![]()

PART I

THE BACKGROUND

dp n="47" folio="36" ?dp n="48" folio="37" ? ![]()

INTRODUCTION

STEVEN M. CAHN

IN 1962 Richard Taylor, already a highly regarded metaphysician and at that time the holder of a chair in philosophy at Brown University, published an article in the prestigious journal The Philosophical Review that astonished its readership. This short, lucid essay with nary a footnote was titled “Fatalism,” and in it Taylor argued that, when suitably connected, six presuppositions widely accepted by contemporary philosophers implied the fatalistic conclusion that we have no more control over future events than we have now over past ones.

Soon after the article’s appearance, a spate of criticisms were offered, all maintaining that Taylor’s argument was unsound but disagreeing as to what mistake he had supposedly made. Taylor wrote several short responses, and as a twenty-one-year-old doctoral student of Taylor’s at Columbia University, where he had moved, I published an extended reply to his critics on which he commented favorably. Several additional articles later appeared with further criticisms of both Taylor’s position and my defense of it.

Reprinted here (unedited except for corrections of misprints and minor stylistic inconsistencies) are the highlights of that colloquy, including Taylor’s original essay, replies by John Turk Saunders, then of San Fernando Valley State College; Peter Makepeace, the non de plume of Bernard Mayo, the British philosopher who edited the journal Analysis and chose not to publish in it under his own name; Bruce Aune, then of the University of Pittsburgh; Raziel Abelson, then of New York University; Richard Sharvy, then of Reed College; and Charles D. Brown, then of Jacksonville University. Also included are Taylor’s answers to his critics as well as my own contribution to the debate.

Was Taylor a fatalist? No. In fact, he thought that two of the six presuppositions, the first and the last, should not be accepted. He believed that while generally propositions are either true or, if not true, then false, this principle does not apply to statements that affirm or deny that a free future action will occur. For example, the assertion that a particular naval commander will order a battle tomorrow is not now true and not now false but will become true or become false with the passage of time.

Taylor recognized that most philosophers disagreed with this account of the relation between time and truth. His strategy was not to argue directly against his opponents but to offer a reductio ad absurdum argument, assuming the truth of his opponents’ position, showing its unacceptable consequences, and thereby demonstrating its falsity.

His readers should have known that he rejected the first and last presuppositions because only five years before, in an article published in the same journal and titled “The Problem of Future Contingencies,” he had elucidated and supported what he took to be Aristotle’s attack on those two claims. Yet that insightful article, with its extensive scholarly apparatus and calm tone, attracted hardly any notice.

So he set out to make his points in a more provocative manner, and succeeded beyond his expectations. Although throughout his career he wrote extensively in defense of free will, and although he viewed positively my 1967 Yale University Press book Fate, Logic, and Time (reissued by Wipf and Stock Publishers), in which I explained his position, to this day Taylor is regarded by many as a fatalist.

While “The Problem of Future Contingencies” (reprinted in the appendix) offers the fullest presentation of his views on these matters, “Fatalism” remains far better known. And no wonder. The article’s style is so accessible, its argument so straightforward, and its conclusion so shocking that the essay continues to pack an enormous punch. Whether any of its critics, including David Foster Wallace, ever found a mistake in its reasoning is for each reader to decide. Regardless, I suspect that, like Zeno’s paradoxes and Anselm’s ontological argument for the existence of God, Taylor’s “Fatalism” will continue to be a source of fascination and puzzlement for countless generations of philosophers.

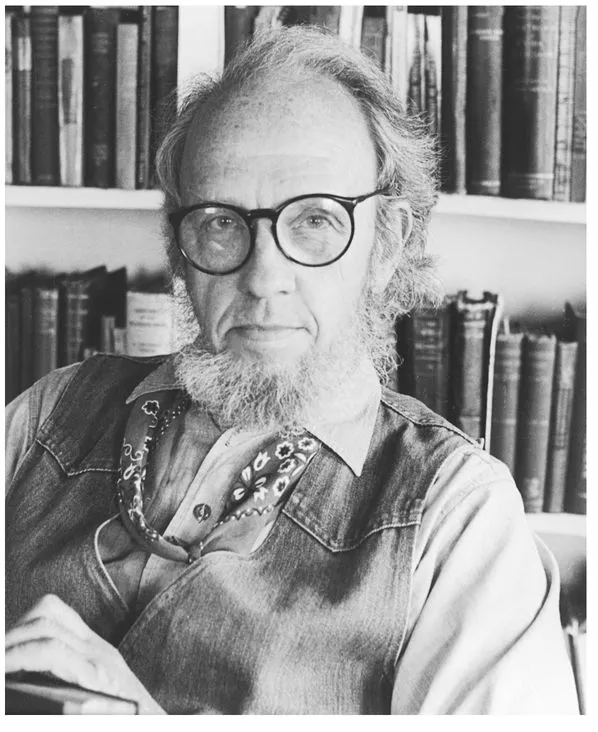

dp n="51" folio="40" ? RICHARD TAYLOR (1919-2003) IN AN UNDATED PHOTOGRAPH. IN ADDITION TO HIS DISTINGUISHED CAREER AS A PHILOSOPHER, HE WAS RENOWNED INTERNATIONALLY FOR HIS KNOWLEDGE OF APICULTURE, THE KEEPING OF BEES.

dp n="52" folio="41" ? ![]()

1

FATALISM *

RICHARD TAYLOR

A FATALIST—IF there is any such—thinks he cannot do anything about the future. He thinks it is not up to him what is going to happen next year, tomorrow, or the very next moment. He thinks that even his own behavior is not in the least within his power, any more than the motions of the heavenly bodies, the events of remote history, or the political developments in China. It would, accordingly, be pointless for him to deliberate about what he is going to do, for a man deliberates only about such things as he believes are within his power to do and to forego, or to affect by his doings and foregoings.

A fatalist, in short, thinks of the future in the manner in which we all think of the past. For we do all believe that it is not up to us what happened last year, yesterday, or even a moment ago, that these things are not within our power, any more than are the motions of the heavens, the events of remote history or of China. And we are not, in fact, ever tempted to deliberate about what we have done and left undone. At best we can speculate about these things, rejoice over them or repent, draw conclusions from such evidence as we have, or perhaps—if we are not fatalists about the future—extract lessons and precepts to apply henceforth. As for what has in fact happened, we must simply take it as given; the possibilities for action, if there are any, do not lie there. We may, indeed, say that some of those past things were once within our power, while they were still future—but this expresses our attitude toward the future, not the past.

There are various ways in which a man might get to thinking in this fatalistic way about the future, but they would be most likely to result from ideas derived from theology or physics. Thus, if God is really all-knowing and all-powerful, then, one might suppose, perhaps he has already arranged for everything to happen just as it is going to happen, and there is nothing left for you or me to do about it. Or, without bringing God into the picture, one might suppose that everything happens in accordance with invariable laws, that whatever happens in the world at any future time is the only thing that can then happen, given that certain other things were happening just before, and that these, in turn, are the only things that can happen at that time, given the total state of the world just before then, and so on, so that again, there is nothing left for us to do about it. True, what we do in the meantime will be a factor in determining how some things finally turn out—but these things that we are going to do will perhaps be only the causal consequences of what will be going on just before we do them, and so on back to a not distant point at which it seems obvious that we have nothing to do with what happens then. Many philosophers, particularly in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, have found this line of thought quite compelling.

I want to show that certain presuppositions made almost universally in contemporary philosophy yield a proof that fatalism is true, without any recourse to theology or physics. If, to be sure, it is assumed that there is an omniscient god, then that assumption can be worked into the argument so as to convey the reasoning more easily to the unphilosophical imagination, but this assumption would add nothing to the force of the argument, and will therefore be omitted here. And similarly, certain views about natural laws could be appended to the argument, perhaps for similar purposes, but they, too, would add nothing to its validity, and will therefore be ignored.

Presuppositions. The only presuppositions we shall need are the six following.

dp n="54" folio="43" ?First, we presuppose that any proposition whatever is either true or, if not true, then false. This is simply the standard interpretation, tertium non datur, of the law of excluded middle, usually symbolized (p v -p), which is generally admitted to be a necessary truth.

Second, we presuppose that, if any state of affairs is sufficient for, though logically unrelated to, the occurrence of some further condition at the same or any other time, then the former cannot occur without the latter occurring also. This is simply the standard manner in which the concept of sufficiency is explicated. Another and perhaps better way of saying the same thing is that, if one state of affairs ensures without logically entailing the occurrence of another, then the former cannot occur without the latter occurring. Ingestion of cyanide, for instance, ensures death under certain familiar circumstances, though the two states of affairs are not logically related.

Third, we presuppose that, if the occurrence of any condition is necessary for, but logically unrelated to, the occurrence of some other condition at the same or any other time, then the latter cannot occur without the former occurring also. This is simply the standard manner in which the concept of a necessary condition is explicated. Another and perhaps better way of saying the same thing is that, if one state of affairs is essential for another, then the latter cannot occur without it. Oxygen, for instance, is essential to (though it does not by itself ensure) the maintenance of human life—though it is not logically impossible that we should live without it.

Fourth, we presuppose that, if one condition or set of conditions is sufficient for (ensures) another, then that other is necessary (essential) for it, and conversely, if one condition or set of conditions is necessary (essential) for another, then that other is sufficient for (ensures) it. This is but a logical consequence of the second and third presuppositions.

Fifth, we presuppose that no agent can perform any given act if there is lacking, at the same or any other time, some condition necessary for the occurrence of that act. This follows, simply from the idea of anything being essential for the accomplishment of something else. I cannot, for example, live without oxygen, or swim five miles without ever having been in water, or read a given page of print without having learned Russian, or win a certain election without having been nominated, and so on.

And sixth, we presuppose that time is not by itself “efficacious”; that is, that the mere passage of time does not augment or diminish the capacities of anything and, in particular, that it does not enhance or decrease an agent’s powers or abilities. This means that if any substance or agent gains or loses powers or abilities over the course of time—such as, for instance, the power of a substance to corrode, or a man to do thirty push-ups, and so on—then such gain or loss is always the result of something other than the mere passage of time.

With these presuppositions before us, we now consider two situations in turn, the relations involved in each of them being identical except for certain temporal ones.

The first situation. We imagine that I am about to open my morning newspaper to glance over the headlines. We assume, further, that conditions are such that only if there was a naval battle yesterday does the newspaper carry a certain kind (shape) of headline—i.e., that such a battle is essential for this kind of headline—whereas if it carries a certain different sort (shape) of headline, this will ensure that there was no such battle. Now, then, I am about to pe...