great resistance among South Korean survivors and victims’ relatives.

We know that word choice shapes power relations in symbolic interaction. As Erving Goffman puts it, “apology” invites the offended party to say whether the “remedial message” has been received or is sufficient.12 Through the word “regret,” however, Clinton’s statement diminished survivors’ potential role in responding to an “apology.” In fact, South Korean survivors’ calling the U.S. Army report a “whitewash” became a faint echo that barely resonated with the public. After the U.S. media closed the No Gun Ri story, the British Broadcasting Corporation produced a compelling documentary, Kill ’Em All (2001), that showed how the official U.S. investigation may have manipulated testimonies and archives to gloss over facts about the incident. On April 14, 2007, six years after Clinton’s statement, the Associated Press again revealed that during the 2001 investigation the U.S. Army dismissed a letter from the U.S. ambassador in South Korea in 1950 that proved that the U.S. military had a policy of shooting approaching refugees during the Korean War. Nonetheless, this counter-voice did not last long in the U.S. media. The evidence of the No Gun Ri story quickly melted into the amnesia that is the American collective memory of the Korean War.

The purpose of my research is to analyze this trajectory of the No Gun Ri story from forgetting to remembering to forgetting again. This research has not attempted to draw detailed pictures of what really happened at No Gun Ri at the end of July 1950, a task that I believe to be impossible. Neither does it look at how meticulously the media have portrayed the incident. My research has not focused on “truth claims” themselves, but rather on narratives that are “the grammar of truth claims.” This approach came from the realization that the media’s constructed narratives often appear as accounts of “what the event actually was” as opposed to “what it might be.” The media’s accounts, often with no reflexivity, can easily create a situation that discourages the public from being critical appreciators of historical texts. Thus, this analysis of media texts could be completed only when it was accompanied by a comparative study of both texts: those onstage (the media texts) and those backstage (the primary sources). This realization encouraged me to look into survivors’ accounts—the critical sources “standing” backstage behind the media texts of the No Gun Ri incident.

To get an account of survivors’ testimonies and to compare them with the narratives in the media coverage, I conducted oral history interviews with twelve survivors and victims’ relatives during the summer of 2005 at three sites in South Korea: Youngdong County, Taejeon City, and Seoul. The narrators13 were selected because their testimonies were the primary ones used in the U.S. media coverage of the incident. The techniques of the oral history interview have developed among oral historians as a means of allowing voiceless people to tell their stories in their own words. Barbara Allen, an oral historian, points out that the terms “researcher” and “narrator” are more appropriately used in connection with the oral history interview, as opposed to the terms “interviewer” and “interviewee,” which connote “doer” and “doee.”14 Taking Allen’s suggestion, I refer to myself as the “researcher” and to the survivors and victims’ relatives of the No Gun Ri incident as the “narrators” throughout this essay.

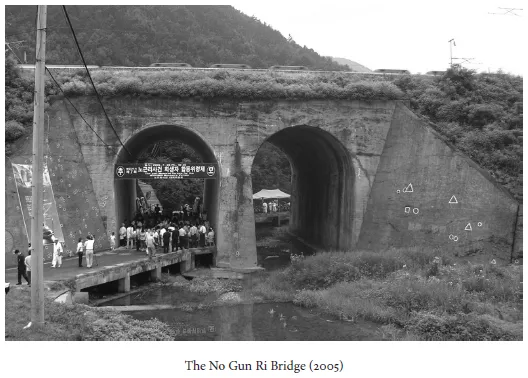

Although I met narrators more than five decades after the incident and after the U.S. Army had ended its investigation, their emotions had persisted so strongly that they vividly shared their memories. Even now, the bridge under which U.S. soldiers attacked these civilians functions as a viaduct of the railroad system. The bridge’s presence, with its many bullet holes, has served as a mnemonic object, continuously inviting villagers to share their memories. Moreover, many of the survivors and victims’ relatives still live in the same or nearby villages. Within this geographical cluster in rural South Korea, a relatively strong kinship remains that contributes to the maintenance of a solid collective memory. Survivors’ memories allowed me not only to showcase the subversive attributes of survivors’ testimonies in reconstructing a past event, but also to deepen my dissection of media texts by revealing the ways in which the media selectively highlighted as well as ignored survivors’ testimonies in the process of forming narratives.

NARRATIVIZING, HEGEMONY, AND COLLECTIVE AMNESIA

Memory scholars have recognized collective memory as an active site where heterogeneous meanings, identities, and powers compete for hegemony. Memory studies have developed by identifying as well as analyzing varying degrees of discrete tensions that arise in memory construction, including tension between collective and individual memories, official (national) and vernacular (local) memories, images and words, written memories and oral testimonies, and ultimately the past and the present.15 Tensions arising in memory construction invite struggling, negotiation, and ultimately manufacturing of an illusory consensus, what Gramsci calls the state of hegemony.16

Consensus in memory construction appears as a set of narratives. Maurice Halbwachs notes that the act of remembering is inevitably tamed by our “habit of recalling them [past events] in organized sets.”17 Past events are perceived as narratives that memory continuously remolds. Using a compelling metaphor, David Lowenthal suggests that our country (the present) has attempted to colonize the foreign country (the past) by reorganizing its events with contrived narratives. It is narrativizing that transforms the past events (mysterious, anomalous, and constantly changing texts) into the perceived events (palpable, shaped, and static texts). Furthermore, narratives are functional devices through which past events are efficiently politicized to accommodate power relations in the present.18 As John Bodnar notes, narratives are not merely “structures of meaning” but also “structures of power,”19 whose formations skillfully navigate the act of remembering, a process of generating the narrative in hegemony as opposed to a narrative among many.

Narrativizing in collective memory is unique because it takes place in two domains—forgetting and remembering—both of which take place simultaneously as “co-constitutive processes.”20 Narratives are often constructed in such a way as to naturalize the arbitrary selection of memories: what to forget and what to remember. Forgetting is an indispensable act to the creation of hegemony, because it is used to exclude counter-evidences whose very presence contests narratives that have been shaped by the reigning power relation. Such a willful forgetfulness in the act of remembering has been called by different names: concerted forgetting, organized oblivion, and collective amnesia.21

Collective amnesia is particularly germane to war. Wars in American collective memory are remembered in terms of the rhetoric of heroism, stories that cherish the virtues of intrepidity, progress, and victory.22 Within the narrative of triumph, military activities are often romanticized as patriotic, altruistic, and purely self-determined actions. Inhumanity does not appear as an inherent characteristic of war, but is considered as either the evidence of the enemy’s immorality or an anecdotal tragedy that asks to be forgotten.

More than any other, the Korean War is exemplary in that its theme is largely shaped by the act of forgetting. Its official narrative—America’s mission of saving South Korea from merciless Communist aggression—has maintained an absolute hegemonic power through forgetting a substantial body of counter-memories that historians and journalists have cultivated since the war broke out. One such counter-memory is the depiction of South Korean police atrocities toward civilians.23 Another counter-memory is offered by historians who resist the reductive views of the war’s cause by arguing that although international power relations aggravated the conflicts on the Korean Peninsula, the fundamental cause of the war resided within the local context of class conflicts resulting from Japanese colonialism.24

A more thorny issue among historians is America’s role on the Korean Peninsula before and during the war. In 1945, when the Japanese colonial power withdrew from the peninsula, the Soviet Union and the United States, the winners of World War II, divided the Korean Peninsula along the 38th parallel and began to take on separate trusteeship of North Korea and South Korea. A number of historians have offered critiques suggesting that U.S. trustees increased domestic tension by accusing many Korean citizens of being Communist sympathizers. Ironically, the U.S. trusteeship, whose objective was to secure an ultimate liberation of South Korea, blocked many legitimate voices and actions that aspired to extirpate the legacy of Japanese colonial rule.25 Worse, U.S. trusteeship favored conservative groups of landlords and businessmen, and even restored power to some former officers who persecuted their own fellow citizens during Japanese occupation. As Carter Eckert and his associates put it, “Unfortunately, what seemed middle-class and democratic by American standards was more often than not upper class, reactionary, and collaborationist by Korean standards in 1945.”26

These counter-arguments, put forth by historians and news correspondents, seldom have entered American public memory of the Korean War. Public memory does not often contest the official narrative of the war: Communist atrocities as the cause and the valor of America’s efforts to rescue an endangered Korean Peninsula as the response. This narrative always has been manifested in U.S. public memory as a dogmatic truth, but never appeared as one of many plausible, yet unconfirmed narratives. As Paul Pierpaoli puts it, the rigid mentality of 1950s McCarthyism highly politicized the Korean War “in a most peculiar and destructive way.”27

In this barren landscape of Korean War memory, the U.S. media’s introduction of the No Gun Ri incident—atrocities by American soldiers—seemed to shock historians, since “there was no previous report of any atrocity of this magnitude by United States forces in the Korean War.”28 The abrupt emergence of the No Gun Ri accounts in the U.S. media at the end of the 1990s may have reflected the evolving contexts of the memory of the war: the end of the Cold War era, the newly unearthed archives from the former Soviet bloc, and the end of these witnesses’ life spans. In fact, many Korean War veterans’ voices have been introduced recently in books such as I Remember Korea (2003) and Voices from the Korean War (2004). It is important to examine whether these newly unearthed memories have functioned to trigger counter-narratives or to reinforce official narratives. As a critical witness of the evolving milieu of the Korean War, my research identifies four narratives emerging from the No Gun Ri text and examines whether each narrative enhances or counters the official a...