![]()

PERIOD II

4800–4000 BC

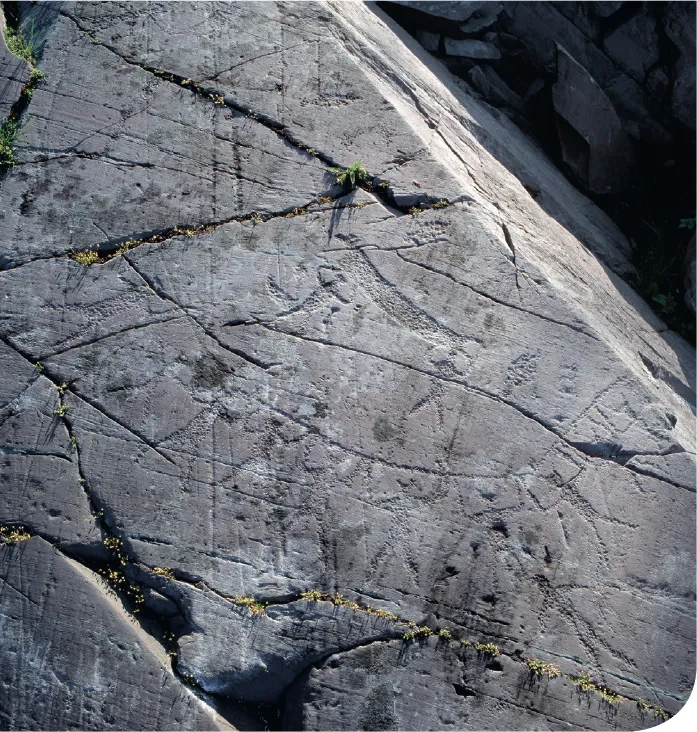

Figure 41

The figures are compact down across the rock surface. The photo was taken facing east-southeast.

Photo: Adnan Icagic

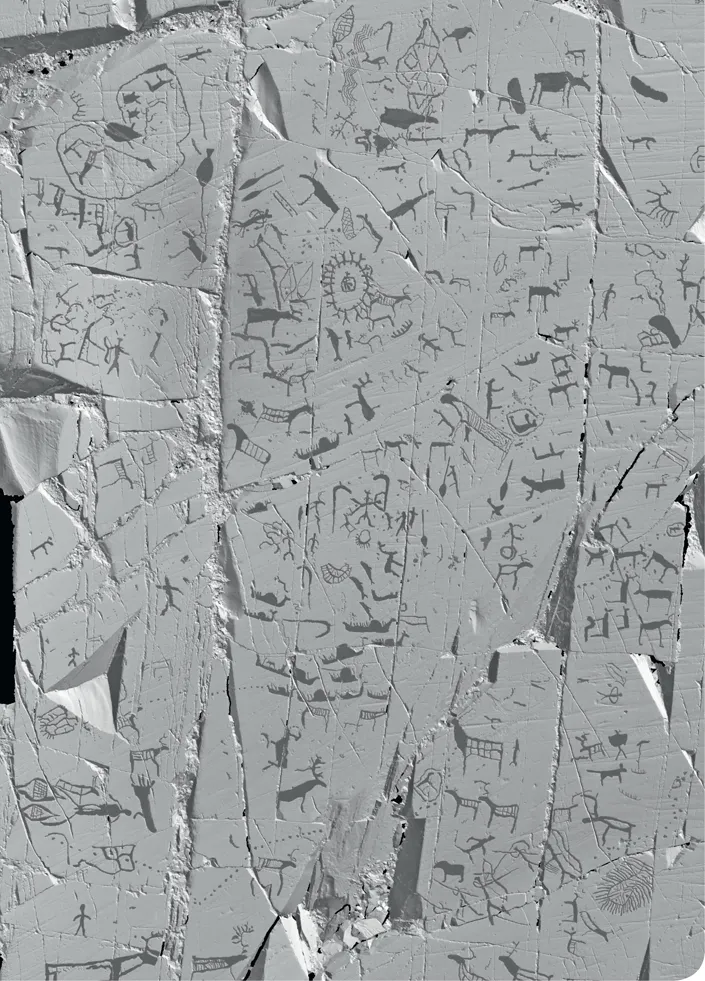

Figure 42

There are an impressive number of figures in the panel, compactly grouped and seldom carved on top of one another. It is as if they are at one and the same time a large, complicated tableau as well as multiple small compositions and stories. The figures have been digitally enhanced to give them a darker contrast on the rock surface. The photo is the result of high resolution optical threedimensional scanning, which does not record the colours of the rock surface. The topography of the rock and all the glacial striations from the Ice Age are very distinct.

Scanning: Metimur AB

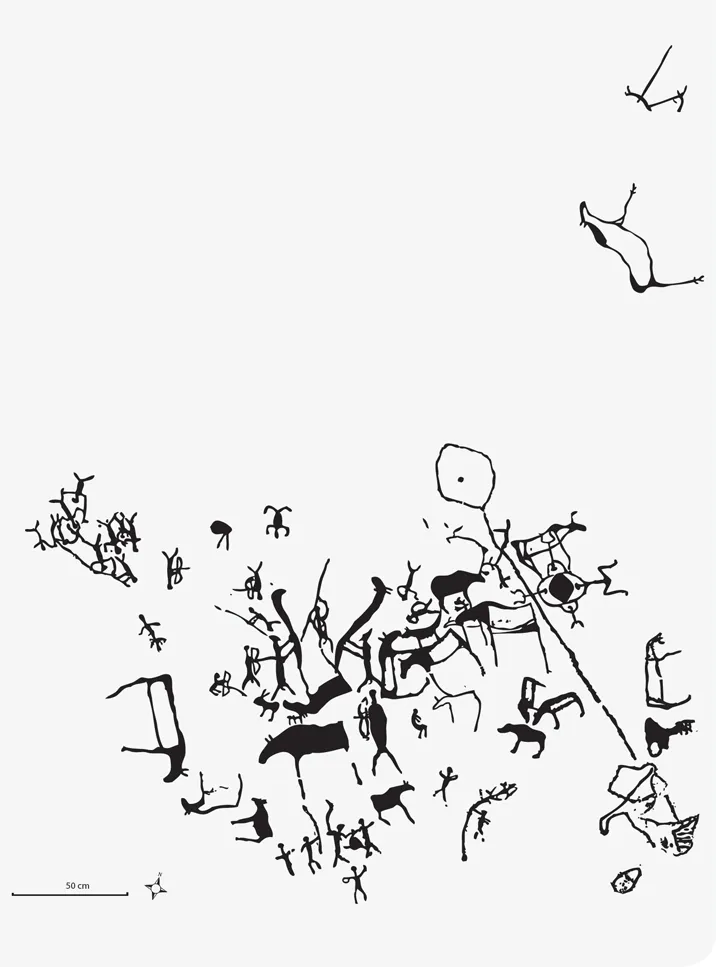

Figure 43

Perspective drawing of a section of the Bergbukten I panel showing the relationship between the rock’s topography and the figures. Topography and colours were also integrated parts of some of the stories that were illustrated and told. Seen from the east.

Drawing: Ernst Høgtun

The population in the Alta area during this era still had hunting, trapping and fishing as the basis for their livelihood. It is difficult to estimate the size of the population, but it was very likely small, amounting altogether to only a few hundred people. Based on excavations on Sørøya and surveys and finds in the areas around the Altafjord and other places in Finnmark, we assume that people lived in turf hut-like dwellings that were few in number and located on the same promontory or in the same bay. We know little, however, about the building materials used. Dwelling features of huts like these have been found at the head of Altafjord including Hjemmeluft/Jiepmaluokta, and across to Storekornes on the eastern side of the fjord, as well as at Isnestoften on the western side. It is assumed that tents were used during the summer by people who migrated to the hunting and trapping places, such as, for example, the terraces above Savtĉo in the Alta River (Simonsen 1992, 2001). Based on the few excavations done in the Altafjord area, in the coastal and inland areas (Simonsen 1961; Simonsen & Odner 1963; Renouf 1981; Engelstad 1986; Hesjedal et al. 1996) and the inland (Simonsen 1979a,b; Simonsen & Odner 1963; Halinen 2005), as well as on our knowledge of seasonal changes in nature, we have a general understanding of the way seasonal exploitation of resources in the area may have been carried out. They hunted reindeer, European elk (Alces alces), seals, small whales and birds, and they must have fished extensively in both saltwater and fresh water. They picked berries and gathered roots. They undoubtedly had deep knowledge about animals and plants, weather conditions and life in general in the world they inhabited.

At the same time, the relations between people, between individuals as well as between families, groups and clans, were decisive for the choices they took, whom they could marry, where they could live and with whom they could live, how they should behave, with whom they could hunt or pick berries, gather roots, etc. In many respects, this is not unlike relationships in many modern societies today. The knowledge they possessed was without a doubt vast and full of traditions. There were various types of specialists, a code of rules governing how tasks were to be accomplished and which other-than-human beings one should ally oneself with in every aspect of life. Some of the knowledge as well as the choices they made are expressed through the rock art.

The largest number of rock carvings and variations in motifs belong to this period. They are located at between 26.5 and 23 metres above today’s mean water level (Figure 44).

Most of the figures are relatively naturalistic, that is, they are easy to recognize from the original physical model, the very prototype. Among the animal figures, reindeer and elk predominate, followed by bears. In addition, there are a large number of humanlike figures and boat figures, as well as patterns or geometric figures for which no physical examples of a prototype have been found. Although it is easy to recognize boats, we do not know how representative they are, because no such boats have been preserved. The boats in the rock art represent the only direct knowledge in existence about boats in the north older than 2000 years.

Figure 44

The Hjemmeluft area. The transparent light blue layer shows a mean water level 23 m higher than today’s. Marked here as red circles, the panels with figures from Period II lie just above this. The younger panels can be seen beneath the simulated waterline. As land emerged, the figures were pecked into the rock surfaces in the younger tidewater zones and the older rock panels were no longer used.

Aerial photo: © Geovekst

![]()

HUMAN FIGURES

Figure 45

The human-like figures are depicted performing various activities. For example, to the right are four people holding an oval figure; at the bottom, people are returning from bird hunting, and just behind them, there is a person beating a drum. In the middle of the picture, two figures are holding poles topped with elk’s heads; another is brandishing a bow and arrow, and up to the left, there is some sort of procession. The panel is small, but full of content and focusing on humanlike figures performing activities.

Most of the human-like figures from this time period are depicted as line drawings with the body delineated by a thin or broad line. They are in boats; they fish, hunt, perform ceremonies and rituals. Human figures are central in all compositions in which they occur. Those in boats are discussed in the section on boats because it would be meaningless to separate one from the other. In a way, there is a distinction to be made between people performing activities in boats/on water and the rest of the human figures.

The figures brandishing bows and arrows at reindeer or spearing a bear in the chest describe humans in the act of hunting, whilst in some scenes, the figures have features indicating that they represent other-than-human beings, or humans masked as other-than-human beings. The problem is to distinguish between the three alternatives, if in fact there is a distinction to be made. Other than human life was shaped on models of mortal humans’ experience and knowledge, despite the fact that the other-than-human beings took the form of European elk, reindeer, fish or humans. Based on descriptions of early and existing hunting and trapping societies, one expects the other-than-human beings to have human features, sometimes combined with features of other animals, and sometimes incarnated wholly as animals. In other words, there are many alternative interpretations.

In certain instances, the very composition or context in which the figures occur gives us an inkling of what the individual figures represent. But even if we are able to group certain figures and exclude others, there is still a long way to go in understanding what the figures and compositions really meant. In one case, it appears as if a woman is riding on a reindeer’s back (Figure 58). Did people actually ride reindeer, or is this an illustration of a mythical event? In another instance, there is a scene with 11 human figures (Figures 45) in which one of them is holding a pole topped with an elk’s head (?); two are holding a child between them, and all of them appear to be in motion along a carved line. Whereas one is left with the impression that these are people performing some kind of ritual, one might also ask whether they represent different types of powers.

Figure 46

Night photography using artificial light requires a lot of expertise and patience. The rock surfaces are never uniform and even, so that light sources and the photographer must constantly change angles in order to capture the targeted motifs. Photographer Adnan Icagic at work.

Figure 47

A ritual associated with giving birth?

To the far right in the panel, four human figures are standing in a circle (Figures 45, 47). They are holding an oval figure between them. The human figure placed lowest is the smallest of the four, and the size of the others increases proportionally. The largest figure appears to be a woman squatting as if in a birthing position. This woman is grasping the opposite figure by the hands, whilst the other two opposite human figures are holding the wrists of their two counterparts. Perhaps all of these human figures are women, where the largest of them is giving birth and the three others are providing assistance during the birth. They are all holding an oval object during the birth, as if this is part of a ritual. What we see may also be a part of a narrative, a myth pertaining to a special birth and special humans or other-than-human beings. There is a reindeer bull and a cow turned toward the birthing scene, as if they are watching the birth. The reindeer cow partially overlaps the birthing scene; the problem, of course, as in so many other instances, is to determine which figures belong in this composition. There is also a reindeer bull with its back turned to the scene.

Figure 48

Two human-like figures lifting a boat, delineated to the right by a cleft and, to the left, by a fissure in the rock. Below are human-like figures holding a rope.

Figure 49

The southern portion of one of the larger panels from Period II with an abundance of figures. In the upper left is a scene in which people are in the process of scuttling a boat (Figure 84). To the right of this, a “death ritual” (?), elk, reindeer, geometric figures, and below, human figures holding elk’s head poles, a rare little whale, etc. To the far right: a depiction of sexual intercourse or a squid?

Photo: Adnan Icagic

Figure 50

Traditional sex position; to the left, two spears; to the right, a reindeer.

Figure 51

Sexual intercourse.

On the lower right of the panel, there is a small scene in which two human figures are carrying a large bird between them. The figure on the left is holding a long pole in its left hand, topped with what appears to be a bird’s head. On the left there are two additional human figures. One of them is holding a long pole in its right hand. It appears as if the figures are moving inwards in the panel. Behind them, there is another human figure carrying a circular object in its left hand and a short, straight object in its right hand, perhaps a drum and a drumstick, in a ritual associated with the hunting of the large bird being carried between the first two (Figure 45, 251)

The compact concentration of figures seems to be independent o...