![]()

1. Foreword

Some 10,000 years ago, a handful of animal species were first incorporated within the human habitat on a permanent basis. Their reproduction and well-being became directly dependent on their keepers. As domestication progressed, physical proximity became a mutual source of infectious disease and traumatic injuries for humans and animals alike. New zoonoses developed, “diseases and infections which are naturally transmitted between vertebrate animals and man” (Shakespeare 2002, 1). An evident example of such diseases is rabies, known to spread through dog bites to other animals and humans. This disease was described as early as the 13th century by, among others, Albertus Magnus (Walker-Meikle 2012, 47). The written record provides accounts of other epidemics threatening livestock as well as humans. A dramatic woodcut in the 1532 German edition of Francesco Petrarch’s 1492 De remediis utriusque fortunae (Medicine Against Both Fortunes II) shows a tumultuous plague scene in which victims not only include people, but also a horse, a dog, a cat, a rooster, and even a perching bird (Figure 1). Recent outbreaks of epidemics in Europe, such as blue tongue in the summer of 2006, as well as foot and mouth and BSE in cattle, sheep and pigs have directed attention to the dramatic impact of modern zoonoses on human and animal populations (Vann and Thomas 2006). During 2010, the so-called ‘pig flu’ (H1N1 virus), yet another animal-related pandemic, directed attention to the inseparable nature of human and animal welfare. While the complexities of public health phenomena are far too subtle to be characterized using the patchwork of methodologies still being developed for the archaeological evaluation of animal bones, these epidemics clearly illustrate the large extent to which the health of people and animals have become intertwined throughout history (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Plague scene in the 1532 German edition of Petrarch’s book

Figure 2. Stray pig scavenging on an urban dump near Agra, India

It is however, not only epidemics, usually elusive from an archaeological point of view, that have emerged as people and animals have co-existed. In addition to physical closeness, modes of animal keeping and exploitation have continuously resulted in non-infectious diseases whose treatment or neglect can be recognized on the skeleton of ancient animals. Such phenomena not only reflect the health condition of livestock, but are characteristic of cultural attitudes towards animals. The slogan attributed to the 1904 Nobel Prize laureate Ivan Petrovich Pavlov: “Doctors treat people, veterinarians – humanity”, is as relevant in our modern society as has been the special attention devoted to emotionally significant and/or valuable animals in the past.

Traditional animal palaeopathology was rooted in palaeontology, with little or no interest in the cultural aspects of animal disease. Animal remains recovered from archaeological deposits, however, are bona fide archaeological artefacts: they represent the cumulative effects of human decisions that in ‘man-made’ domesticates include choices made during an animal’s life including selective breeding and the treatment of disease. Implicit to the concept of this book is, therefore, the hypothesis that most pathological deformations in archaeozoological specimens were brought about by conscious or inadvertent human influence.

Wild animals appear at first glance rather peripheral to the archaeological study of animal disease. Once domestic animals appeared they provided the majority of meat for their human keepers and thus soon became the dominant component in archaeological bone assemblages. The statistical probability of finding odd pathological specimens among the few wild animal remains therefore radically decreased. In addition, aside from hunting injuries, only a relatively limited range of diseases affect the skeletons of game: natural selection rarely allowed the development of chronic conditions seen in domestic animals. It is this contrast however, that offers a new perspective in the palaeopathological study of wild animal remains.

As will be shown in the chapters to follow, a combination of emotion, knowledge and social communication can sometimes be clearly glimpsed behind the dry osteological evidence of animal morbidity from archaeological deposits. Given our recent cultural heritage there is sometimes a tendency to try and separate sacred and profane activities. Some forms of behaviour related to animals, healthy as well as diseased, were related to traditional ideologies embedded in ancient societies (Insoll 2004, 11–12). Special aspects of culture are reflected in the treatment of diseased or injured animals. This is especially important, because animals often incorporate powerful symbolic roles. One of the most convincing current examples is the treatment of elephants wounded by land mines in the Elephant Hospital run by the NGO ‘Friends of the Asian Elephant’ in Hangchatr District, Lampang, Thailand. Among the wide range of ordinary elephant diseases cured there, the humanitarian aspect of rehabilitating land mine victims carries a valuable ethical message that adds a new dimension to Pavlov’s bon mot (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Baby Mosha was injured by a landmine when she was only seven months old back in 2006. She has fully recovered using a prosthetic limb (FAE)

![]()

2. Introduction

This book is a review of zoological remains affected by disease and trauma recovered from archaeological deposits. The justification for the study of this special aspect of animal palaeopathology is twofold:

• Knowledge of diseases in ancient animal populations can help in elucidating archaeological and historical trends in herding, animal welfare and attitudes toward animals.

• Information on pathological processes from any time period contributes to the overall body of veterinary knowledge, giving some conditions – otherwise unavailable to modern-day veterinarians – a longer time depth.

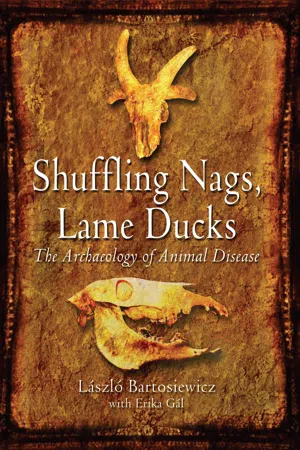

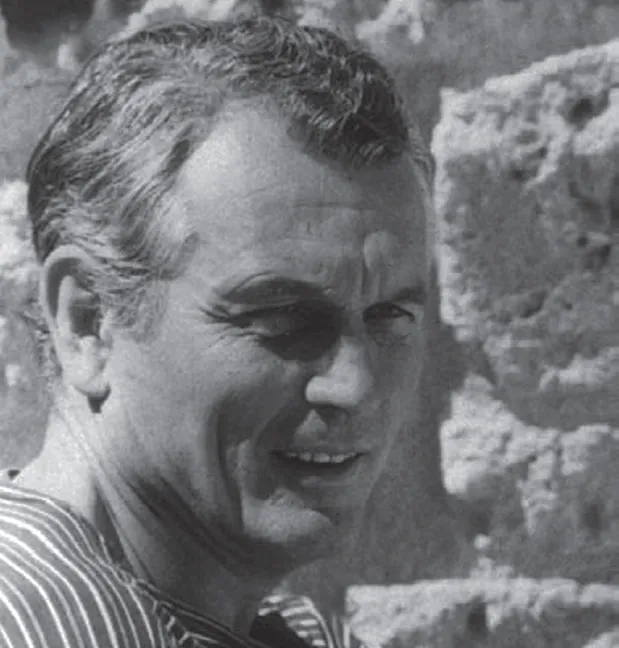

For over two generations, pathological phenomena observed on animal remains have been described in individual site reports by many faunal analysts publishing together with excavating archaeologists. Such information, however, has often remained hidden as isolated curiosities in publications that were hard to come by. By the 1970s, reviews of pathological cases in archaeozoology began to appear (e.g. Haimovici and Hrisanidi 1969; Harcourt 1971; von den Driesch 1975; Siegel 1976; Van Wijngaarden-Bakker and Krauwer 1979). In her dissertation, Wäsle (1976) summarized information on animal morbidity from a great number of the archaeological site reports available at the time. During this time, Sándor Bökönyi (1926–1994; Figure 4), founder of institutionalized archaeozoology in Hungary (Bartosiewicz and Choyke 2002), considered contributing to the increasingly vivid discussion by synthesizing observations made on data he had recorded from archaeological sites in Hungary. Following the 1980 publication of John Baker and Don Brothwell’s (Figure 5) seminal volume Animal Diseases in Archaeology, however, the market would have been unlikely to accommodate two books on the same specialist topic, which was still narrowly defined at the time. He therefore abandoned plans to publish a book on his collection of pathologically modified bones.

The core of information compiled by Bökönyi included 52 unpublished bone specimens and 183 drawings and photographs of varying quality kept in the Archaeological Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (HAS). These numbers may look unimpressive considering the tens of thousands of ‘ordinary’ animal bones recovered from some excavations. Following Bökönyi’s untimely death in 1994, however, data gathering continued and the number of cases available for study multiplied. In spite of the notorious rarity of pathological specimens, this material began forming a sound basis for a new summary. In addition, in-depth research into the already existing archaeozoological literature has also become inevitable. Only following such preparations could the review and analysis of the material be attempted.

Critics of this book will probably note that there has been a heavy emphasis on descriptive, macromorphological methods throughout the volume. Until recently, even in more advanced human palaeopathology, it has been, at most, radiography which tended to be used, rather than more invasive and relatively time-consuming histological techniques (Bell 1990, 85). The most sophisticated research methods have only been applied experimentally in the palaeopathological study of animals.

This volume, however, will probably be the last book dealing exclusively with animal palaeopathology in the methodological terms that prevailed during the second half of the 20th century. There have been real advances as broad ranges of histological, radiographic, immunological, molecular genetic, etc, data are gradually integrated into macromorphological descriptions. It is through these additions that our understanding of ancient animal disease and its cultural interpretation will be further improved.

Summation

Throughout this book constant references will be made to Baker and Brothwell’s (1980) ground-breaking work Animal Diseases in Archaeology, the first and only handbook devoted to the palaeopathology of archaeological animal remains published to date. Their book was never intended to be a diagnostic reference catalogue, although it has been used as such by many in the absence of other relevant information (Thomas and Mainland 2005, 2). Focusing on individual finds, however, not only falls short of integrating pathological information within a broader archaeozoological context, but also diverts attention from its cultural relevance. A diagnosis-centric approach has remained a nearly inevitable form of technical bias in animal palaeopathology. It should be replaced with the “conservative application of identification and quantification procedures” (Reitz and Wing 1999, 238) in zooarchaeology, which will always remain fundamental in inductive research using databases indispensable to understanding what lies behind a particular pathological phenomenon.

![]()

3. Basic concepts

The ornithologist, physician, and army officer Robert Wilson Schufeldt has been credited with having introduced the term palaeopathology from the Ancient Greek words palaios (ancient) and pathos (suffering) in volume 2 of the Standard Dictionary in 1885. The concept was consolidated by Sir Marc Armand Ruffer in 1913 (Marí i Balcells 2004, 129). While its complex, multidisciplinary vocabulary (derived from palaeontology, archaeology as well as medical and veterinary science) cannot be explained here in full detail, some relevant terms need to be discussed briefly. A special effort has been made to simplify jargon while providing scientific equivalents in Latin wherever the use of vernacular terms would have caused ambiguity. A small glossary at the end of the book contains less frequently used miscellaneous technical terms that may aid in orienting the non-specialist reader.

Widespread and specious arguments surrounding the correct usage of two closely related terms: ‘archaeozoology’ or ‘zooarchaeology’ have abounded in the literature since the late 1970s (for a most balanced recent summary see Reitz and Wing 1999, 3). By now both terms have come to mean the analysis of animal remains from archaeological sites. The hierarchical classification by Bobrowsky (1982, 181, fig. 1) suggests that zooarchaeology is applied archaeozoology with an archaeological emphasis. I would rather stress the parallel development of the two concepts as the source of difference (Bartosiewicz 2001): while in Eurasia archaeozoology is often practiced as a form of applied zoology, zooarchaeology in the New World and most...