- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A history of Britain's healthcare system, from the Victorian era to the post-World War II beginnings of the NHS to the Coronavirus pandemic.

The Coronavirus pandemic in 2020 has changed life as we know it and thrust the NHS into the spotlight. A nation in lockdown has adorned windows with rainbows and stepped onto doorsteps every Thursday to celebrate the people who are risking their lives by turning up to work. But as the grim reports of deaths from the disease cumulate, along with stories of insufficient protective equipment for staff, there is hope that the crisis will raise awareness and bring change to the way the NHS and its people are treated.

At midnight on 5 July 1948, the National Health Service was born with the founding principal to be free at the point of use and based on clinical need rather than on a person's ability to pay. Over seventy years since its formation, these core principals still hold true, but the world has changed. Persistent underfunding has not kept pace with increased demand for healthcare, leading to longer waiting times, staffing shortages and low morale.

This book traces the history of our health service, from Victorian healthcare and the early 20th century, through a timeline of change to the current day, comparing the problems and illnesses of 1948 to those we face today. Politics and funding are demystified and the effects of the pandemic are discussed, alongside personal stories from frontline staff and patients who have experienced our changing NHS.

"Ellen's book takes us on an emotional journey through the history of our beloved NHS. This should be compulsory reading for anyone who thinks the NHS is safe in the hands of anyone but the Labour Party. Absolutely enthralling." —Books Monthly

The Coronavirus pandemic in 2020 has changed life as we know it and thrust the NHS into the spotlight. A nation in lockdown has adorned windows with rainbows and stepped onto doorsteps every Thursday to celebrate the people who are risking their lives by turning up to work. But as the grim reports of deaths from the disease cumulate, along with stories of insufficient protective equipment for staff, there is hope that the crisis will raise awareness and bring change to the way the NHS and its people are treated.

At midnight on 5 July 1948, the National Health Service was born with the founding principal to be free at the point of use and based on clinical need rather than on a person's ability to pay. Over seventy years since its formation, these core principals still hold true, but the world has changed. Persistent underfunding has not kept pace with increased demand for healthcare, leading to longer waiting times, staffing shortages and low morale.

This book traces the history of our health service, from Victorian healthcare and the early 20th century, through a timeline of change to the current day, comparing the problems and illnesses of 1948 to those we face today. Politics and funding are demystified and the effects of the pandemic are discussed, alongside personal stories from frontline staff and patients who have experienced our changing NHS.

"Ellen's book takes us on an emotional journey through the history of our beloved NHS. This should be compulsory reading for anyone who thinks the NHS is safe in the hands of anyone but the Labour Party. Absolutely enthralling." —Books Monthly

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Pre-NHS Britain

Organised health care really started to take shape in the nineteenth century, but clearly medicine and healthcare have been around a whole lot longer than this. Whole libraries are dedicated to the history of medicine, and this chapter aims to present a snapshot of healthcare and medicine over the last few centuries, to gain a flavour of what Britain was like, and to appreciate how life has evolved into the system we know today.

The Middle Ages (500-1500) and The Renaissance (1400-1700)

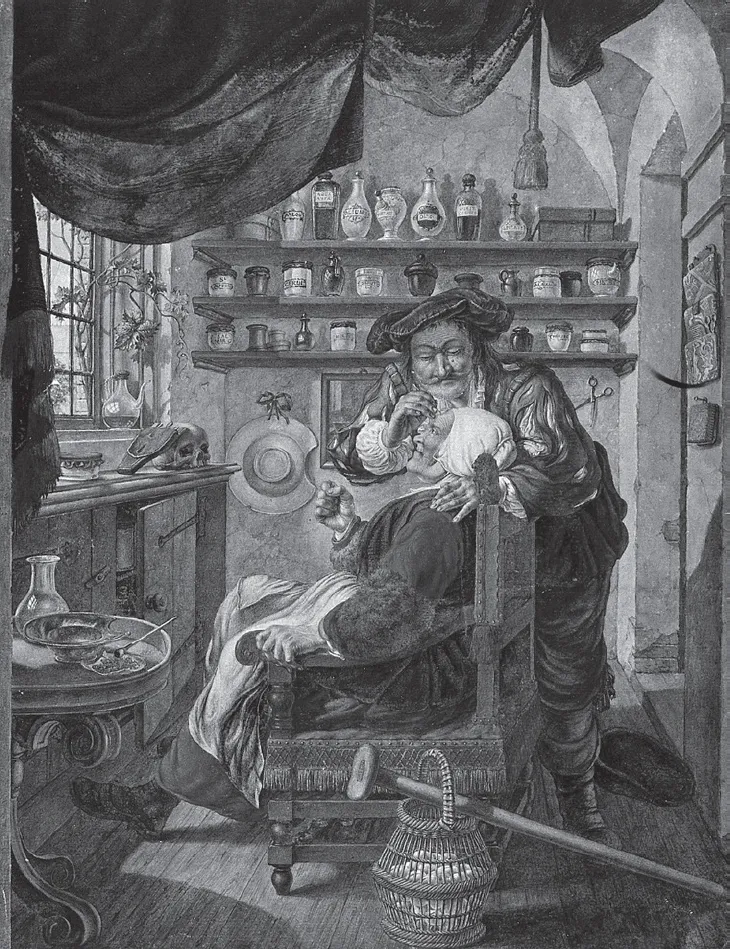

Medieval medics were pretty powerless in the face of disease, and medical knowledge and ideas about treatments were often based on superstition. The cause of disease was considered supernatural, and herbal remedies were commonplace.

Responsibility for the poor, sick and elderly traditionally fell to the church, and prior to the development of hospitals, townsfolk would turn to their nearest monastery for help with their sick. Prayer rituals were used to heal, and monks produced some of the earliest medical texts documenting the herbal mixtures they used to return their patients back to good health. Religious men were forbidden to spill blood (by Papal decree), so it was common at the time for barbers to assist monks in procedures considered dirty and beneath them – such as bloodletting and leeching, extracting teeth, lancing boils and doing a quick short back and sides (Box 1.1)

In the late 1530s, there were nearly 900 religious houses in England, whose primary function was to provide lodging for travellers and pilgrims, and to act as almshouses and schools. They typically imposed local taxes to assist them in providing such charity. Following the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536-1540) by Henry VIII, almost all of these institutions were disbanded, creating considerable hardship for the poor and destitute who were thrown out onto the street. Only three London hospitals survived the dissolution, after the citizens of the city petitioned for them to remain – St Barthlolomew’s (Bart’s), St Thomas’s and St Mary’s of Bethlehem. They were endowed by the king himself, as the first example of secular support being provided for medical institutions. They remained the principal hospitals in the country until the voluntary hospital movement began in the nineteenth century.

The Renaissance was a period of discovery in medicine. The scientific method was established, and universities established schools of medicine. Artists such as Da Vinci revolutionized painting, and dissection allowed the human body to be studied in more detail, which improved knowledge of anatomy. The invention of the printing press allowed ideas to be disseminated more quickly around Europe, allowing knowledge to be shared. In the 1620s, William Harvey showed that blood circulates, challenging Galen’s theory of humours (that disease was due to an imbalance of the four humours – blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile) which had been fundamental for centuries; and queried the need for the well-established practice of bloodletting.

Outbreaks of infection still defied medical knowledge. The Black Plague rampaged through Europe in the fourteenth century, recurring in outbreaks until the nineteenth century, claiming over 200 million lives. People believed the pandemic was a punishment from God, and blame was dispensed indiscriminately to groups deemed responsible – such as beggars, lepers, Jews and pilgrims. Individuals with skin diseases such as acne or psoriasis were exterminated, and religious fanaticism bloomed. ‘Cures’ for the plague included pressing a plucked chicken against the plague sores; smoking tobacco (a novel substance recently introduced from the New World); use of posies and perfumes; dried toad; leeches; a lucky hares foot We now know that plague can be successfully treated with antibiotics, but these, along with public health measures, had not yet been discovered.

Modern History

Improvements in public health and understanding of infection began to develop in the 1800s. In 1796, Edward Jenner discovered vaccinations, by famously using cowpox to protect against smallpox; and some 60 years later, Louis Pasteur developed germ theory, which proved a link between dirt and disease.

The Industrial Revolution resulted in more families moving to towns and cities, often sharing squalid, overcrowded accommodation, and standards of public health were poor. Pollution, contaminated water and a limited diet allowed infectious diseases to flourish and cholera epidemics were common place. An increased understanding of disease and hygiene led to improvements in public health standards. In 1854, John Snow showed the source of the London cholera epidemic to be the communal water pump used at Broad Street. Edwin Chadwick was a social reformer, who worked with the Poor Law Commission. He raised awareness that dirt and squalor are associated with high mortality rates, and that the misery faced by the poor was something the government could control, and not due to some innate shortcoming of the working class. His work led to the first Public Health Act in Britain in 1848, 100 years prior to the creation of the NHS. This led to improvements in the sewage system and building regulations, which contributed to declining mortality rates.

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, great advances were seen in medicine and public health. Anaesthesia and aseptic surgery were introduced; game changing discoveries were made – such as penicillin, x-rays and radium, and blood groups which enabled blood transfusion. The two World Wars shaped medicine. The injuries caused by the heavy artillery of the First World War meant that medicine was forced to pioneer new techniques in plastic surgery and skin grafting, and develop specialities such as maxillofacial surgery. The influenza pandemic of 1918 overshadowed the end of the war, and will be covered in chapter 5. Rationing improved the diets of some and encouraged healthy eating. Events during the Second World War created the stage for the formation of the NHS. Social barriers were broken down and brought people together, looking for improvements in society – more about this in chapter 2.

Workhouses and the Poor Law

The history of the workhouse as an institution to solve the enduring problem of poverty spans over three centuries and was an important precursor to the NHS. During the reign of Elizabeth I, in 1601, the Act for the Relief of the Poor (which is now known as the Old Poor Law) was passed to deal with beggars, who were viewed as a threat to civil order. This Act made local parishes responsible for the poor and decreed that the ‘impotent poor’ – the old and sick – were to be cared for in poorhouses, while able bodied paupers should be given work and sent to prison if they refused. Individual parishes were responsible for overseeing their own areas, and at its inception, local populations were small enough for communities to be aware of each other’s circumstances, meaning the ‘idle poor’ were unable to abuse the system. Relief under the ‘Old Poor Law’ was either in the form of ‘indoor relief’ – assistance inside a workhouse or almshouse – or ‘outdoor relief’, which involved payment in the form of money, food, blankets or clothing. Funding to provide this assistance was collected by Overseers of the Poor, who levied local property owners (a tax that we still pay today now, known as council tax).

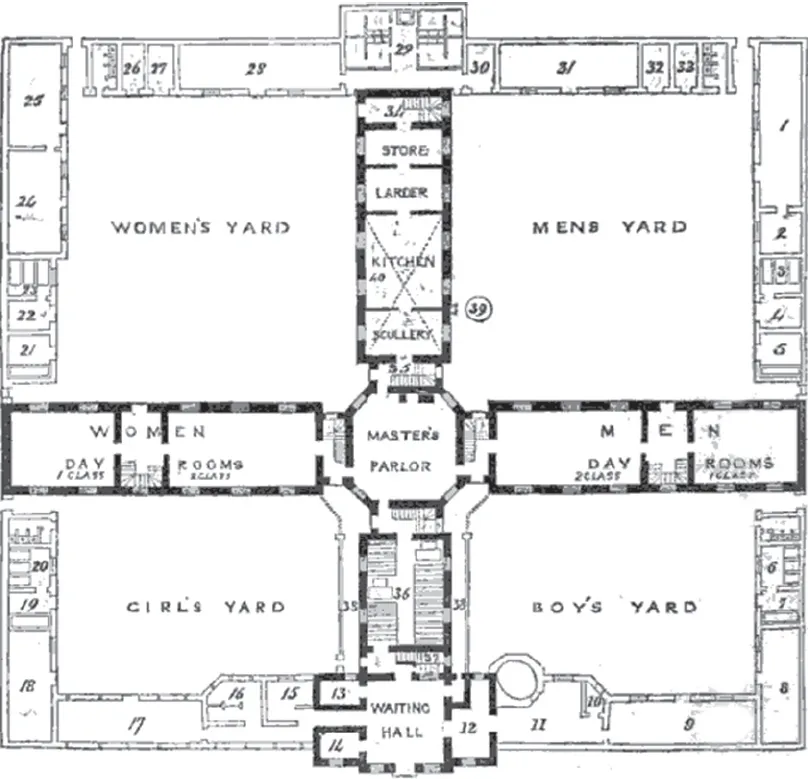

Sampson Kempthorne Workhouse designed for 300 paupers. Sampson Kempthorne (1809–1873) (via Wikimedia Commons)

1. Work Room

2. Store

3. Receiving Wards, 3 beds

4. Bath

5. Washing Room

6. Receiving Ward, 3 beds

7. Washing Room

8. Work Room

9. Flour and Mill Room

10. Coals

11. Bakehouse

12. Bread Room

13. Searching Room

14. Porter’s Room

15. Store

16. Potatoes

17. Coals

18. Work Room

19. Washing Room

20. Receiving Ward, 3 beds

21. Washing Room

22. Bath

23. Receiving Ward, 3 beds

24. Laundry

25. Wash-house

26. Dead House

27. Refractory Ward

28. Work Room

29. Piggery

30. Slaughter House

31. Work Room

32. Refractory Ward

33. Dead House

34. Women’s Stairs to Dining Hall

35. Men’s Stairs to ditto

36. Boys’ and Girls’ School and Dining Room

37. Delivery

38. Passage

39. Well

40. Cellar under ground

There was no uniformity to the system throughout the country, and many paupers migrated towards the more generous parishes. During the seventeenth century, the workhouses evolved as a way of allowing parishes to avoid outdoor relief payments. By 1776, in London alone, over 16,000 people were housed in one of the city’s eighty workhouses – which amounted to 1-2 per cent per cent of the capital’s population. There was rumbling dissatisfaction with this system, and its critics considered the conditions in many of these ‘Paupers Palaces’ to be too comfortable, encouraging idleness and pauperism. The New Poor Law was therefore passed in 1834, to cut expenditure and abolish pauperism by attempting to ensure only the truly destitute would accept poor relief. Those eligible could not be better off than the worst paid independent worker, and if they were truly needy, they would be offered the workhouse – a harsh and austere regimen which only the desperate would enter willingly. It was not a prison, and people could come and go if they found work, but the regime was strict and to go into the workhous...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgement

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Chapter 1 Pre-NHS Britain

- Chapter 2 The Formation of the NHS

- Chapter 3 Timeline of the NHS;

- Chapter 4 The Modern NHS

- Chapter 5 Pandemic

- Sources and Additional Reading

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The NHS by Ellen Welch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia britannica moderna. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.