eBook - ePub

Why Not the Best?

The First Fifty Years

Jimmy Carter

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Why Not the Best?

The First Fifty Years

Jimmy Carter

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Why Not the Best?, originally published in 1975, is President Carter's presidential campaign autobiography, the book that introduced the world to Georgia governor Jimmy Carter and asked the American people to demand the best and highest standards of excellence from our government.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Why Not the Best? an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Why Not the Best? by Jimmy Carter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

TWO

Farm

My life on the farm during the Great Depression more nearly resembled farm life of fully two thousand years ago than farm life today.

I have reflected on it often since that time; social eras change at their own curious pace, depending on geography and technology and a host of other factors. It is incredible with what speed these changes have totally transformed both the farming methods and the very lifestyle I knew in my boyhood.

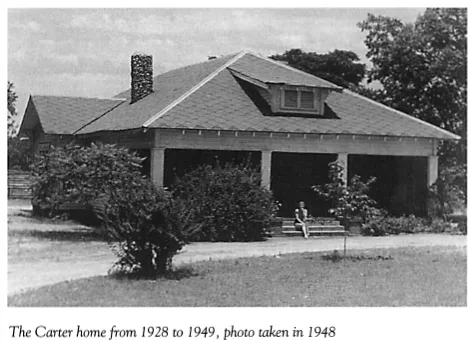

We lived in a wooden clapboard house alongside the dirt road which led from Savannah to Columbus, Georgia, a house cool in the summer and cold in the winter. It was heated by fireplaces within two double chimneys, and by the wood stove in the kitchen. There was no source of heat in the northeast corner room where I slept, but hot bricks and a down comforter helped to ease the initial pain of a cold bed in winter.

For years we used an outdoor privy in the back yard for sanitation and a hand pump for water supply. Later, another shallow well was dug under our back porch and a hand pump was installed there, and eventually we had a windmill and running water in our home. In the bathroom was a cold shower and a commode and lavatory; it was not unusual during the winter to find the pipes frozen and the commode pushed off the wall and lying on the floor. Water for bathing had to be heated on the wood stove.

Our yards were covered with white sand, replenished every spring from a nearby sand pit. The yards were kept clean by sweeping once or twice a week with brush brooms and, typically, were occupied by dogs, chickens, guineas, ducks, and geese.

Fried chicken and chicken pie were often part of our regular meals, and there were hen nests located in every convenient place—alongside buildings, in the forks of trees, and wherever else the hens had an inclination to lay eggs. There was no fence around our yard, and we had frequent poultry fatalities on the road in front of our house. Guineas were especially vulnerable to the passing of cars.

The dominant feature of the backyard was the woodpile with large stocks of hickory and pine for burning in the fireplaces and the cooking stove. Pecan, mulberry, chinaberry, magnolia, and fig trees gave us shade and facilities for tree houses and climbing. All in all, it seemed a comfortable and enjoyable place to live.

Our lives then were centered almost completely around our own family and our own home.

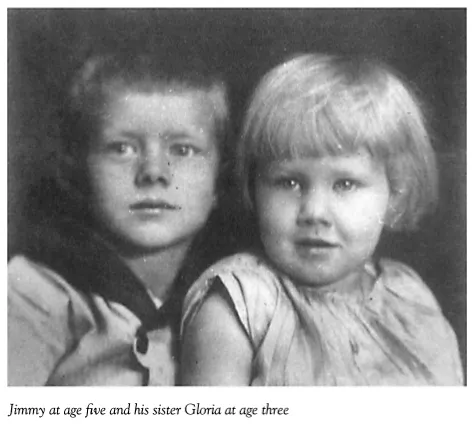

I was an only son in those early years, my brother, Billy, not being born until I was thirteen years old, and my father was a very firm but understanding director of my life and habits. In retrospect, the farm work sounds primitive and burdensome, but at the time it was an accepted farm practice, and my dad himself was an unusually hard worker. Also, he was always my best friend.

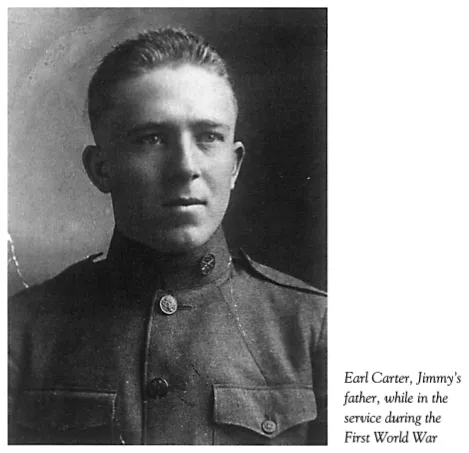

My father, Earl, was an extremely competent farmer and businessman who later developed a wide range of interests in public affairs.

He was thirty years old when I was born, stood about five feet eight inches tall and weighed 175 pounds. He was a good athlete, played baseball as a pitcher on the local town team, and was an excellent tennis player. In fact, adjacent to our house, between the house and store, we had a tennis court on our farm. There were also three other tennis courts in Plains, and with the exception of high school baseball and basketball, tennis was our most important competitive sport while I was growing up. I could do well even against older high school boys, but I could never beat my father. He had a wicked sliced ball which barely bounced at all on the relatively soft dirt court.

Daddy loved to have a good time and enjoyed parties much more than did my mother. I remember one occasion when my parents had a party at our home for doctor and nurse friends with whom my mother worked at a nearby hospital. Late at night, I became furious at the loud talking, laughing, and general merriment, and I got up from my bed, dressed, and went out into the yard with a blanket to sleep in my treehouse. After a few hours, the guests had all departed, and my father came out into the yard and called for me to come in. But I chose not to answer. The next morning I received one of the few whippings of my boyhood, all of which I remember so well.

One of the rare times I ever felt desperately sorry for my father was when he went to my uncle’s general store to be measured by a traveling salesman for a tailor-made suit of clothes, the first of his life. Ordinarily all our clothes were ready made, so we waited with a keen anticipation for Daddy’s new suit to arrive, and after it did, on the next Sunday morning when we began to dress for Sunday school and church, Daddy opened the box with a great flourish. All the family entered the bedroom, gathered around the fireplace while Daddy began to put on his suit.

Alas, some terrible mistake had been made! The custom-made clothes were twice as large as my father. I remember that no one in the family laughed.

My father was a natural leader in our community, and with the advent of the Rural Electrification Program, when I was about thirteen years old, my father became one of the first directors of our local REA organization. He then began to learn the importance of political involvement on a state and national basis to protect the program that meant so much in changing our farm lifestyle. He served for many years as a member of the county school board, and one year before his death in 1953, he was elected to the state legislature.

An almost unbelievable change took place in our lives when electricity came to the farm.

The continuing burden of pumping water, sawing wood, building fires in the cooking stove, filling lamps with kerosene, and closing the day’s activity with the coming of night . . . all these things changed dramatically. Farmers began to have county and regional meetings to discuss the changes that were taking place in their lives, to elect REA directors, to discuss national legislation, to determine rate structures, to bargain with the Georgia Power Company on electricity supplies, and to determine which new areas would be covered next by the electric power line.

In general, our family’s horizons were expanded greatly.

The new availability of electricity was a great relief to me in a curiously personal way.

Electric mule clippers took the place of the handcranked machine which Daddy had always used to shear the mules and to cut my hair. On one early occasion, I was planning to go to Columbus to visit my mother’s parents, and I was very nervous about the long trip. In preparation for the trip my father took me into the backyard to cut my hair. The clippers were driven by a flexible steel cable which another person turned by a hand crank. Daddy’s hand slipped, and a big gap was cut out of the hair on top of my head. After studying the situation for a few minutes, he decided that the only solution was to clip my head completely so at least it would be uniform, and this he did.

I was deeply embarrassed and wanted to stay at home until my hair grew out. Finally, Daddy found a cap that I could wear, and I went to Columbus to visit for about a week and then returned home. Later, my mother asked my grandmother what she thought of me, and Grandma reported that I was a fine boy but acted in a very peculiar way. She told Mother I was the only child she had ever seen who slept and ate while wearing a cap!

One reason I never thought about complaining about the work assigned to me as a boy was that my father always worked harder than did I or anyone else on the farm. In nearby Plains, Daddy opened a small office where he bought peanuts from other farmers on a contract basis for a nearby oil mill, and where he eventually began to sell fertilizer, seed, and other supplies to neighboring farmers.

I never even considered disobeying my father, and he seldom, if ever, ordered me to perform a task; he simply suggested that it needed to be done, and he expected me to do it. But he was a stern disciplinarian and punished me severely when I misbehaved. From the time I was four years old until I was fifteen years old he whipped me six times, and I’ve never forgotten any of those impressive experiences. The punishment was administered with a small, long, flexible peach-tree switch.

My most vivid memory of a whipping was when I was four or five years old. I had been to my Sunday school class, and as was his custom, Daddy had given me a penny for the offering. When we got back home, I took off my Sunday clothes and put the contents of my pocket on a dresser. There were two pennies lying there. Daddy thus discovered that when they passed the collection plate I had taken out an extra penny, instead of putting mine in for the offering. That was the last money I ever stole.

Most of my other punishments occurred because of arguments with my sister Gloria, who was younger than I but larger during our growing years. I remember once she threw a wrench and hit me, and I retaliated by shooting her in the rear end with a BB gun. For several hours, she re-burst into tears every time the sound of a car was heard. When Daddy finally drove into our yard, she was apparently sobbing uncontrollably, and after a brief explanation by her of what had occurred, Daddy whipped me without further comment.

I never remember seeing Daddy without a hat on when he was outdoors. He laughed a lot and almost everybody liked him. He kept very thorough and accurate farm and business records and was scrupulously fair with all those who dealt with him. He finished the tenth grade at Riverside Academy in Gainesville, Georgia, before the First World War. So far as I have been able to determine this was—at that time—the most advanced education of any Carter man since our family moved to Georgia more than two hundred years ago.

My father died in July of 1953, a victim of cancer. He was extremely intelligent, well read about current events, and was always probing for innovative business techniques or enterprises. He was quite conservative, and my mother was and is a liberal, but within our family we never thought about trying to define such labels.

My mother is a registered nurse, and during my formative years she worked constantly, primarily on private duty either at the nearby hospital or in patients’ homes. She typically worked on nursing duty twelve hours per day or twenty hours per day, for which she was paid a magnificent six dollars, and during her off-duty hours she had to perform the normal functions of a mother and a housekeeper. She served as a community doctor for our neighbors and for us and was extremely compassionate towards all those who were afflicted with any sort of illness. Although my father seldom read a book, my mother was an avid reader, and so was I.

Quite often my mother was not paid for her nursing service at all, at least not in cash. I remember that once for weeks Mother nursed a young girl who had diphtheria. The girl’s parents were very poor. Eventually she died, and a few weeks later the girl’s father drove into our yard with a one-horse wagon loaded down with turpentine chips. He had traveled more than a day to get there.

Although the wood chips had little monetary value, they were extremely helpful to us because they burst instantly into a roaring flame when touched with a match and were useful in starting a fire in the stove or fireplace, an early morning necessity for us. I remember that we unloaded the turpentine chips into a pit used for storing ferns and flowers during the winter, and we benefitted from their use for several years.

My mother’s youngest sister, “Sissy,” was very close to us, and when she was married, we had the wedding dinner at our home. The whole family worked for days preparing a delicious meal to impress our many visitors who came there from throughout the state of Georgia. The main course was chicken salad. In the midst of the meal, as our guests sat under the shade trees in our yard in their fancy clothes, dozens of chickens began to die before our eyes.

We scrambled wildly to pick up the dead chickens before our guests could see them. No one died of ptomaine poisoning, and we discovered later that those chickens in our yard had eaten poisonous nitrate of soda which had been left in open bags in the field adjoining our house.

My black playmates were the ones who joined me in field work that was suitable for younger boys. We were the ones who “toted” fresh water to the more adult workers in the field. We mopped the cotton, turned sweet potato and watermelon vines, pruned the deformed young watermelons, toted the stove wood, swept the yards, carried slop to the hogs, and gathered eggs—all thankless tasks. But we also rode mules and horses through the woods, jumped out of the barn loft into huge piles of oat straw, wrestled and fought, fished and swam. Their mothers had complete authority over me when I was in their homes (I don’t remember that their fathers did). My best and closest friend while growing up was named A. D. Davis. He now works for a sawmill and has, I believe, fourteen children.

During high-school years we had at Archery a baseball team consisting of ten players. (The tenth player was the “back stop” who stood behind the catcher to block balls which escaped.)

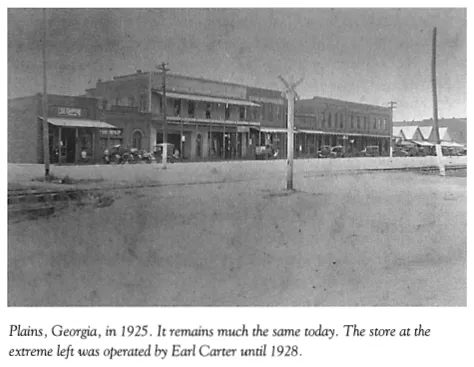

The nearby town of Plains had a population of about 550, and was for me a center of commerce, education, and religion. A small cotton gin was located there, and there was a market for peanuts, watermelons, eggs, cantaloupe, cream, butter, blackberries, and other farm products.

Our school was located in Plains, where I completed eleven years, in those days a total high school education, before going off to college; and each Sunday we attended the Plains Baptist Church, where my father was a Sunday school teacher.

During my childhood I never considered myself a part of the Plains society, but always thought of myself as a visitor when I entered that “metropolitan” community.

In my class in the Plains school we had about thirty students when we started, and eleven years later our graduating class consisted of twenty-four members. Total membership in the Plains Baptist Church was about 300, but we ordinarily had and still have about 150 at Sunday school for each service. It is by far the biggest church in town.

My father had a little store next to our home where we sold overalls, work shoes, sugar, salt, flour, meal, coffee, Octagon Soap, tobacco and snuff, rat traps, castor oil, lamp wicks, and kerosene. Our own farm products were kept in stock, such as syrup, side meat, lard, cured hams, loops of stuffed sausage, and wool blankets. The store was open on Saturdays during payday and otherwise was unlocked only when a customer came, almost always during meal times, for a nickel’s worth of snuff or kerosene.

During the field-work season all the workers arose each morning at 4 A.M., sun time, wakened by the ringing of a large farm bell. We would go to the barn and catch the mules by lantern light, put the plow stocks, seed, fertilizer, and other supplies on the wagons, and drive to the field where we would be working that day. Then we would unhook the mules from the wagon harness, hook up the plows, and wait for it to be light enough to cultivate without plowing up the crops.

When I was a small boy, I carried water from a nearby spring in buckets to the men, and filled up the seed planters and fertilizer distributors, or ran errands. Later, I was proud to plow by myself.

We worked steadily with brief breaks to let the mules rest, or for breakfast and dinner, and then at sundown we would hook the mules to the wagons and go back to the barn lot. There was no running water there, so we then fed and pumped water for the livestock and went home for supper and to an early bed.

On other days we moved slowly up and down the field, hoeing weeds and grass. There was always a lot of conversation, and at times the whole group sang together to provide a rhythmical beat for the chopping of the hoes.

Our blacksmith shop was a small building near the barn with, of course, a dirt floor. The forge and anvil, drill press, and emery wheel were used daily to repair farm tools and sometimes to make them. Our horses and mules were shod there, and our plow points were sharpened.

A few of us did this work routinely, but Daddy handled the more difficult jobs. The rudiments of blacksmithing were a required part of our Future Farmers of America training at school; and the shop was always filled with and surrounded by every imaginable kind of scrap-iron.

We learned to appreciate the stability of the agricultural programs brought about by federal government action, and we cooperated fully in the soil and water conservation service plans for erosion control and the enhancement of wildlife. But my father never forgave President Franklin Roosevelt for requiring that hogs be slaughtered and cotton be plowed up when these production control programs first went into effect. He never again voted for Roosevelt.

Wages paid on the farm were very low. I remember when they increased from $1.00 per day up to $1.25 for adult men. Women were paid $.75 and...