![]()

Part I

Gender and Careers in the Legal Academy

![]()

1

Gender and Careers in the Legal Academy in Germany: Women’s Difficult Path from Pioneers to a (Still Contested) Minority

ULRIKE SCHULTZ

Abstract

In Germany positions in the academy are still prestigious, in the legal academy even highly prestigious. In 2019, less than 15 per cent of the full chairs in law faculties were occupied by women, although since the early 2000s the number of women studying law has equalled that of men and by 2019 stood at 56 per cent. In other fields there is also a gap between the proportions of students and university teachers, but it is worst in law and medicine, the old and most prestigious professions (Schultz et al 2018: 151 ff).

A long qualifying path of 15 to 20 years with continuing job insecurity to a chair in law is unattractive, especially for women who want to have children. It falls into the ‘rush-hour of life’, a phase in which careers are built and families are founded. Many women leave the academy after completing their doctoral studies, finding more attractive alternatives in the judiciary, the civil service, in business and the legal profession, with better pay and, as far as the civil service is concerned, shorter and more regular working hours, uncontested maternity and parental leave and no pressure to publish. Academic careers are hindered by systemic and individual factors, of which cultural specificities in law and law faculties play an important role.

1.THE JURPRO PROJECT1

Why are there so few women law professors in Germany? Compared with other Western countries Germany has a marked deficit of women in leading positions2 and a considerable gender pay gap.3 To find out what hinders them, I applied for a governmental grant in a funding line called ‘Women to the Top’4 and, between 2011 and 2014, with a group of scholars from various disciplines (law, sociology, pedagogy and a practitioner qualified in human resources and experience in equal opportunities work at our university), I researched the career paths and conditions in the legal academy.5

Our project aims were

•To get a detailed insight into the situation of female law professors.

•To capture the causes for women’s underrepresentation in senior academic positions in law faculties.

•To define career obstacles as well as career aids.

•To describe the factors constituting the faculty culture.

•To analyse existing equal opportunity structures and institutions and their impact.

•To identify factors which could enhance the organisational structure and culture in law faculties.

•To propose measures of efficient career support for women.

We used a mixed methods approach. For a theoretical foundation, we analysed the literature on women in the academy, in research and science. To describe the field, we evaluated the literature on legal education and any other literature from which we could extract information about the culture of the legal academy,6 as well as about equal opportunities and personnel management. We did a textual analysis of obituaries of professors of public law to filter out the cultivated image of the ideal law professor, and we analysed the construction of femininity in teaching materials. We collected and evaluated all relevant quantitative data available. For a differentiated understanding of the structures, subjective views and cultural influences in the field and its actors, we did 91 interviews between 2011 and 2016 throughout the Federal Republic of Germany, 44 with female faculty at all stages (including some retired women ‘pioneers’), 20 with male faculty, five with women who had dropped out of the academy, 20 with equal opportunity officers, and two with university vice-chancellors. I analysed the CVs of the 135 women law professors we could find on the internet in 2013. In parallel, I set up a website on law and gender for which I interviewed 25 colleagues on gender issues in law and drew up eight personality portraits.7

To analyse the interviews, we used grounded theory as a qualitative explorative method (Strauss and Corbin 1990; Strübing 2004). Parts of the interviews were also used to describe the field and its processes (Schultz et al 2018: 47 ff).

2.EXCLUSION AND OBSTACLES: THE HISTORY OF WOMEN IN THE LEGAL ACADEMY

While in Europe generally female students were first allowed to attend university lectures in the latter part of the nineteenth century, German women had to wait even longer – in the case of law until the beginning of the twentieth century. Women were regarded as too emotional and subjective as well as too fragile for the hard and responsible work awaiting them as jurists (Schultz 1990, 2003b) They had a long way to go.

The first women were formally admitted to German law faculties between 1900 and 1909. From 1912 they could sit the ‘first state examination’,8 while yet another decade needed to pass prior to the first woman, Maria Otto, being permitted to take the second qualifying state exam (in Bavaria) (Röwekamp 2005). By 1914 there were 51 women law students (0.61 per cent of a total of 9,003 and 1.4 per cent of all women studying at university), rising to 74 in 1917 and 450 in 1919 (2.6 per cent of a total of 17,224). The democratic Weimar Republic, founded after Germany lost the First World War, had given women the right to vote and be elected to political office (from 1918). But a special law was still needed in 1922 to admit women to the ‘administration of justice’, ie, to the judiciary, prosecution service and advocacy. The number of those taking advantage of this newly gained entitlement remained however miniscule (Schultz 2003b; Schultz et al 2018: 69 ff). The patriarchal family law that had come into force in 1900,9 economic stringency caused by the high reparations Germany had to pay after the war, combined with the imminent world economic crisis, created a hostile environment for women’s career ambitions. Due to a strong male culture, the academy remained even less accessible for women than either the judiciary or the advocacy.

The first (and until the end of the Second World War the only) woman to complete her habilitation, which in Germany is a necessary requirement for an academic career, was Magdalene Schoch, who specialised in international, English and American law, as well as comparative law in Hamburg in 1932 under Albrecht Mendelssohn Bartholdy. She never got a chair. As Jews were expelled from public office following the seizure of power of the National Socialists in 1933, Mendelssohn left Germany.10 Schoch, who, though not herself Jewish, was strongly opposed to the regime, emigrated to the United States in 1936 and never came back.

In 1933, Germany had 36 female judges (0.3 per cent of all judges) and 252 women lawyers (1.3 per cent of a total of 18,766), no female law professors and only a handful of women in other, lower positions in the legal academy. After 1933, women lost their public posts and were barred from entering state-controlled practical legal training and the judiciary. A civil court President declared in 1933 in line with the Nazi masculinity cult that ‘the inclusion of women in the judiciary is a serious injustice towards men and also women themselves. It is an intrusion into the holy principle of maleness of the state’. In 1934, a quota of 10 per cent for female students of law was introduced. In 1935 women were no longer admitted as judges or prosecutors and in 1936 Hitler decreed that they should ‘work as neither lawyers nor judges. In the judiciary they can only be kept for administrative tasks’ (Schultz et al 2018: 88). In 1938, what was left in academia were 12 female professors and 12 other tutors (‘Dozenten’) across the board, but none in law (references in Schultz et al 2018: 86 ff).

3.DATA11

3.1.Women Law Students and Lawyers

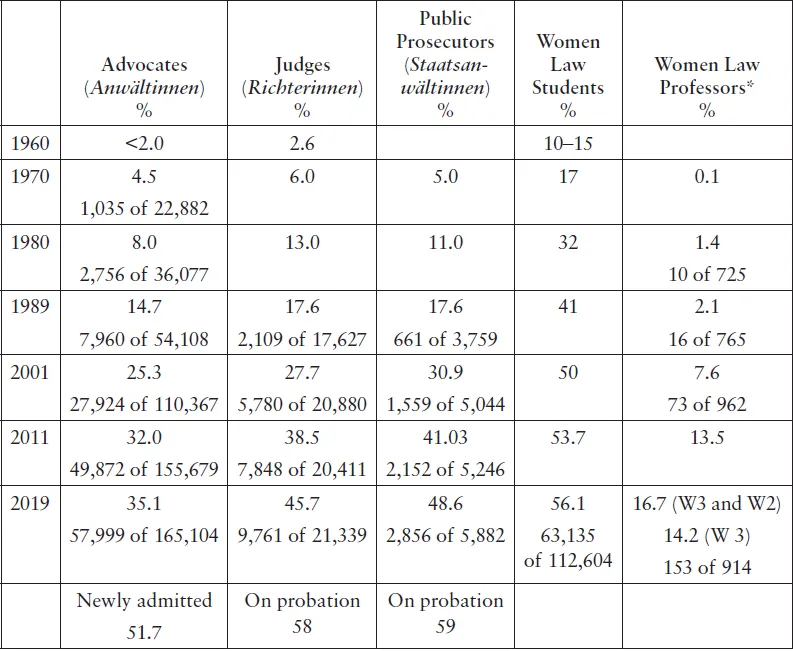

The numbers of female law students rose very slowly in the first three decades after the Second World War, gaining momentum only in the 1980s. Initially the proportion of female law students was much lower than that in other fields of study, as law continued to have the image of a hard male subject, but in the 1990s it drew level and since then the number of women law students has regularly exceeded the number of men. In the 1960s about 10–15 per cent of law students were women, in comparison to 27 per cent of all students including those in the natural sciences and technical subjects. In 1975 women made up 25.2 per cent (13,000 of 51,566) of all law students and in 2018 56.1 per cent of law students (63,135 of 112,604), compared with 48.6 per cent of all students. Law is now a preferred subject for women. Over the last 30 years women ranked law second to fourth among preferred subjects, whereas men ranked it fourth to sixth. The proportion of women law students increased from 5.2 to 6.9 per cent of all women students between 1975 and 2015, but that of men decreased from 8.7 to 5.9 per cent (Schultz et al 2018: 152 ff).

Table 1 Proportion of women in the legal professions

The increase in numbers after 1989 is due to reunification. The data before are only for West Germany.

* Women on chairs in law faculties. Not including women law professors in universities of applied sciences.

In the past three decades the number of women judges and prosecutors has risen in proportion to the number of law students. In 2017 their share in the official statistics was 45 per cent of judges and 46 per cent of prosecutors and the percentage of those being recruited is even higher than that of women law students.12

The increase in women in private practice started later. In 2017 their share was 34.4 per cent. A recent accelerated increase is due to the fact that since 2016 employed lawyers in the private and public economy can be fully admitted as advocates, and women prefer employed positions. In recent years the increase in advocates has slowed down. The share of women who are Anwaltsnotare, combining advocacy with notary functions, is still low at about 16 per cent, while solo-notaries make up about 24 per cent (Kilian and Schultz 2020).

3.2.Women in the Legal Academy

In the academy, development has been much slower than in the professions, and still does not show significant results. When I started to study law in 1966, there was one female law professor in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) – in criminology, which was considered a soft subject not to be taken seriously (Schultz et al 2018: 97–99). She had got the call to her chair just the year before. In the communist part of Germany, the German Democratic Republic (GDR), two women had done their habilitation and got chairs between 1946 and 1950, but even there the number of female law professors remained limited, although the qualification procedure (with a focus on Marxist-Leninist theory) was much less demanding than in the West (Schultz et al 2018: 94–97).13

The number of female law professors in the West has risen very slowly. It has mostly occurred in the past 10 years when equal opportunities policies and women’s advancement plans in universities have become at least symbolically more effective, and awareness generally has risen of the need to advance women’s careers. Still remarkably low, however, is their share of the big, fully equipped chairs (W3/C4)14 – only 14.2 per cent. For chairs with fewer staff and lower pay (W2/C3) there are more women. This is an indicator of a concealed gender pay gap.15 As law faculties have a strong position in the structure of universities due to their long history and the importance of their subject for politics and the state, law professors are better able to negotiate their salaries and get more extras than those in most other faculties.16

In 2015 there was one female law professor per 680 students, of whom 375 were women, but one male law professor per 133 students, of whom 73 were female. Today there are 43 law faculties in Germany, some with just one or two female law professors, two (Greifswald and Tübingen) without any at all. Thus, there is a good chance for a German law student never to encounter a woman in the position of professor of law.

In 2014, the average age for a call to a chair in law was 38.5 (35 for women, 40.4 for men). This was high by comparison with other faculties (Schultz et al 2018: 167). That women are younger is an effect of recent years, when more women have been taken in, while men of these generations still had to do military service.

3.3.The Leaky Pipeline

Most law professors start their careers as assistants. Whereas in 1980 only 15 per cent of these assistants were women, their number rose to 40 per cent in the year 2000 and settled thereafter at 47 per cent. There are three times as many research assistants as law professors, but nine times as many female research assistants as female law professors, a revealing career gap.

The first step for a career in the academy is a PhD dissertation. In 2017, 739 men and 464 women (38.6 per cent of the total) qualified, that is 5 per cent of women law students and 10.2 per cent of their male counterparts. This is higher than in other subjects, since traditionally the Dr. title in law represents not merely a qualification for an academic legal career, but also a distinction which enhances the value of applicants in the legal labour market generally.

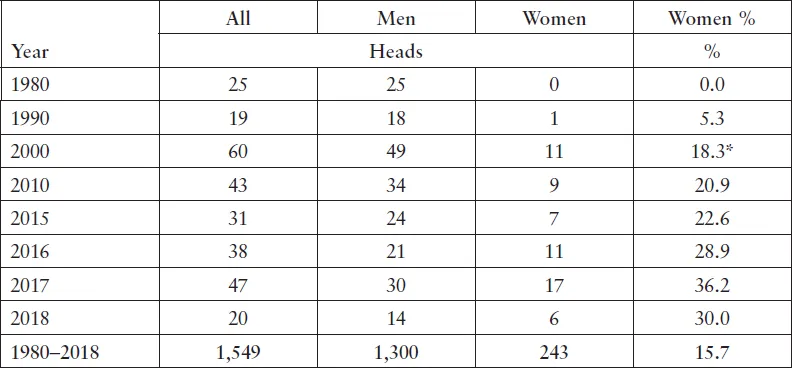

The next step is the habilitation thesis. This is a prerequisite for a call to a chair in traditional universities. From none in 1980, the number of habilitations by women has gradually increased to nine in 2010 (compared with 24 by men) and 17 in 2017 (compared with 30 by men) and slightly dropped to 6 of 20 in 2018.17

Table 2 Habilitation in law 1980 until 2015

From 1980 to 2018, 1,300 men and 243 women (= 15.7 per cent) have earned their habilitation. About 12 per cent of women who have completed their habilitation since 1990 have still not got a call to a chair, while for men the figure is below 10 per cent (Schultz et al 2018: 165 f). This shows that, at least until the end of the first decade of this century, even the few women with a habilitation had less chance of being appointed. The process whereby a high number of female law students is progressively reduced, with fewer becoming assistants, fewer still doing a doctorate and even fewer taking the habilitation, is described as a ‘leaky pipeline’. In Germany, law is the worst in this context, with only medicine coming close. Even in the still hard male subjects like engineering, the few women students have proportionally better chances of moving up to a chair than in law. It is clear that women in law are systematically disadvantaged, even if, due to the pressure from equal opportunities programmes, slightly more of them have got a call in recent years than their overall share in habilitations might suggest.18

3.4.Junior Professors in Law

In 2002, the institution of junior professor was introduced in Germany with the intention of offering a way to a tenured ...