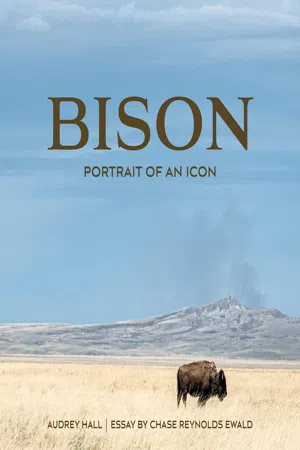

Audrey Hall | Chase Reynolds Ewald

John Heminway | Henry Real Bird

For my mother, Odete “Coco” Andren, who was willing to leave her country for a continued adventure in the American West. Her spirit and fortitude have always been both grounding and inspiring.

And for my father, Keith Willis Hall, an exceptional innovator who first introduced us to wild places, and who loved bison.

– A. H.

The American bison is thundering back into our consciousness a century after our thoughtless treatment nearly sent it into oblivion. Now a twenty-first-century renaissance of public awareness for this great animal—aided mightily by inspiring, artful books like this—is taking hold. Such celebrations make us feel better and unite us around a beloved emblem of the West. It reminds us how the undeniable rightness of restoring bison to public and private land can move us all toward a more meaningful relationship with Mother Earth.

—Todd Wilkinson, environmental journalist and author of Last Stand: Ted Turner’s Quest to Save a Troubled Planet

Foreword

There are two ways to admire a bison. The first is to marvel, maybe chuckle, at its size and lumbering gait. The other is to consider its tempestuous history—one that echoes the worst and best of humanity and leaves us spellbound when we learn how one enchanted creature overcame insuperable odds to survive.

While I am a member of both camps, these days I lean towards the second. Yes, I marvel at the girth and heft of the bison, but when seen in multiples, I measure bison in the infinite. If you have ever enjoyed the company of elephants and hummingbirds, you will look at bison not only for their singularity (reminiscent perhaps—after much squinting—of a wildebeest), but as icons of a continent, totems of the nineteenth century, and solemn admonishments to all of us inmates of the twenty-first century to do better.

As evidence of my many decades awestruck by the bison, I need only cast my eyes around my domestic surroundings. Some objects are subtle, even unobtrusive. Others make me stand back and relive the pleasure of their company. One object that surely will never fail to inspire me will be this book, as it takes its place alongside other objects that speak to the bison’s dazzling history.

Consider an oft-repeated legend that would seem pure hyperbole if it weren’t true: bison in North America once numbered in the many millions—some say sixty million. There were so many, in fact, that for one winter week in three Kansas counties their breaths formed a three-county storm cloud.

Oh, to have witnessed such a sight! Somewhere out in the far reaches of the Internet there must be a photo of those millions and the storm cloud aloft, but, so far, I have not seen it. The best I can offer is an oil painting I acquired during a book tour in Virginia in the ‘80s. Painted at the turn of the twentieth century by Canadian artist John Innis, it portrays bison forging ahead in winter. Even now it transports me as a study in animal grit.

Two rooms away, I note the hat holder my mother gave me when I was sixteen. Mounted on a rough pine board are three bison horns, in descending size. One can imagine they belonged to the same family, father, mother, and child, but that may be a stretch. On the back side of the board this inscription is carved: “Kiowa, Kansas, December 1889.” I can only imagine these bison were taken by a party of hunters, firing in quick succession, with the intention of feeding a banquet of men at Christmas. By all accounts, bison hunting was no great feat, given the quarry’s size and its predisposition to milling about in confusion as companions fell dead to either side. Even trai...