![]()

Chapter 1

What Is Wood?

A tree is just a big plant. When it’s a young sprout, a tree is like any other plant: soft and flexible. Like all plants, a tree is a collection of fibers. These thin, tough fibers are floppy by themselves, but when you bundle them together, they’re surprisingly strong. These fibers are hollow, and they carry water and nutrients up and down, so a plant is a like bundle of straws.

This green twig is flexible because the fibers are wet and soft.

This dead twig splinters instead of bending. Where it breaks, you can see the fibers that make up the wood.

Trees are different from other plants in one way: As the sprout grows into a tree, the middle fibers die and harden. The center of the tree stops circulating sap and turns stiff. The tree lives on, but all the functions of life happen just underneath the bark. The inside of the tree is dead, and these dead fibers are wood.

Even though wood can look smooth and solid, it’s just a bundle of straws. Everything we do to wood, from cutting it to finishing it, depends on these fibers, how they are laying, and where they are pointing. Remember this and you can do anything with a piece of wood.

Even though this log appears solid, it’s just a bundle of small, hollow tubes.

Why Make Things Out of Wood?

The modern world is filled with high-tech materials. Buildings are framed with steel beams. Our pots and pans are made from complex metal alloys. Even the bucket you use to wash your car is made from polyethylene, a material that didn’t exist a century ago.

When we’re surrounded by cheap and durable synthetics, wood might seem old fashioned, but it’s not. Humans have made things from wood for thousands of years, not just homes and furniture, but even wheels, tools, and dinner plates. For some things, wood was the only material available. For others, wood was—and still is—the best material possible.

These wooden spoons are just as good as anything you’d buy in a store, but because I made them myself, they fit my hand exactly.

Wood is easy to work and very durable. A wooden chest can last for centuries, even if it’s being used every day. Wood is light, but it can support a lot of weight, so it’s good for chairs and tables. Even more important, wood is pleasant. Plastic can feel cheap and metal feels cold, but wood feels warm and solid to the touch.

Wood is also ecologically responsible. Wood produces no toxic chemicals when it’s worked. Wood shavings can be used as garden mulch or composted to enrich the soil. Wood is biodegradable, and if you do throw it away, it breaks down like any other plant. And, while metals and plastics require huge amounts of energy to produce, wood makes itself. Trees just keep growing, so there will always be more. Many of the projects in this book can be made with reclaimed wood or green logs straight from the tree. When you rescue these pieces of wood from the dumpster or the side of the road, you keep them from being burned or landfilled, both of which release greenhouse gases. Using wood you find around the neighborhood reduces your carbon footprint, especially with the hand-tool methods we’re going to learn.

And while we might prefer a lightweight plastic bucket to an old-fashioned wooden one, tables, bookshelves, and chests work best in wood, which is a durable, lovely, and responsible material.

Strong and Weak

Because wood is a bundle of fibers, it has some surprising mechanical properties. Those individual fibers are extremely strong, but the bond between each fiber is pretty weak. So if we apply force along those fibers, wood holds up very well. If we put pressure between those fibers, they split apart.

Along the fibers, wood is very strong in compression and tension. If you stand a piece of wood upright, you can put a lot of weight on it and the wood won’t even bend. This is why big buildings can be made from wood. You can also suspend weight from a piece of wood, and like good rope, wood will easily bear the strain. Wood is also moderately strong perpendicular to the grain, so even a thin bookshelf will hold a lot of books, but if that shelf is longer than a couple of feet, it will bend in the middle.

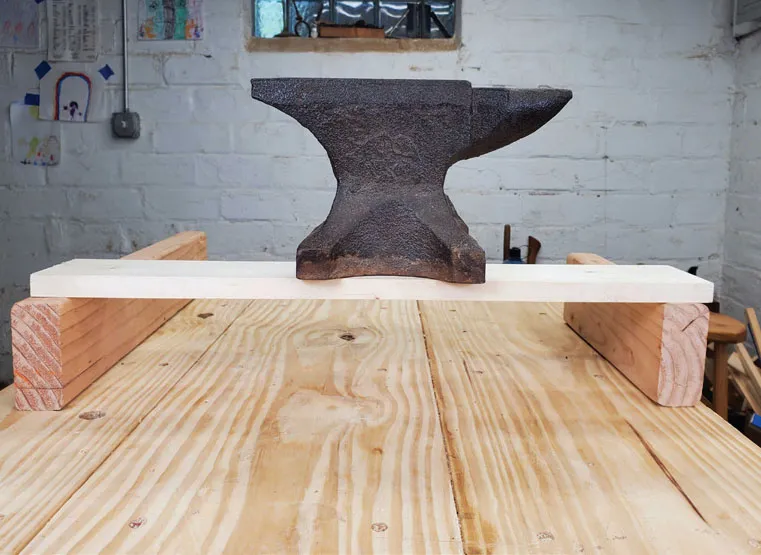

Even though this piece of wood is barely more than ½" (13 mm) square, it easily supports this 30-pound (14 kg) anvil.

This thin piece of soft white pine can support a lot of weight across the grain, but if it were much longer, it would sag.

For all its strength along the grain, wood is very weak across the grain (between the fibers). If you’ve ever split firewood, you know what I mean. Lay a log on its side and chop it hard with an ax. Even a sharp ax will barely penetrate. Now flip that same log up on end and chop down from the top. That log will split right in half.

Wood fibers are very strong. I swung this hatchet hard, but it barely dented the side of this log.

The bond between wood fibers is pretty weak. By chopping down into the end grain, the hatchet slid between the fibers and easily split this log in half.

This peculiar blend of strength and weakness makes wood an amazing material. When we understand wood’s strengths, we can build things that will last for decades. When we understand wood’s weaknesses, we can exploit them to make building easier. You might be surprised to find out that some of our projects will come straight from a log of firewood. Such a heavy chunk of wood might seem impossible to build with, but it’s pretty easy to knock a log into manageable pieces by splitting it along the grain. By understanding the structure of wood, we can save ourselves effort while still making strong projects.

Tip: As you’re reading these first chapters, take a trip to your local lumberyard or home improvement store. Just take a look at what woods they sell. What species are available? Is the wood dried?

Wood and Water

Wood is a living thing and when a tree is cut down, it’s filled with water. This water-logged wood is called green wood and some projects can be made directly with wet wood from the tree. Other projects need dry wood.

If you cut down a living tree, saw the trunk into boards and stack them outside, these boards will dry out until their water content equals about 12 percent of their weight. This process takes about a year and the resulting wood is called “air dried.” This wood is usually taken indoors, where conditions are warmer and drier, and dried for a few more weeks before it’s used.

This fresh-cut log is heavy and full of water. Some projects can be made from this “green” wood, but most furniture is made from boards that have been sawn and dried. The log is resting on a small piece of kiln-dried board.

In large-scale wood production, fresh-cut boards are placed in a kiln, a large metal container that uses heats and vacuum to physically pull water out of the wood. Kiln drying only takes a few weeks and can pull the moisture content of wood down to about 8 percent. If you buy wood in a store, it will probably be kiln dried.

But that’s not the end of the story. Wood keeps gaining and losing water long after the tree is dead. A piece of wood is always trying to be at equilibrium with its environment. In humid weather, wood absorbs water from the air. If the weather turns drier, wood will lose water. Wood and air are always trading water back and f...