![]()

1

The second ghetto and the dynamics of neighborhood change

I have walked the South Side Streets (Thirty-first to Sixty-ninth) from State to Cottage Grove in the last 35 days searching for a flat.

Anonymous to the Chicago Defender, November 28, 1942

Something is happening to lives and spirits that will never show up in the great housing shortage of the late ‘40s. Something is happening to the children which might not show up in our social records until 1970.

Chicago Sun-Times, undated clipping, Chicago Urban League Papers, Manuscript Collection, The Library, University of Illinois at Chicago

The race riot that devastated Chicago following the drowning of Eugene Williams on Sunday, July 27, 1919, was notable for its numerous brutal confrontations between white and black civilians. White hoodlums sped through the narrow sliver of land that was the Black Belt, firing their weapons as they rode, wreaking havoc and killing at least one person.1 Nor was that all. Aside from the many assaults and casualties taken in the Stock Yards district immediately west of the Black Belt, serious clashes occurred in the Loop and around the Angelus building, a rooming house that remained the abode of white workers in the predominantly black area around Wabash Avenue and 35th Street. Blacks retaliated by attacking whites unfortunate enough to be caught on their “turf.”2 By the time the riot ended, 38 persons – 23 blacks and 15 whites – lay dead and 537 were injured.3

In early April 1968, following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Chicago was again the scene of serious violence. Although labeled a “race riot,” the events of 1968 differed sharply from those of 1919. Instead of an interracial war carried on by black and white citizens, the “King riot,” largely an expression of outrage by the city’s black community, was characterized by the destruction of property. The deaths that did occur during the riots (there were nine) resulted primarily from confrontations between black civilians and the police or National Guard.4

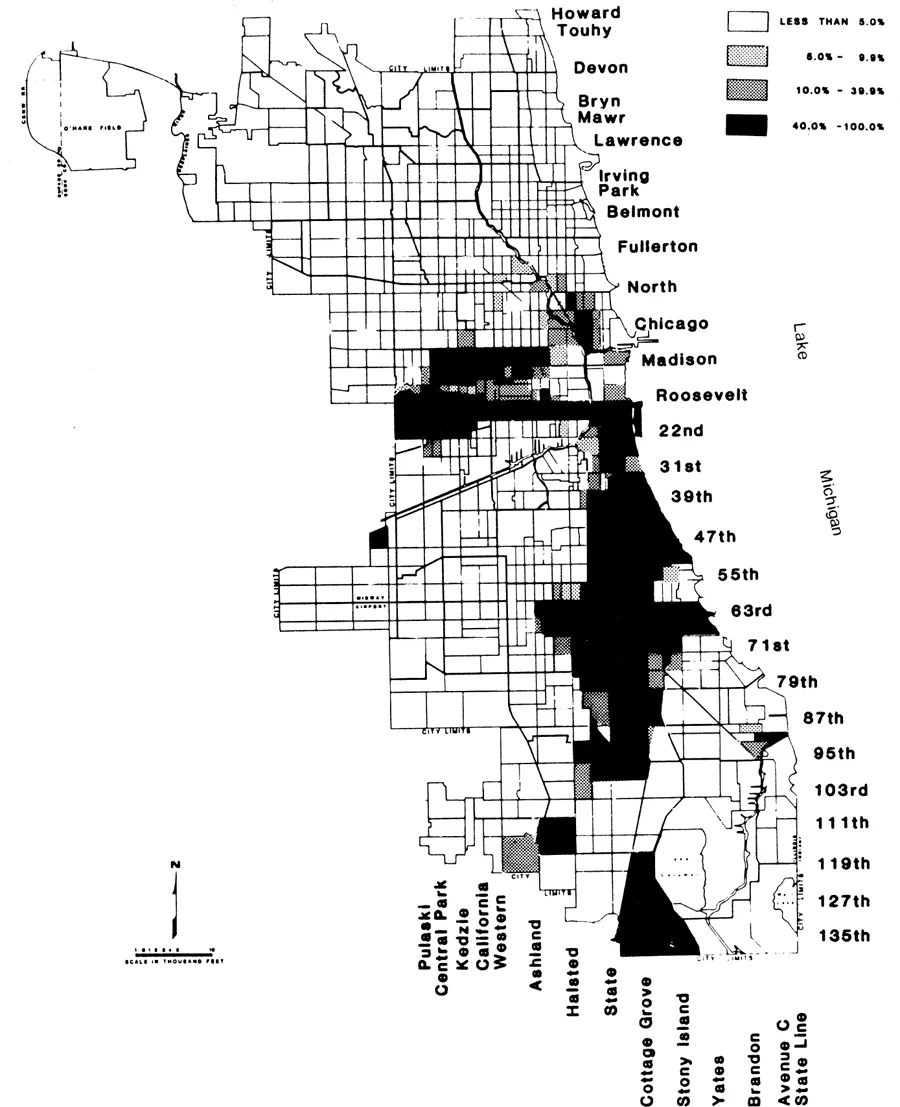

There were other significant differences as well. The worst rioting in 1968 occurred on the West Side. Merely a minor black enclave in 1919, by the time of Dr. King’s assassination Chicago’s West Side housed more than twice the number of blacks resident in the entire city during the earlier riot. A vast ghetto of relatively recent origin, the West Side thus established itself as a scene of racial tension to rival the older, and larger, South Side Black Belt. Moreover, the Loop, where blacks were viciously hunted in 1919, was now subjected to roving groups of black youths who had walked out of nearby innercity high schools. This time, however, harassment of pedestrians and petty vandalism replaced the deadly violence of the earlier era. Confrontations such as the one around the Angelus building were impossible in the more rigidly segregated city of the 1960s, and white injuries, reportedly few in number, generally occurred as motorists were unluckily trapped in riot areas. There were no armed forays into “enemy” territory. In sum, clashes between black and white Chicagoans (other than the police) were infrequent, fortuitous, and not lethal. The prevailing image of the 1968 disorder was evoked not by mass murder but by the flames that enveloped stores along a 2-mile stretch of Madison Street and those that engulfed similar structures along Western, Kedzie, and Pulaski avenues.5

The close relationship between the growth of the modern black metropolis and the changing pattern of racial disorder is clear. After an era of tremendous ghetto expansion and increasing racial isolation, “communal” riots on the scale of those that shook the nation in 1919 became impossible. The thought of white mobs attacking the black ghettos of the 1960s boggles the imagination. Additionally, the large concentration of blacks in the inner city rendered exceedingly unlikely the stalking and killing of individual blacks on downtown streets. The burning and looting of primarily white-owned property in massive black ghettos was the most visible manifestation of racial tension permitted in the modern city. Able to quarantine black neighborhoods, police were much less able to control actions taken within them. The eruption of the “commodity” riots of the 1960s heralded the existence, in Chicago at least, of that city’s “second ghetto.”6

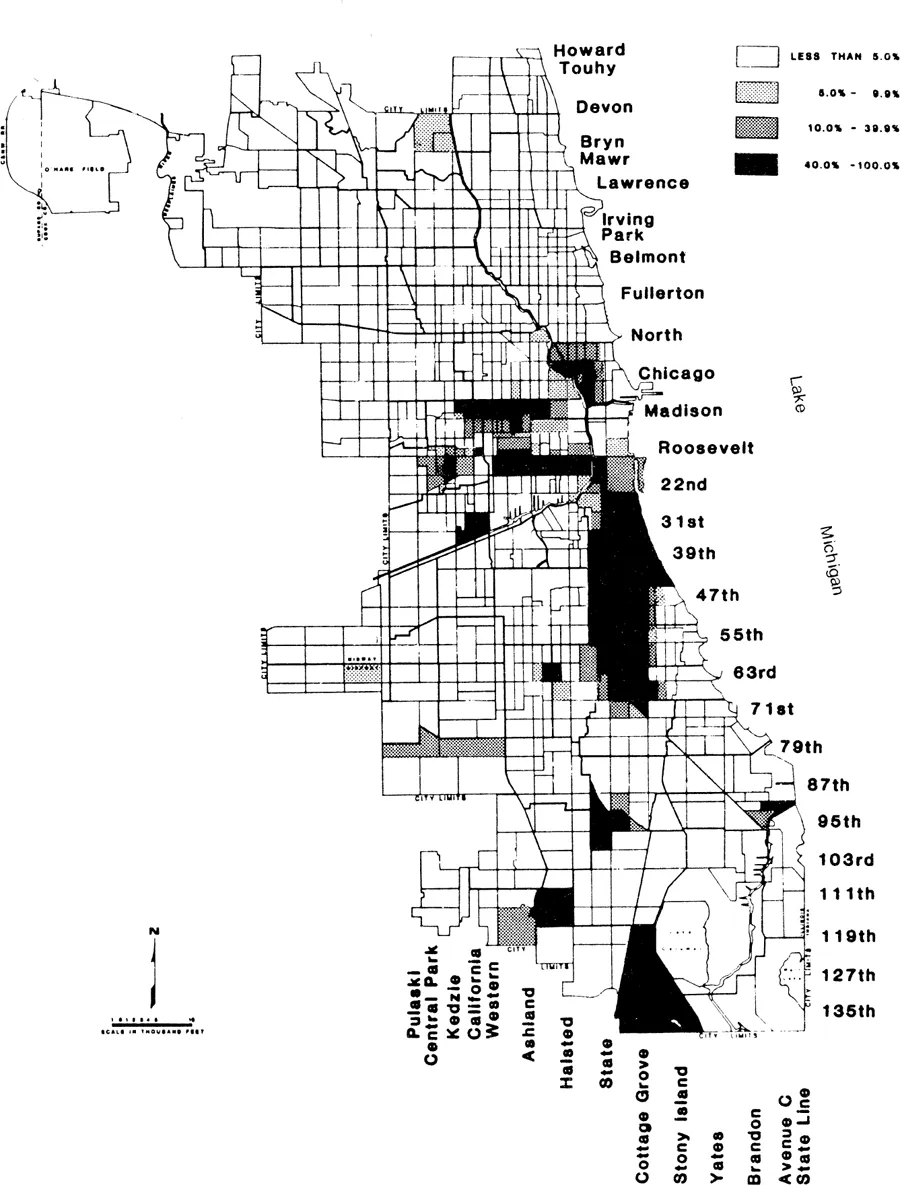

The reasons for making a distinction between the “first ghetto” of the World War I era and the “second ghetto” of the post-World War II period are quantitative, temporal, and qualitative. As Morris Janowitz noted in his analysis of racial disorders in the twentieth century, the “commodity” riots of the 1960s took place in black communities that had grown enormously in both size and population.7 Ten times as many blacks lived in Chicago in 1966 as in 1920. Representing but 4% of the city’s population in the latter year, blacks accounted for nearly 30% of all Chicagoans by the mid-1960s. The evolution of the West Side black colony, from enclave to ghetto, was a post-World War II development. And the South Side Black Belt’s expansion between 1945 and 1960 was so pronounced that its major business artery shifted a full 2 miles to the south, from 47th Street to 63rd.8

There is a chronological justification for referring to Chicago’s “second ghetto” as well. The period of rapid growth following World War II was the second such period in the city’s history. The first, coinciding with the Great Migration of southern blacks, encompassed the years between 1890 and 1930. Before 1900, the earliest identifiable black colony existed west of State Street and south of Harrison; an 1874 fire destroyed much of this section and resulted in the settlement’s reestablishment between 22nd and 31st streets. By the turn of the century, this nucleus had merged with other colonies to form the South Side Black Belt. Where, according to Thomas Philpott’s meticulously researched The Slum and the Ghetto, “no large, solidly Negro concentration existed” in Chicago until the 1890s, by 1900 the black population suffered an “extraordinary” degree of segregation and their residential confinement was “nearly complete.” Almost 3 miles long, but barely a quarter mile wide, Chicago’s South Side ghetto – neatly circumscribed on all sides by railroad tracks – had come into being.9

By 1920 the Black Belt extended roughly to 55th Street, between Wentworth and Cottage Grove avenues. Approximately 85% of the city’s nearly 110,000 blacks lived in this area. A second colony existed on the West Side between Austin, Washington Boulevard, California Avenue, and Morgan Street. More than 8,000 blacks, including some “scattered residents as far south as Twelfth Street,” lived here. Other minor black enclaves included the area around Ogden Park in Englewood, Morgan Park on the far South Side, separate settlements in Woodlawn and Hyde Park, and a growing community on the near North Side. Between 1910 and 1920 three additional colonies appeared in Lilydale (around 91st and State streets), near the South Chicago steel mills, and immediately east of Oakwood Cemetery between 67th and 71st streets.10

Ten years later it was possible to speak of an almost “solidly” black area from 22nd to 63rd streets, between Wentworth and Cottage Grove. Whole neighborhoods were now black where, according to Philpott, “only some buildings and some streets and blocks had been black earlier.” By 1930 even such gross measuring devices as census tracts documented a rigidly segregated ghetto. In 1920 there were no tracts that were even 90% black; the next census revealed that two-thirds of all black Chicagoans lived in such areas and 19% lived in “exclusively” (97.5% or more) black tracts. The West Side colony grew as well. Although it expanded only two blocks southward to Madison Street, it went from only 45% black to nearly all black in the same period; and a new colony appeared in an area previously occupied by Jews near Maxwell Street. By the time of the Depression, Black Chicago encompassed five times the territory it had occupied in 1900. Its borders were sharp and clear, it had reached maturity, and all future growth would spring from this base.11

The Depression, however, marked a relaxation in the pace of racial transition, in the growth of Chicago’s Black Belt. Black migration to the Windy City decreased dramatically, thus relieving the pressure placed on increasingly crowded Black Belt borders. The period of the 1930s, consequently, was an era of territorial consolidation for Chicago’s blacks. Over three-quarters of them lived in areas that were more than 90% black by 1940, and almost half lived in areas that were more than 98% black. On the eve of World War II, Chicago’s black population was, according to sociologist David Wallace, “very close to being as concentrated as it could get.”12

This meant that the 1930s and early 1940s produced only slight territorial additions to the Black Belt (such as the opening of the Washington Park Subdivision). Such stability provoked few black-white clashes, and a similar calm prevailed in the border areas surrounding the other enclaves. The colony in Englewood saw whites replace the few scattered blacks on its periphery, whereas its core around Ogden Park became increasingly black. The Morgan Park community grew in both numbers and area, but its population became virtually all black, and its expansion was accomplished through new construction on vacant land rather than the “invasion” of white territory. The Lilydale enclave followed the same pattern. The South Chicago and Oakwood settlements likewise grew in numbers but actually decreased in size as they became more solidly black.13 By 1940, St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton were able to assert that the Black Belt “had virtually ceased to expand.”14

The two decades between 1940 and 1960, and especially the fifteen years following the conclusion of World War II witnessed the renewal of massive black migration to Chicago and the overflowing of black population from established areas of residence grown too small, too old, and too decayed to hold old settlers and newcomers alike. It was during the 1940s and 1950s that the Black Belt’s boundaries, drawn during the Great Migration, were shattered. To the east, the Cottage Grove Avenue barrier – which had been buttressed by the activity of local improvement associations after the 1919 riot - fell as blacks entered the communities of Oakland, Kenwood, Hyde Park, and Woodlawn in large numbers. To the south and southwest, Park Manor and Englewood also witnessed the crumbling of what were, by 1945, traditional borders. On the West Side, the exodus of Jews from North Lawndale created a vacuum that was quickly filled by a housing-starved black population. The first new black settlement since the 1920s, the North Lawndale colony was the largest of several new black communities created in the post-World War II period.15

Every statistical measure confirmed that racial barriers that had been “successfully defended for a generation,” in Allan Spear’s words, were being overrun after World War II. The number of technically “mixed” census tracts increased from 135 to 204 between 1940 and 1950. The proportion of “non-Negroes” living in exclusively “non-Negro” tracts declined from 91.2% in 1940 to 84.1% in 1950, reversing a twenty-year trend. Moreover, of the city’s 935 census tracts, only 160 were without a single nonwhite resident in 1950; there were 350 such tracts just ten years earlier. Such startling figures prompted the Chicago Commission on Human Relations to hail them as signifying a reversal of the city’s march toward complete segregation. Their conclusion, however, was hastily drawn.16

The census figures for 1950 revealed not a city undergoing desegregation but one in the process of redefining racial borders after a period of relative stability. Black isolation was, in fact, increasing even as the Black Belt grew. Nearly 53% of the city’s blacks lived in exclusively black census tracts in 1950 compared with only 49.7% in 1940; more people moved into the Black Belt than were permitted to leave it. As overcrowded areas became more overcrowded, the pressure of sheer numbers forced some blacks into previously all-white areas. Thus, whereas blacks were becoming more isolated from the white population generally, a large number of whites found themselves living in technically “mixed” areas. Segregation was not ending. It had merely become time to work out a new geographical accommodation between the races.17

If, however, the territorial arrangement forged by the end of the 1920s needed revision, the postwar era provided, theoretically at least, an opportunity for dismantling, instead of expanding, the ghetto. That such a possibility existed has been obscured by the dreadful air of inevitability that permeated the ghetto studies produced in the 1960s and that sped analysis from the Stock Yards to Watts.18 Such telescopic vision blurred what occurred in between, placed an unfair measure of responsibility on those living in the World War I period for what later transpired, and provided absolution through neglect for those who came later. Indeed, the real tragedy surrounding the emergence of the modern ghetto is not that it has been inherited but that it has been periodically renewed and strengthened. Fresh decisions, not the mere acquiescence to old ones, reinforced and shaped the contemporary black metropolis.

Map 1. Percentage of black population, in census tracts, city of Chicago, 1940. (Source: U. S. Bureau of the Census, Population and Housing Characteristics, 1960.)

Map 2. Percentage of black population, in census tracts, city of Chicago, 1950. (Source: U. S. Bureau of the Census, Population and Housing Characteristics, 1960.)

Map 3. Percentage of black population, in census tracts, city of Chicago, 1960. (Source: U. S. Bureau of the Census, Population and Housing Characteristics, 1960.)

Certainly close observers of the housing situation in the years following World War II saw nothing inevitable about the continued expansion of preexisting ghetto areas. Robert C. Weaver, a member of the Mayor’s Committee on Race Relations and later the fi...