eBook - ePub

W. H. Auden

In the Autumn of the Age of Anxiety

Alan Levy

This is a test

Share book

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

W. H. Auden

In the Autumn of the Age of Anxiety

Alan Levy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

W. H. Auden takes you to Auden's home in Austria to ask him questions; the conversation on the lawn that one dreams of. A fine tribute." — Bestseller

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is W. H. Auden an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access W. H. Auden by Alan Levy in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The Permanent PressYear

2015ISBN

9781504023337

1

THE MAN: AFTERNOONS ON AUDENSTRASSE

“Follow, poet, follow right

To the bottom of the night,

With your unconstraining voice

Still persuade us to rejoice;”

Scene 1: | IN KIRCHSTETTEN 1971 |

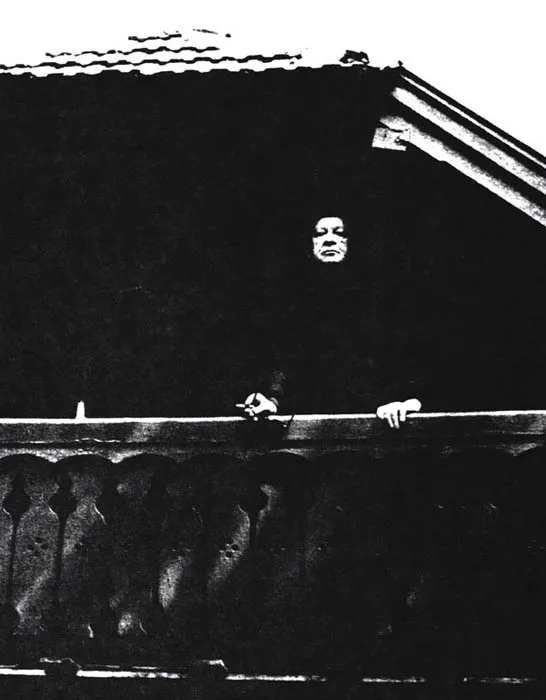

Kirchstetten is where one might have expected Robert Frost to live on a Guggenheim: an Austrian village of 800 with red-shingled roofs glistening in the cool but benign noonday sun; neat green and brown fields lying fertile and fallow as though ordained by an almanac. The local train from Vienna—a rickety, green Third Avenue El retread with iron-gated open platforms—hews to its schedule, too: precisely 54 minutes from the Wien Westbahnhof to Kirchstetten. Rising from the platform’s lone bench, the tall man in the red sport shirt, worn loose and flowing like a body bandana over baggy khakis, checks the train’s arrival against his wristwatch and nods approvingly. Then his creased face—which has been described as “grooved and rutted like a relief map of the Balkans” and which he himself once said looked as if “it had been left out in the rain” too long—furrows further while his watery eyes squint and canvass the train to ascertain if the visitor who invited himself down is indeed aboard. Only when the sole disembarking passenger in city clothes marches directly toward him does the face re-fold itself into a smile and W. H. Auden rises to extend a brisk handshake of welcome.

“We have to hurry because lunch is in fifteen minutes,” he says, ushering his guest toward a creamy Volkswagen. This slave to the clock needs no further introduction on the station platform, for the world recognizes him as the bard who named our times “The Age of Anxiety” and won the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for his long poem of the same name set in a New York bar. This is the poet who pleaded—in a poem called “September 1, 1939,” which he later withdrew from circulation—that “we must love one another or die.” This is the heir wearing, somewhat reticently, the mantle of Yeats and Eliot. Jacques Barzun praised him as “the greatest living poet in English” and the more prosaic New York Daily News touted him as “a classic in his own lifetime.”

This is also the British-born, naturalized American son-in-law of Thomas Mann and casual widower of Mann’s dark-haired, dark-eyed daughter Erika. This is the former partner of the novelist Christopher Isherwood and, for a good two decades, part-time partner of the opera librettist Chester Simon Kallman. But, right now in 1971, this is Wystan Hugh Auden, 64, long-time resident of St. Mark’s Place in the East Village who spends April through October in rural Austria. He calls Kirchstetten “a chapter in my life which is not yet finished,” though he will, before long, forsake Manhattan and indeed end his days in Austria.

“I first beheld Kirchstetten

on a pouring wet

October day in a year

that changed our cosmos,

the annus mirabilis

when Parity fell.”

“That was 1957,” Auden explains, “a rather important year in the history of physics—when it was discovered that all physical reactions are not symmetrical.” He came here more than a decade after the end of World War II freed him from Fire Island summers—when the shabby volcanic Italian isle of Ischia grew “altogether too expensive and touristy. That will never happen here: Kirchstetten has no beaches, no skiing, no hotels and no tourists.”

Speaking in British cadences (though occasional Americanisms creep in: “I was brought up to say grahss, but now I say graass”), Auden’s bass voice resonates with Oxonian certainty even though the rumble of the Autobahn a half-mile away means anything can yet happen.

For now, however, he is secure in the two-story, shingled, two-tone green farmhouse which, along with three acres of land he bought for $10,000 “soon after the Russians had left, when everything was cheap and very run down and hardly anybody here had cash. I had dollars, so I was able to beat out a theater director who was after the same property.”

It is a quiet life that Auden lives here once he puts the anarchy of the city and the publishing world behind him. In the insular, caste-conscious Austrian provincial society, Auden is an Ausländer (foreigner), a Herr Professor (Smith, Swarthmore, Oxford, etc.) and sometimes Herr Dichter (Mr. Poet). This, by definition, means that the only Kirchstetten Inländers with whom he can associate socially are “the schoolmaster and his wife, the doctor and his wife, and the new priest—a young man whose name is Schickelgruber!* I’ve recently introduced Father Schickelgruber to his first martini. It was a huge success.

“Some Viennese friends briefed us on the system soon after we arrived here. For example, I’m on very good terms with the local Bürgermeister (Mayor), but I’ve never invited him over for dinner. For all his qualifications, he doesn’t have a degree and one doesn’t know whether or not he’d accept, but one does know he’d be embarrassed.”

A steady, careful driver, Auden follows the direction of a varnished rustic wooden marker pointing toward Weinheberplatz, named after a poet who collaborated with the Nazis and took an overdose of sleeping pills when the Russians came. In a poem of his own called “Joseph Weinheber (1892-1945),” Auden wrote:

Reaching my gate, a narrow

lane from the village

passes on into a wood:

when I walk that way

it seems befitting to stop

and look through the fence

of your garden where (under

the circumstances they had to)

they buried you like a loved

old family dog.

And now Weinheber’s grave is covered with weeds, but Auden is still affected by the tangible presence of a “poet I’d never heard of until I came here.” For the 20th anniversary of Weinheber’s death, Auden wrote:

Categorized enemies

twenty years ago,

now next-door neighbours, we might

have become good friends

sharing a common ambit

and love of the Word,

over a golden Kremser

had many a long

language on syntax, commas

versification.

Near Weinheberplatz, Auden swerves down a side road with a smaller marker that says Audenstrasse. Only when the visitor remarks on it does Auden say, with unfeigned embarrassment: “The Gemeinde (township) really shouldn’t have done it. I don’t have the bad manners to tell them how much I detest it, but I don’t have the nerve to thank them for it either. The name Hinterholz is so much better.” The sign on his garden gate and the print on his stationery both identify Hinterholz, not Audenstrasse, as the street where he lives.

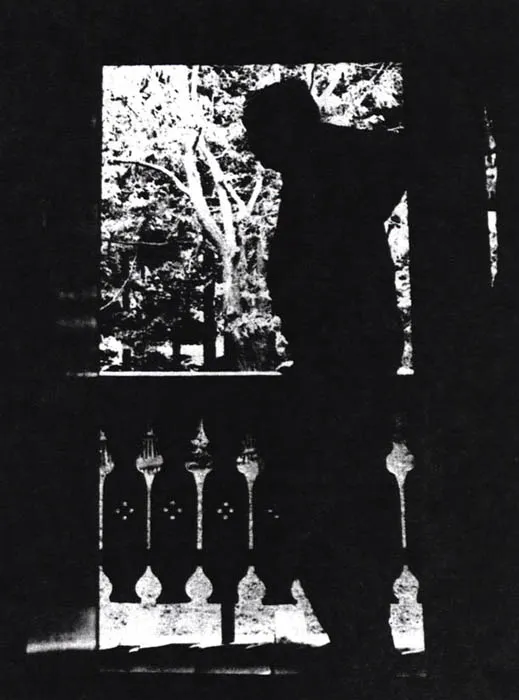

It is seconds before 1 P.M. when Auden drives inside a square concrete garage. Then, wheezing slightly with exertion, he leads his visitor up a steep footpath to the set-back farmhouse which is almost invisible from below. Metal garden furniture is arranged informally (and, thus, in a highly un-Austrian manner) on the front lawn. Auden seats his guest before going inside “to tell Chester we’re here and to fetch the Bloody Marys.” The host returns, after a few minutes, with a dish of pistachio nuts and a crossword puzzle, which he will fill in during lulls in the cocktail conversation.

Not that Auden is anything less than an ardent conversationalist. Any dialogue with Auden is a two-way street. He listens attentively and, sometimes much later, will take you up on something you said to him before. He anticipates what you were about to say and even mouths your lines, usually quite accurately, but he doesn’t speak them. If your punch line comes out all right—that is, the way he anticipated—his eyes flash an unspoken signal of well done! But when you cross him up, he either crinkles with delighted surprise or puckers with disappointment. Again, though, both reactions go unsaid.

“The drinks will be out shortly. Chester is still preparing lunch,” Auden reports, looking relieved at not having disrupted a schedule. “And do you happen to know a four-letter word meaning ‘first name of Swoboda and Hunt’?” His guests supplies Rons. Auden asks: “What are they? Statesmen?” No, ballplayers. Auden moans over American crosswords; he prefers London’s Sunday puzzles and, besides, “the Americans are so inaccurate—for example, a five-letter word for ‘irreligious person’; answer: ‘pagan’! But if the pagans were anything, they were over-religious.”

In rapid-fire conversation, I learn that “I DETEST AUNTS” is an anagram for “UNITED STATES”; “CINERAMA” is an anagram for “AMERICAN”; and “WHY SHUN A NUDE TAG” is “WYSTAN HUGH AUDEN.” For Auden is indeed, as he told Weinheber in verse, a lover of the Word—but of the written Word and of the Word spoken face-to-face. In Kirchstetten, he lives without telephone and television:

“I do have a phone in New York. One night—at one in the morning!—I was awakened by Miss Bette Davis, the actress, calling from California to tell me how much she admired something of mine. She had no idea that it was anything later than ten o’clock at night where I was.

“I don’t mind that, but in March, just before I left, the phone rang and a voice said: ‘We are going to castrate you and then kill you.’ All I could say to that was: ‘I think you have the wrong number.’ I’m quite sure he did.…

“When you live in the city, you have to have a phone for making arrangements. And the mail is so terrible there. New York is the richest city in the world and I don’t get my mail until 12 or 1; but here in a little Austrian village I always have it before 9 A.M. So I can take care of everything by correspondence—and, if I have to phone Vienna or Munich, I place a call at the Gasthaus or post office when I’m down there shopping.

“And here my mail reaches me in decent condition. One hears about American ‘know-how,’ but New York mailboxes are so small that they’re clearly designed for people with no friends and no business. Besides, they have little hooks to gaff whatever mail does squeeze in.”

As for television, Auden won’t swallow Marshall McLuhan’s concepts of a “cool medium” and the end of the Gutenberg era. “People still buy books,” says the author of more than two-dozen volumes of poetry. “The one good thing I think McLuhan said is that if TV had been invented earlier, Hitler would not have come to power.”

A purring voice interjects: “Of course, since TV, peace hasn’t broken out all over.” Enter Chester Kallman, bearing a pitcher of Bloody Marys. Even in farmers’ blues on an Austrian hillside, Kallman remains a very heimisch 50-year-old Chester from Brooklyn: a Jewish opera lover who wound up adapting Mozart and Shakespeare and collaborating with “not only the most eloquent and influential but the most impressive poet of his generation” (Auden described by Louis Untermeyer).

Frog-faced, friendly, and fond of an occasional “cutesy-poo” or “my dear,” Kallman is a man who rarely says “hello” or “goodbye”; he just includes you in or sees you out without so much as a nod or a word. He winters in Greece while Auden braves New York or Oxford, but, when they come together in Kirchstetten, the household roles are clearly delineated: Auden shops, sets the table and clears it off; and mixes the evening martinis. Kallman presides over the gardening, cooking, eating, and other drinking.

Whetting the appetite for the lunch to come, Kallman reveals that it will start with a cold cucumber-and-sour-grass soup. The sour grass is home-grown. Kallman refers to it as “spicy sorrel,” but Auden—who is particularly fascinated by German, Yiddish, and Jewish usages—presses him: “You call it something else, Chester, when we don’t have company.”

“Well, Wystan,” replies Kallman, “you can buy it at the Naschmarkt (central market of Vienna) by asking for Schav, which is what we used to call it when we picked it in the back lots of Brooklyn. Of course, I’m no longer sure I’d eat anything that grew in Brooklyn.”

Auden turns to his guest and asks: “Do you know the frightening thing about the dandelions?” The guest, bracing himself for a riddle, confesses that he doesn’t. Auden says: “The dandelions originally were sexual plants. We don’t know when, but in the course of evolution they gave it up. They go on, though, with the same genes.”

It turns out that Auden is a devoted reader of Loren Eiseley and Joseph Wood Krutch. The guest wonders if now is the time to pop the question which too often becomes The Question just by dint of being withheld. Before lunch, however, is too early in ...