![]()

CHAPTER 1

IRON

The J. Edgar Thomson steel plant was the finest in Pittsburgh, probably in the world, and its superintendent, Captain William Richard Jones, was the country’s most celebrated steel man. He ran an efficient plant, the pride of the Carnegie Empire. The short, tough, fifty-year-old superintendent had worked his way through the ranks, starting as a machinist’s mate at age ten. He had enlisted as a private in the Union army during the Civil War and earned a battlefield commission to captain. Now, he managed the steel industry’s largest mill.

One Thursday evening, September 26, 1889, six of the plant’s seven furnaces were humming. Day and night, J. Edgar Thomson pounded out record output under Jones’s firm hand. The second shift had gone smoothly—except that damned Furnace C. It had been acting up all day.

“Cap’n, come quick! Mr. Gayley needs you,” yelped a sweaty laborer.

Jones did not tolerate production snags, whether caused by man or machine. Getting into the action was part of the job. “Let me take a look,” he grunted. A clump of slag and coke had blocked the furnace like a flotsam and jetsam of logs damming the flow of a river. The team had to react quickly to avoid an explosion from the building pressure.

Sparks flew and the furnace roared as the men tapped the line with a sledgehammer to reduce pressure. “Keep at it,” exhorted an impatient Jones.

“Shit, it ain’t tapping,” shouted a Hungarian laborer, pounding furiously at the metal rod held in place by worker Michael King. “We’re in trouble. Pressure’s a buildin’ fast!” The struggling workers stepped aside to let Jones take a look.

Jones entered the fray with the same intensity he had demonstrated as an officer with the Eighty-Seventh Pennsylvania Volunteers at Chancellorsville and Fredericksburg. He grabbed the hammer from the Hungarian laborer and swung with all his strength to attack the blockage.

Without warning, a one-foot metal sheet just above Jones’s head flew from the furnace, spraying a deadly wave of cinder ash and molten steel. The onrush encased the unfortunate Hungarian laborer in a steel ingot. His body would not be discovered until the following day. Michael King dissolved, boiled in a lava flow of steam, buried in a shipment of rails. The wall of liquid death showered Jones in a bath of molten steel, scalding his face and hands.

Jones leapt for safety, but he struck his skull on a nearby rail car. The team reacted swiftly. A foreman shut down the blast to the furnace, halting the hail of flames and fire—too late. A nearby worker dragged the semicomatose Jones to the safety of an empty room, where a physician treated his burns and summoned a gurney. Jones moaned incoherently. He never regained consciousness and died in the Homeopathic Hospital three days later.

Thousands attended the superintendent’s funeral on October 2. The “Cap’n,” as the men called him, had been no ordinary manager. He got his hands dirty and knew steel. He would chip in when the going got tough, and that’s what killed him. “He could be a bastard, tough, ornery and mean, but at least he was our bastard,” spouted one worker, summarizing the general feelings of the plant. “Kelly, one of the two others killed in the accident, had been a good Mick, but now a dead one,” eulogized another worker. “There but for the grace of God lay I, on my back in a pine coffin,” thought another laborer as he cocooned in the safety of his row house after the funeral.

Carnegie Steel executives Henry Clay Frick and Andrew Carnegie served as honorary pallbearers, although Jones had liked neither man. Workers from the plant escorted the coffin to what is now called Homewood Cemetery.

Only family and close friends would mourn the laborers, Michael King and the nameless Hungarian. Carnegie could easily replace an unskilled worker with another hungry body, but Jones’s death proved downright inconvenient for the team at Carnegie Steel. He had been an asset who drove plant production to record levels and developed dozens of valuable patents, including a “Feeding Apparatus for Rolling Mills,” an “Apparatus for Removing and Setting Rolls” and a “Hot Bed for Bending Rails.” The “Mixer” Jones invented combined several steps in the manufacturing process, saving hundreds of thousands of dollars while providing J. Edgar Thomson with a distinct competitive advantage over its rivals.

The day after the funeral, the pony-sized bundle of nerves Henry Phipps, a Carnegie partner and financial officer, accompanied by Henry Curry, the plant’s furnace supervisor, knocked on widow Harriet Jones’s door, hat in hand. The executives ostensibly came to offer their condolences, but they had an ulterior mission. Phipps carefully explained how all patents filed on company time belonged to Carnegie Steel. He glanced toward a picture of Captain William Jones in his Civil War uniform on the mantel before shifting his gaze. A tear formed on the widow’s cheek, and Phipps felt a twinge of sympathy. Harriet Jones already had lost two of her four children at an early age and now a husband. Phipps continued, “As a reward for your husband’s years of service and his unfortunate untimely death, the company graciously is offering a lump-sum settlement of $35,000, provided you sign over all Captain Jones’s patents.” Harriet Jones knew $35,000 represented a fortune, and possibly a fair price, even though her husband had earned the unheard-of salary of $25,000 per year. The amount offered would feed and clothe her family for as long as she lived. The grieving widow signed the document without objection, anxious to have these men go and grateful for the money.

Henry Phipps raised himself from a chair to his full five-foot, three-inch height, took leave of the widow and departed the house with a complacent smile. Jones was dead, the widow was paid and Phipps and Curry had recovered the invaluable patents for a fraction of their value. Steelmaking at the plant would continue without disruption, and Carnegie Steel’s immense profits would continue.

•••••

The iron and steel industry dominated the economy of nineteenth-century Pittsburgh. In the last quarter of the era, the J. Edgar Thomson plant under the leadership of Captain Jones dwarfed the competition. While metal production served as the primary impetus for the city’s progress and wealth, heavy industry delivered horrible side effects. The noxious stink, searing heat and noise from the mill sucked the common laborer dry. Writer Hamlin Garland described the city of Pittsburgh, home to several of the country’s leading iron and steel mills, as like “looking into hell with the lid taken off.”1

The loud click-clack of horse-drawn wagons against cobblestone, the hammer striking the blacksmith’s anvil and the shouts of street vendors hawking wares intermingled with the whinny of horses and the snap of a whip, generating a cacophony of noise. The smells were worse. Scraggly chickens clucked and wild pigs oinked while covering the axle-rutted byways with disease-ridden feces. Pigeons blackened the skies and dropped excrement below them, spreading their own pestilence. A single large horse expelled twenty-four pounds of dung daily, attracting rats, flies and other noxious vermin. A decomposing horse carcass might rot unattended for days on the dirt streets until carted away by the authorities or its owner.

Without sewers and running water, disease from the streets ran rampant. Families tracked contagion into their homes on the bottoms of their shoes. April rains splattered the mess into basements, delivering a lethal dose of germs. Pittsburgh’s winter slush and drafty rooms brought pneumonia, flu and bronchitis. Summer carried its own horrors. Local markets hawked rancid squirrel, rotting hog and week-old venison. Spoiled meat and the metallic tang of factory waste permeated the dinner table. A diet low in fruits and vegetables led to an unhealthy lifestyle. Hundreds died from cholera, diphtheria, dysentery, tuberculosis and plague. The scourge of bad food, tainted water and the resultant diseases assailed rich and poor alike. Fanny Jones, a niece of iron baron Ben Franklin Jones and the fiancée of wealthy banker Andrew Mellon, succumbed to tuberculosis in her twenties. Even mighty Andrew Carnegie barely survived a bout with cholera.

Hamlin Garland also described the steel town of Homestead, a typical mill city located a few miles from Pittsburgh: “The streets were horrible; the buildings poor; the sidewalks were sunken and full of holes; and the crossings were formed of sharp-edged stones like rocks in a riverbed. Everywhere the yellow mud of the streets lay kneaded into sticky masses, through which groups of pale, lean men slouched in faded garments, grimy with the soot and dirt of the mills.”2

Management displayed a callous neglect for safety. The filth and danger at the mills proved even more pernicious than that encountered on the surrounding streets. Scalding water leaked from the ceiling pipes and oozed onto the floors below. Men either learned to dodge the sizzling steam or bore reminders of it for a lifetime. Iron making was dangerous, but the advent of steel would magnify the risk many fold. Ladles of molten metal swung precariously from chains, threatening instant eternity. Crushed limbs and broken bones occurred daily due to tools dropping, slips, falls and malfunctioning equipment. In one single year in the late nineteenth century, 195 industrial accidents in western Pennsylvania culminated in death.

After a long day’s work in this treacherous environment, weary Hunkies, Poles, Slavs and Wops, as their Western European bosses pejoratively called them, found solace from their drudgery and danger in saloons. The more vocal, emboldened with a shot or two of whiskey and a beer chaser, might hatch plans for unionization. The common laborer struggled to eke out a living. “We work like dogs and get paid like whores,” bellyached a Slav in broken English—a brave militant when far from the earshot of the bosses.

The average immigrant laborer lived in ramshackle housing. Single men crowded in rented rooms or lived with family. Few homes had running water. Wives and mothers dragged drinking and bath water from the Monongahela, the same river where the mills dumped their industrial waste. Families routinely bathed in the chilly Allegheny and Monongahela before city council outlawed the practice. Laborers from iron manufacturer Jones and Laughlin squeezed into South Side areas like Hunky Hollow and Painter’s Row, which contained five hundred sardine-sized dwellings, most with no lawn and only a rudimentary cellar kitchen. Other workers lived in Allegheny City, now a part of Pittsburgh and home to Heinz Field and PNC Park. Braddock and Homestead contained their own overcrowded row houses. The location made little difference—slums were slums.

Coal miners in nearby Connellsville, the immigrant grunts who supplied the basic ingredient for the coke used as fuel, fared even worse than mill hands. Those lucky enough to survive the trauma of cave-ins and mine explosions died young from black lung disease, overwork or poverty. Some unscrupulous owners cheated these workers. With wage rates based on coal weight, managers might count 2,100 pounds as a ton. Miners frequently found themselves short of cash. Employee stores provided credit but charged usurious rates for basic necessities like flour and salt. Money-hungry owners forced workers to sign yellow-dog contracts, a pledge not to join unions or face the penalty of an immediate loss of job.

Writer Garland described the dehumanization of mill and mine life: “The worst part is that it brutalizes a man. You start to be a man, but you become more and more a machine. It’s like any severe labor, it drags you down mentally and morally just as it does physically.”3 “No wonder we pray to Our Lady of Sorrows,” complained one Slovak wife.

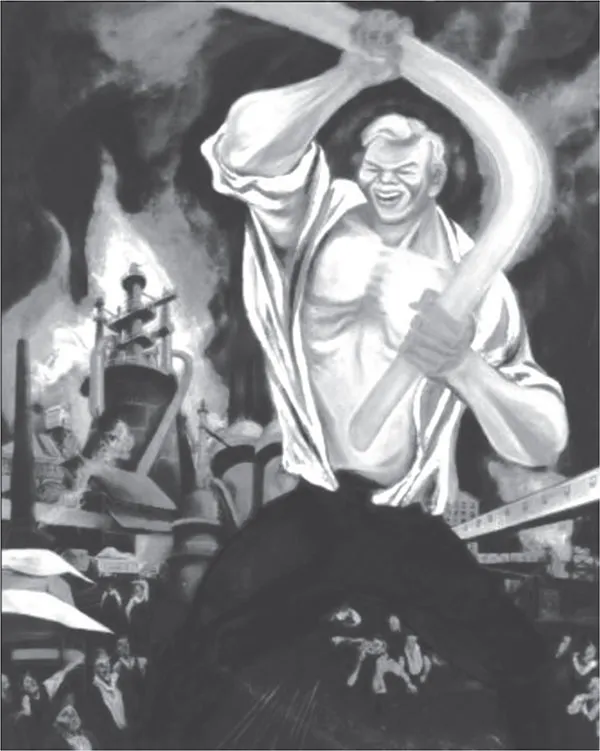

As a response to the horrors in the mills, the iron and steelworkers invented the mythical hero Joe Magarac, cousin to Paul Bunyan, the logger hero who rode the giant ox Babe. With his narrow waist, thick chest, calloused hands and muscled biceps, Magarac personified the physical strength required to survive in the steel mill:

Joe Magarac could bend steel rails with his bare hands.

Born out of Braddock, earth, rock and hill, king of the ingots, pride of the mill, nothing about him was timid or small. He gathered the scrap iron, the limestone, the ore; fanned the white heat to an angry red roar.

He poured liquid fire in an ingot mold, and taking a handful before it got cold, he squeezed through his fingers and watched it congeal from taffy-like ribbons to straight rails of steel. Best steelmaker in the land, steel-heart Magarac, that’s the man.4

Like their mythical counterpart Joe Magarac, Pittsburgh’s unlettered iron and coal workers had fled their villages and towns in search of a brighter future in America. Ukrainian farmboys avoided conscription and death in the Russian army by hiding beneath wagons of hay headed for port cities like Odessa. Hungarians, Poles, Serbs, Slavs and Croats likewise fled the Old World in search of greater opportunity in America. With a few kopecks in their pockets, they bought third-class passage on tramp steamers or sailing crafts headed to New York. Stuffed like sardines in cargo holds, these brave souls battled scurvy, storms, high waves and disease. Somehow, this hodgepodge of humanity reached the final leg to Pittsburgh.

Few Eastern European immigrants spoke much English, placing them at a distinct disadvantage. As Catholics in a Protestant-dominant industry, they met up with a heavy dose of prejudice in an industry run by their British and German bosses. Heavy accents and limited communication skills doomed most to bare subsistence jobs without promotion—cleaning floors, hauling slag and scrap and loading ore, limestone and coke into the furnaces. Complaints served no useful purpose. Only acceptance and the ability to learn the language of steelmaking might vault the occasional worker toward advancement at higher pay.

These dispirited men trekked six days a week across the bumpy paths between the crowded ghettos they called home and the mill. Long twelve-hour shifts and hazardous work provided the possibility, even the probability, for injuries. Tired men make mistakes, and iron and steelmaking extracted a fierce price. Few who worked in the iron and steel industry survived past sixty. Since unskilled labor earned seven dollars per week or less, those with wives and children faced a life of meager subsistence. A better-paid skilled tradesman might skimp and save to squirrel away enough to buy a small house. The unskilled continued in rented rooms or, even worse, lost their jobs through ill health, injury, union activity, technological displacement or just plain bad luck.

Day after day, the roar of the furnace, the clang of chains, the pounding of the trip hammer slamming against an anvil, the thud of ore pouring into the hopper and the hiss of steam buffeted the ears of the workers. Smoke, heat and the acerbic stink of sulfur assaulted their noses. The glare of the blow during conversion and the haze that followed burned their eyes.

Like the fiery conversion of pig iron into steel through beating and heating, the country bumpkins who entered the mill soon found themselves tempered into hard metal. Survival required quick reflexes, strength and thick skin. Those who entered as boys quickly hardened as men. Numbness, only numbness, made mill life tolerable. At workday’s end, the married man might flee the clatter of the mill to seek solace in the quiet warmth of his house, a loving wife and possibly the adulation of an adoring son or daughter. The laborer without family might seek escape by wasting his hard-earned dollars in the seedy bars or brothels surrounding the plant. The pressure from a real or imagined insult often exploded like a Bessemer heat into a fight. It mattered little who won or lost because the next day the combatants would return to the hell of steel for another bout with the devil.

On Sundays, the godly attended Latin Mass at St. Thomas in Braddock and thanked Jesus for the blessings of the past week, a family, a roof over their heads and enough to eat. The most ambitious learned to read English but, more importantly, encouraged their children to go to school. Natural curiosity allowed the lucky few to advance to positions like senior smelter or furnace attendant, but these proved the exception. All prayed for a better life for their children.

In juxtaposition to the workforce, the bosses lived a privileged life, their bellies filled with beef, potatoes and fresh milk. Ketchup, mustard, pickled onions and sauerkraut, all made in Pittsburgh, most courtesy of local purveyor Henry Heinz, added spice to their tables. Decked out in top hats and fancy suits, the steel barons paraded about Pittsburgh.

The bosses were different than the working folk—not just richer. They weren’t necessarily evil men, just men who lacked sentiment and pursued the dollar regardless of the consequences. They considered labor a mere tool, a shovel to hoist cinder ash, to be discarded when the blade cracked or the handle broke, thrown aside like useless slag.

The early iron and steel bosses such as Ben Franklin Jones, Andrew Carnegie, Henry Oliver and Henry Phipps subscribed to the theory of manifest destiny, that God ordained them with what philosopher Max Weber called the “Protestant Ethic.” Material accumulation in this life pointed to a future place in heaven. American capitalism developed hand in hand with John Calvin’s teaching of predestination. Metal-monger B.F. Jones assumed the Almighty not only justified his pursuit of wealth but pronounced it a virtual commandment. The hand of the divine touched those who prospered. When asked how he obtained his wealth, Cleveland multimillionaire John D. Rockefeller proudly proclaimed, “God gave me my money.”5 Popular songs crooned the tune of material achievement. The nineteenth-century rich mouthed the words of the song “D...