- 75 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

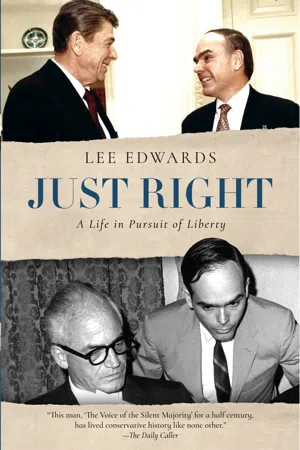

Lee Edwards has been an active player in the modern conservative movement longer than anyone else. As the Daily Caller noted in a recent profile, Edwards "has lived conservative history like none other." And he brings that history to life in Just Right. This memoir is full of colorful stories from a man who has done it all in a remarkable, multifaceted career. Just Right reveals:

- Edwards's inside account of Barry Goldwater's pivotal 1964 presidential campaign, for which he ran national publicity

- How he wrote the first political biography of Ronald Reagan—and discovered early on that Reagan was a secret intellectual who read Hayek, Bastiat, and Whittaker Chambers

- Why the New York Times dubbed Edwards "The 'Voice' of the Silent Majority"

- How he organized the largest public demonstration in support of our men in Vietnam

- How he created the Victims of Communism Memorial in Washington, pushing against the federal bureaucracy for two decades to make it happen

- In an inspiring chapter aimed at the rising generation, Dr.Edwards shows how conservatives can remain a major political and philosophical force in America.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

CRADLE CONSERVATIVE

I was born under the sign of FDR, on December 1, 1932, on the South Side of Chicago. I was the only child of Willard Ambrose Edwards, an award-winning, hard-drinking reporter for the Chicago Tribune, and Leila Mae Sullivan, the older daughter of the only Republican in the Irish American enclave of Bridgeport, within walking distance of Comiskey Park and the White Sox.

My father was a favorite of Colonel Robert R. McCormick, the imperious, mustached publisher and owner of the Tribune. In 1925, Dad’s first year at the Trib, the Colonel once visited the newsroom, leaving a nervous hush in his wake, and brushed by Dad seemingly without a glance. An assistant to the managing editor later imparted good news: “Your career is made! The Colonel asked who you were and remarked, ‘Nice-looking boy.’ ”

But it was my father’s way with words, not his Irish good looks, that secured his place in the paper. Confirmation of his status came in January 1935, when he was assigned to cover the most sensational story of the year and perhaps the decade—the Lindbergh baby murder trial. After the trial ended, my father was assigned to the Tribune’s Washington bureau. I was almost three when we rented a yellow stucco house in Silver Spring, Maryland, a sleepy suburb of seven thousand just across the D.C. line.

Beginning in the mid-’30s, Dad covered presidents from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Richard Nixon; presidential campaigns including Truman versus Dewey and the media-driven Kennedy-Nixon contest of 1960; every national convention, Democratic as well as Republican; and major congressional hearings, often scooping the Washington press corps, particularly in the early 1950s, when he was a confidant of Senator Joe McCarthy, a frequent guest in our home.

My father, Chicago Tribune reporter Willard Edwards (left), on the campaign trail with “Mr. Republican,” Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio

I did not attend public school until the second grade, a reflection of my mother’s skepticism about the progressive education of Montgomery County. I was bright but easily bored, with a temper I rarely bothered to control. At Montgomery Hills Junior High School, to which I bicycled every day, I learned some Latin and how to write an essay, was knocked out in my first football game and never played again, pitched softball tolerably well, and had a crush on our pretty young English teacher, who encouraged my writing and approved my appointment, at fourteen, as editor of the MoHiJuHi News, my first editorial post.

There were books in every room of our house—in the living room, in the dining room, in the bedrooms, in the bathrooms, everywhere. Dad preferred murder mysteries by Erle Stanley Garner and Rex Stout. Mom liked historical novels and could recite the kings and queens of England as easily as Dad could the chairmen of key congressional committees. They let me read whatever I wanted, and I soldiered through Kenneth Roberts’s tales of the American Revolution, cheering on the Rabble in Arms. I remember evenings when we would all be in the living room, each of us in a chair reading a book.

Mom practiced as well as talked politics. Appointed to the Montgomery County School Board—she had been a substitute English teacher during World War II—she ran for a full term on a “Back to Basics” platform. She would have won, I am sure, but the muckraker columnist Drew Pearson, who lived in the county, wrote a half dozen columns for a local newspaper about Leila Edwards, the “radical right” candidate and wife of Willard Edwards, reporter for the “ultra-conservative” Chicago Tribune and adviser to the “infamous” Senator Joseph McCarthy. It was the fall of 1954, and liberals had so traumatized the public about McCarthyism that Mom narrowly lost, the ironic victim of guilt by association, which liberals accused McCarthy of practicing. She never again sought public office.

Her bitter experience influenced my decision never to be a political candidate—my skin was not thick enough for electoral politics. My resolution was later hardened by my wife, Anne, who said, “I will divorce you if you run for office.” I told myself that Anne, a good Catholic, was bluffing, but I never tested her.

I enrolled at the all-male Bullis Prep School at the insistence of my mother, who would not let me go to Montgomery Blair High School, well known for its easy academics. I was poorly prepared for Bullis’s academic rigor—my first report card was all Cs and Ds. But the school taught me to think critically. I studied hard and by the end of the year was second in my class. I went on to edit the school newspaper, organize and lead Bullis’s first golf team, and score in the 98th percentile on the college entrance exams. In my senior year I won an award for all-around excellence. My years at Bullis strengthened my already evident self-confidence.

In my senior year, I applied to Amherst College in Massachusetts for the best of reasons: Bill Bonneville, my closest Bullis friend, was going there. I did not apply to any other school; in those days you did not send applications to a dozen colleges. To my shock, Amherst put me on its waiting list because, I surmised, of a poor grade in trigonometry—the rest of my grades were well above average. I decided I wanted nothing to do with the Ivy League and headed south to Duke University in North Carolina for the best of reasons: Duke had a winning golf team, and two of my golfing buddies had been accepted there. I learned later that Duke was a good university with exceptional teachers and a core curriculum.

I had won a four-year scholarship from the Chicago Tribune because of my scores on a college entrance exam administered by the University of Chicago. The scholarship provided $750 annually, which now sounds ridiculously low but covered most of tuition, room, and board at Duke in 1950–51. The total estimated cost, including books and laundry, was a low of $977 and a high of $1,185. That “high” would not cover the cost of one week at Duke today.

I had done so well on the ACE exam, scoring in the 98th percentile, that the University of Chicago said it would be happy to have me as one of its students. But it had no golf team, and my folks had long talked about the frigid winds coming off Lake Michigan and the snow almost as high as your waist. I declined the invitation. Among the professors under whom I might have studied were Richard Weaver, Milton Friedman, and F. A. Hayek. My high scores were not a true reflection of my intelligence—my IQ was under 130—but the product of the monthly ACE drills at Bullis.

JOURNALISM AND ANTICOMMUNISM

At Duke I joined the campus paper, the Duke Chronicle. I spent every Thursday evening, and then Tuesday evening when the paper became a biweekly, working my way up the editorial ladder. In my junior year I was one of two candidates for editor but lost to my prime rival, Bill Duke, no relation to the founder of the university. Bill was a better editor but I was the better writer.

In my senior year I became the founding editor of the Duke Peer, a new feature magazine. We attracted little campus attention until we profiled Senator Joe McCarthy with the title “Nice Guy or Demagogue?” It was early 1954, and according to liberals America was in the middle of a Reign of Terror engineered by Senator McCarthy.

I assigned the article to our associate editor, Connie Mueller, asking only that she write what she learned from her own research and draw her own conclusions. Without any coaching from me, Connie concluded that McCarthy was not a reckless demagogue but rather a patriot who would brook no compromise in “his main purpose of fighting ‘the Red Menace.’ ” Studying the record and especially the press coverage of the senator, Connie wrote, “Clearly, Joseph Raymond McCarthy . . . has been the subject of vigorous character distortion by an opinionated press.”

McCarthy had been front-page news since February 1950, when he made his famous Wheeling, West Virginia, speech (“I have here in my hand . . .”). Since then, my father had had almost unrestricted access to the senator and his top aides and investigators. It was the biggest running story of his career.

My first impression of Joe—he encouraged you to call him by his first name—was that of a shoulder-squeezing, joke-telling politician who drank but not any more than the average Irishman. He was serious about one thing—communism. When challenged about something he said about the communist menace, he would fix you with his dark Gaelic eyes and say in his deep rumbling voice, “You’re either with me or against me. You’re either with me or the communists. Which is it?” He was spontaneous, incapable of leading a conspiracy, because that would have required detailed planning and constant scrutiny.

His unbridled passion to expose the communists in our government inspired people by the millions. My mother, who was a volunteer in his office, wrote me that “never have I seen such devotion. The stenographers, the secretaries, the investigators, all of them working 16 hours a day.” But don’t expect any thank-you or recognition of your sacrifice from Joe, she said. “He eats, sleeps, and lives his crusade. His whole conversation is what to do next to further ‘cleaning out the subversives.’ ”

Joe could be mischievous. One day, he and Dad were scheduled to have lunch in the Senate dining room. As they stood in the reception room of his office, Joe said, “Wait a minute,” and walked into an adjacent room in which a half dozen volunteers were seated around a long worktable, opening and sorting the hundreds of letters he received every day. Many contained rosaries, prayer cards, coins and bills, even a Social Security check. Joe picked out a $20 bill and said, smiling, “That ought to cover our lunch.”

In the spring of 1954, along with millions of Americans, I watched the televised Army-McCarthy hearings and despaired as Joe tried to turn back the phalanx of the Establishment. Public support plummeted. In December he was condemned by the U.S. Senate, with all Democrats voting for censure and Republicans evenly splitting. Barry Goldwater, one of McCarthy’s strongest defenders in the Senate debate, voted no.

McCarthy’s censure was a pivotal event in the early history of the conservative movement. Liberals invariably described it as a crushing defeat for conservatism. But in fact it hardened William F. Buckley Jr.’s resolve to launch National Review the following year, and it inspired the formation in 1958 of the John Birch Society, a major if controversial player in the movement. Conservatives did not abandon anticommunism but resolved to prove wrong Nikita Khrushchev’s boast that “your grandchildren will live under communism.”

Five decades later, McCarthy’s claims about the number of subversives in our government were conclusively shown to be not inflated but understated. In Blacklisted by History: The Untold Story of Senator Joe McCarthy and His Fight Against America’s Enemies (2006), Stan Evans documented hundreds of communists and other security risks in official Washington during the 1930s and 1940s—double or perhaps triple McCarthy’s estimates. Stan provided thirty-one pages of endnotes and a lengthy appendix plus dozens of FBI and other government documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. He concluded that “the Red network reached into virtually every important aspect of the U.S. government, up to very high levels, the State Department notably included.”

MY OWN PATH

I enjoyed meeting power men like Joe McCarthy and Richard Nixon, who was a guest in our home, and I felt the pull of Washington, the most powerful city in the most powerful country in the world. But in my senior year at Duke, I decided that political writing was not for me. I determined to enter the Army as an enlisted man and then to live in Europe, probably in Paris, and write the Great American Novel. There was another reason for my eschewing political writing: I did not want to be compared with my father, knowing I would always come in second. Living 3,828 miles away from him seemed about right.

Private Lee Edwards, U.S. Army, 1954

2

PARIS HOLIDAY

In the fall of 1956, I was living on the Left Bank of Paris, attending classes at the Sorbonne now and again, trying to write a novel, and becoming a habitué at Le Select and other Montparnasse hangouts. I was two months removed from my honorable discharge from the U.S. Army after a year and a half of soft duty in Heidelberg in the Signal Corps and sixty days of temporary duty entertaining the troops in EM and USO clubs in France and Germany. I was pursuing as hedonistic a life as is possible on a monthly stipend of $125 from the GI Bill. I grew a Vandyke, smoked Gauloises, drank Algerian red, read Ernest Hemingway and Henry Miller, and was admitted without ceremony into the American expatriate community. I paid little attention to politics.

My agreeable little world exploded on October 23 when the students of Budapest—young men and women in their early twenties like me—ignited a revolution against the Hungarian People’s Republic and its Soviet protectors. The streets filled with thousands of demonstrators demanding the dissolution of the communist government and free elections. They defiantly sang the Hungarian national anthem—“This we swear, this we swear, that we will no longer be slaves.”

A thirty-two-foot-high bronze statue of Stalin was toppled. The hammer and sickle was cut out of the middle of the Hungarian flag, and the Flag with a Hole became a symbol of the revolution. In the face of the militant uprising, Soviet troops pulled out of Budapest, retreating into the countryside, and a new people’s government was formed.

I was ecstatic. The French newspapers carried banner headlines like “Hongrie Libre.” The radio resonated with the triumphant voices of the young revolutionaries who were sending packing the most powerful army in the world. Communism seemed to be toppling.

My dormant anticommunism came alive. All that I had learned from my reporter-father, who had covered congressional hearings about communism, came flooding back. I remembered reading his stories about show trials, firing squads, and Siberian exile, of those who had survived the KGB and the Gulag, of Americans who had willingly betrayed their country for a greater revolution, the Bolshevik Revolution.

Ex-communists like Freda Utley and Ben Mandel had explained to me the base treachery of the August 1939 Hitler-Stalin pact that started World War II. Alger Hiss, the golden boy of the liberal establishment, had been a Soviet spy in the 1930s and during World War II. Senator Joe McCarthy was right—there had been dozens of communists in our government, and at the highest levels. Now, caught up in the sights and sounds of a jubilant Budapest celebrating its freedom, I thought: How the Politburo in Moscow must be shaking in their Stalinist boots.

I put aside Baudelaire and Colette and devoured Le Monde and Le Figaro for the latest news. The new Hungarian government, headed by the reformer Imre Nagy, promised fundamental political change and said that Hungary would withdraw from the Warsaw Pact. My God, I remember thinking, we could be watching the unraveling of the Soviet Empire.

That Moscow was th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Prologue: Dedication

- 1 Cradle Conservative

- 2 Paris Holiday

- 3 The Movement

- 4 Rebels with a Cause

- 5 Reluctant Champion

- 6 The Day Kennedy Died

- 7 Decision Time

- 8 A Choice, Not an Echo

- 9 The Real Barry Goldwater

- 10 The Must Primary

- 11 Civil Rights and the Constitution

- 12 Convention

- 13 Things That Matter

- 14 Extremism and Liberty

- 15 Anything Goes

- 16 Let Goldwater Be Goldwater

- 17 Landslide

- 18 27 Million Americans Can’t Be Wrong

- 19 On My Own

- 20 Author, Author

- 21 The “Voice” of the Silent Majority

- 22 Square Power

- 23 The Rabbi and the President

- 24 The New Right

- 25 The Changing Face of Conservatism

- 26 Captive Nations and Peoples

- 27 Leaving the Arena

- 28 Back to School

- 29 Defalcation

- 30 Missionaries for Freedom

- 31 “Dear Bill”

- 32 The Making of a Memorial

- 33 The Final Step

- 34 Dedication Day

- 35 Chimera?

- 36 Trumped

- 37 Coda

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- Copyright Page

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Just Right by Lee Edwards in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.